Gold was discovered on December 1, 1849, by Mormons who were led by Jefferson Hunt to take gold seekers and others to southern California over the Old Spanish Trail. Most wagons left Hunt in southern Utah for a short cut to the gold country—ironically, short-cut survivors took up to two months longer to reach Los Angeles. It wasn’t much of a short cut. Those seven wagons that stayed with Hunt camped on the Old Spanish Trail at Salt Creek, near the present Hwy. 127 and Salt Creek Mountains. Some men rode up the Amargosa Spring wash and found gold. The Los Angeles Star dated May 7, 1851, reported the story.

When Hunt’s group arrived in Rancho Chino, owner Col. Isaac Williams sent out his right hand man Davis to examine the gold site. Ben Wilson, later mayor of Los Angeles and ancestor of General George Patton, fitted out another expedition to check on the Salt Springs site. Both expeditions brought back rich specimens and reported a “whole mountain” of gold bearing ore.

But as was the case of desert mining for years to come, there were obstacles to making desert mines pay off: transportation, distance, food and water, machinery to process the gold so that it would be practical to bring the ore to a smelter. Realistically, in the 1850s, miners still thought that in the Sierra Nevada gold country, gold could still be just picked up.

One explorer went to San Francisco and shared his enthusiasm for the Salt Springs gold. Investors in June, 1850, sponsored another party to investigate. When they came back in July, they formed the Los Angeles Mining Company and made plans to take possession and work the area.

Another of the Los Angeles initial prospectors. Mr. Davis, went to the Sierras to find a supposed Gold Lake. When he returned to Grass Valley, he told Col. Lamb about his trip to “Gold Mountain,” i.e., Salt Springs. Lamb fitted out another exploratory trip, this time led by Davis. Col. Lamb’s group evidently arrived before the Los Angeles company and claimed what he thought were good areas, and sold three-fourth of his interest under the name Desert Mining Company in January 1851. By that spring the two mining companies had three Mexican arrastres (animal powered rock gold crushers) in operation, two for Desert Mining Company and one for Los Angeles Company. The latter company also bought, according to the Star, “a fine engine and machinery on the Amohave (Mojave) River, a little over half way out” —where it became stuck and was temporarily left in the sands of the Mojave River. The assay samples brought into Los Angeles were too few to be conclusive, but varied from 10 cents to many dollars per pound of rock. One of the companies had dug a mine 30’ deep.

Andrew Sublette, famed trapper and mountain man family of brothers, was encouraged to invest in the Desert Mining Company, his great hope to become wealthy. He had became ill gold mining in the Sierras and went to San Jose to recuperate. In a letter to his brother Solomon, March 20, 1851, from Los Angeles, we see his dreams:

“I am concerned with a Company in a gold mine. It is in the rock and very rich. I have been there for six months and will Start out to that place tomorrow [to] take charge and Start some machinery to grind the rock… I have invested all my means (which was but little) in that mine but hope to get it out with interest.”

He was so poor that he borrowed money at 5% to invest and took the job as “chief field man,” (Superintendent). The company did not have enough resources, and President James F. Hibberd tried to obtain additional operating money with more investors and by attaching assessments for the stock owners to pay, or they would forfeit their stocks. For example, on May 7, [1851 ?] the company set an assessment on $2.00 per share. On June 10 it assessed another $1.00 per share. In August, 1851, the Desert Mining Company failed! Sublette declared insolvency. The partnership of B. D. Wilson and A. Packard dissolved.

A new mining company Salt Springs Mining Company, was formed. The new President was Benjamin D. Wilson, Albert Packard was Secretary-Treasurer, also partners in a transportation company. Since Andrew Sublette had no money to invest, he continued as chief field man. The company was running again in November 1851.

Always positive it seems, Sublette praised the mine to the Star, and said that Indians had been troublesome, had stolen tools and ruined machinery, but “The workmen were taking out remarkably rich specimens of quartz: on the whole the news is encouraging.” Sublette sold his holding in St. Louis for $6,000 to pay off bills and invest again in Salt Springs Mining. He wrote to his brother again in March 1852 that he had started mining again with new partners and that prospects were good. He hoped to go back to Missouri and visit again soon. His health has been the best it has been for the last two or three years.

Things were really going well.

