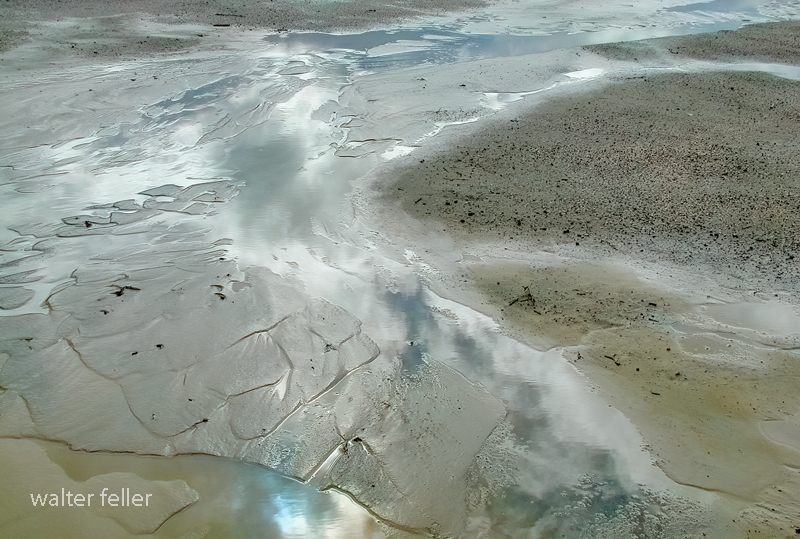

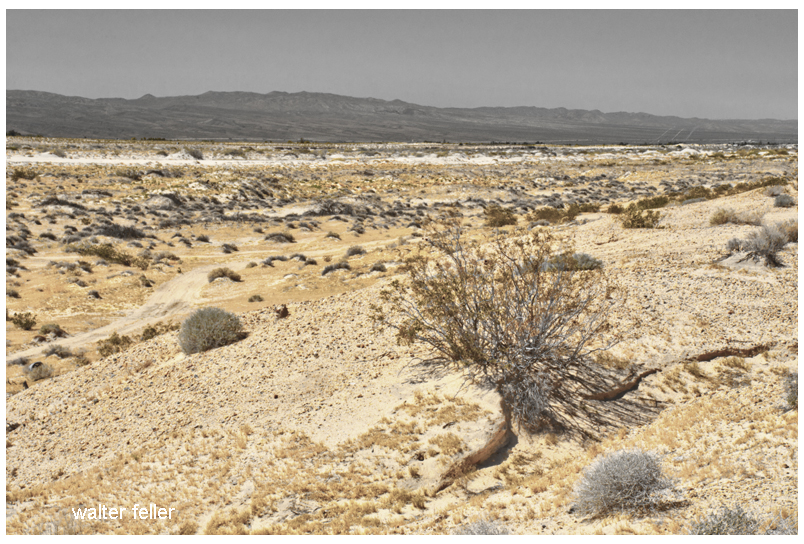

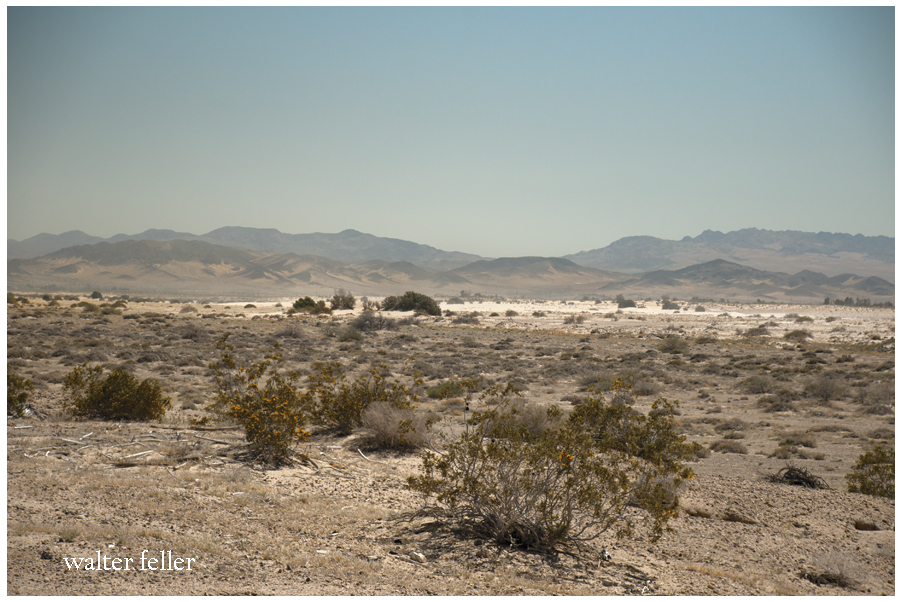

Thin clouds of purest white streaked through the crystalline sky miles above the dune as it glistened and glittered in the morning’s golden sunlight. The ever-present wind swirled out of its invisibility high above grazing the crests of each swell, placing a yellow halo at the crown of each and every rise. Soon, these phenomena broadened and covered everything leeward. Never just one grain but nearly an infinite amount of particles bouncing and flying over the top. The sandscape vibrating and flirting with focus and vision. Wave after wave, all as if it were applauding itself, this audience of at least trillions upon trillions upon trillions of its own. This is the way sand dunes travel and comfort themselves.

There is no apparent grand purpose other than subtle providence, yet, that is grand in itself.

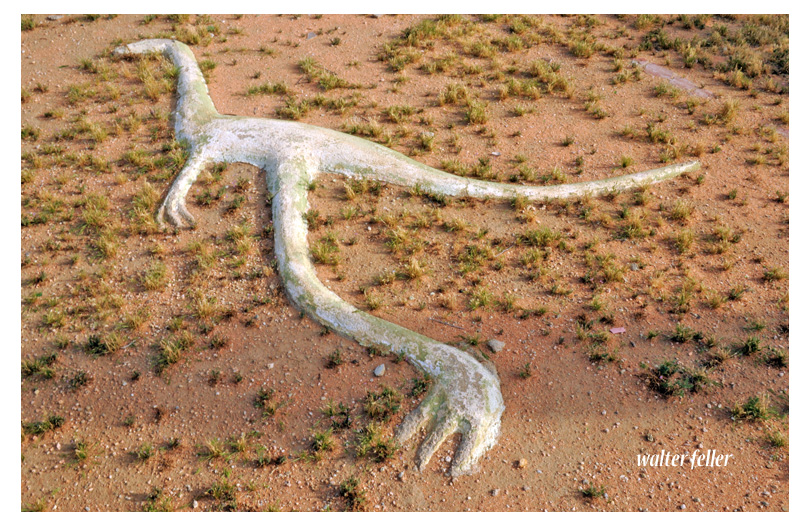

After all the commotion, Bug, the darkling beetle, emerged from its hiding place an inch below the surface. Rat, arrived first, however, and it ate Bug. Then Hawk also swirled out of its invisibility high above in the crystal sky and snatched Rat with bloody talons flying off home to its ravenous brood.

Rat knew he had come to his end, for all rats die as does everything else that lives. Rat was pleased that it was Hawk that would consume him. Coyote or Snake would not honor him with such an aerial showing of the vast world he lived in before he was killed.

END

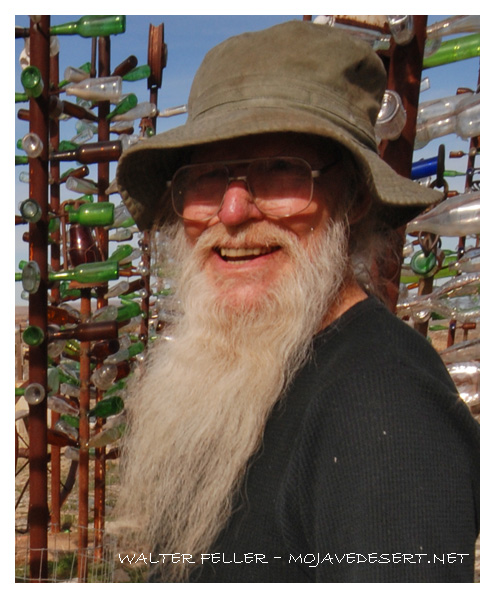

w.feller

END

w.feller