But that’s not usual for mining in the Mojave Desert. In the next couple months things were typical for desert mining: Two of his men killed in the Cajon Pass, more Indian difficulties, the 220-mile supply line to Los Angeles, the dwindling supply of money, the calling for stock assessments–all led the Salt Springs Mining Company to try to sell to foreign investors—and that failed, and so did the mining at Salt Springs—for awhile at least.

Sublette, now broke again, went back to his mountain man roots: bear hunting to make some money. He provided some meat for the Los Angeles markets. He was badly wounded, but recovered.

Because of his freight experience and his friendship with Wilson, Sublette received a contract to provide supplies to the new Indian reservation at Ft. Tejon. He went into partnership with James Thompson. They prospered and even leased the La Brea Ranch. According to his biographer, Doyce Blackman Nunis, Jr., Andrew Sublette had quite a resume of occupations: trapper, trader, guide, soldiers, hunter, peace officer, miner—and sometimes with ill-health—he found success as a California Indian Department contractor. Yet, within a few months he was dead at age 40.

Andrew Whitley Sublette’s funeral was in the parlor of the El Dorado Saloon in Los Angeles, and as Major Horace Bell said, “…every gringo in town turned out for the funeral.”

Sublette and his partner, James Thompson, hunted for grizzlies in Malibu Canyon. The two became separated, and when Thompson heard a shot he ran toward it, and found “Sublette locked in hand to hand struggle with the ferocious animal. To one side, partly covered by a cloud of dust stirred up from the contest between man and beast, lay the huddled corpse of the attacker’s mate. Apparently Sublette had slain one of the bears with his rifle, and then before he could reload his weapon, was set upon by another. With knife flashing, his hunting dog, Old Buck, adding his bite to the fray, Andrew finally dispatched his assailant with a mortal thrust. Falling near the crumpled carcass Andrew lay bleeding and dying.”

Thompson got help and took him to the Padilla Building where Dr. Thomas Foster frantically tried to stop the bleeding. The next day Sublette’s trapping, hunting and mining days were over. He was buried at Foothill Cemetery, a dramatic end to a short but glorious life of one of America’s great trappers, Andrew Sublette. Despite his illness, he struggled to the end to make a good living in difficult occupations. His last years added interesting facets to the history of the Mojave Desert.

Salt Springs had another 158 years of history. It continued its up’s and down’s in mining, with scandals where “miners mined the investors,” with a great glory hole, and now this important water hole on the Old Spanish Trail is marked by the BLM with a picnic area, restroom, signs and trails. It is just a hundred yards off Hwy. 127.

Thanks to Emmet for most of this information. I also sourced Andrew Sublette: Rocky Mountain Prince 1813 – 1853, by Doyce Blackman Nunis, Jr, at the Huntington Library.

by Cliff Walker – Mojave River Valley Museum

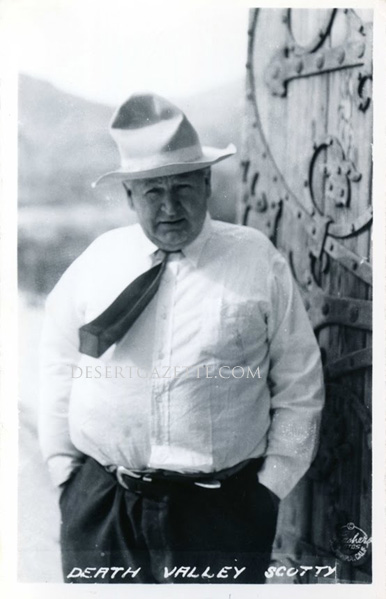

Apparently what the Santa Monica writer didn’t know in 1925 was that Scotty was one of the magnificent cons of the early 20th century. He’d been exposed in 1906 and again in 1912 as a fraud and hoaxer. He relieved numerous gullible investors, including Johnson, of many thousands–invested in nonexistent gold mines. He even did some jail time in 1912. Despite this egregious behavior he remained in Johnson’s affection until Johnson passed in 1948.

Apparently what the Santa Monica writer didn’t know in 1925 was that Scotty was one of the magnificent cons of the early 20th century. He’d been exposed in 1906 and again in 1912 as a fraud and hoaxer. He relieved numerous gullible investors, including Johnson, of many thousands–invested in nonexistent gold mines. He even did some jail time in 1912. Despite this egregious behavior he remained in Johnson’s affection until Johnson passed in 1948.