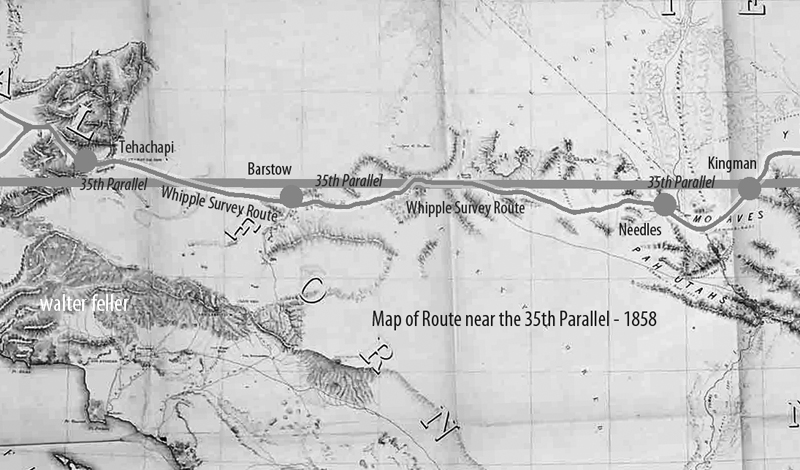

Background: Pacific Railroad Surveys of 1853–1854

In the early 1850s, as the United States expanded westward, national interest grew in finding a viable transcontinental railroad route. Congress appropriated funds in 1853 for multiple surveying expeditions to explore different potential routes across the West.

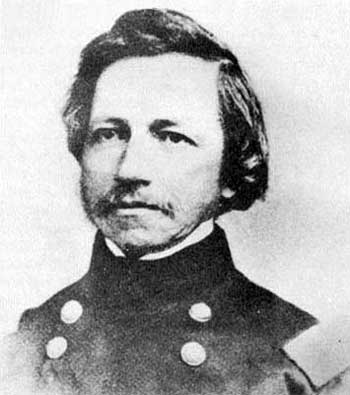

Under the direction of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, the Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers organized surveys along several parallels. Lieutenant Amiel Weeks Whipple, a West Point-trained engineer, was chosen to lead the study near the 35th parallel north, roughly following a westward line from Arkansas to California. The goal was to assess the terrain’s suitability for a railroad, measuring distances and grades, locating mountain passes, and noting the availability of water, timber, fuel, and other resources critical for railway construction. This effort was part of a larger Pacific Railroad Surveys program, which dispatched teams to investigate northern, central, and southern routes for the first transcontinental railroad.

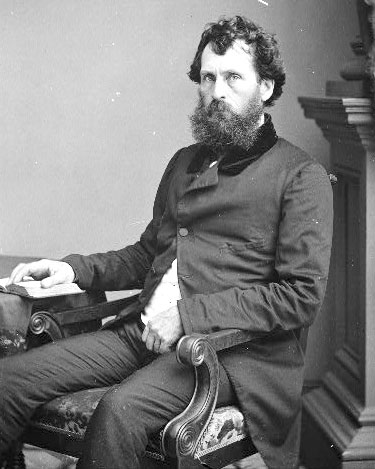

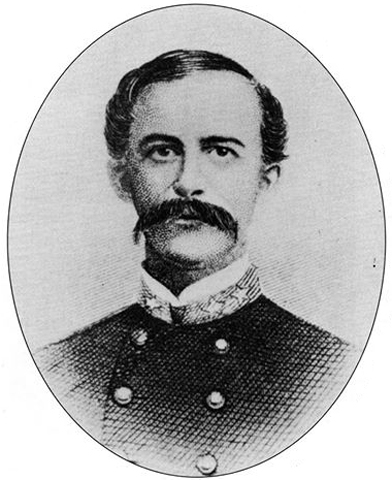

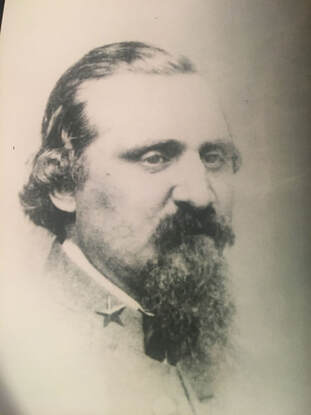

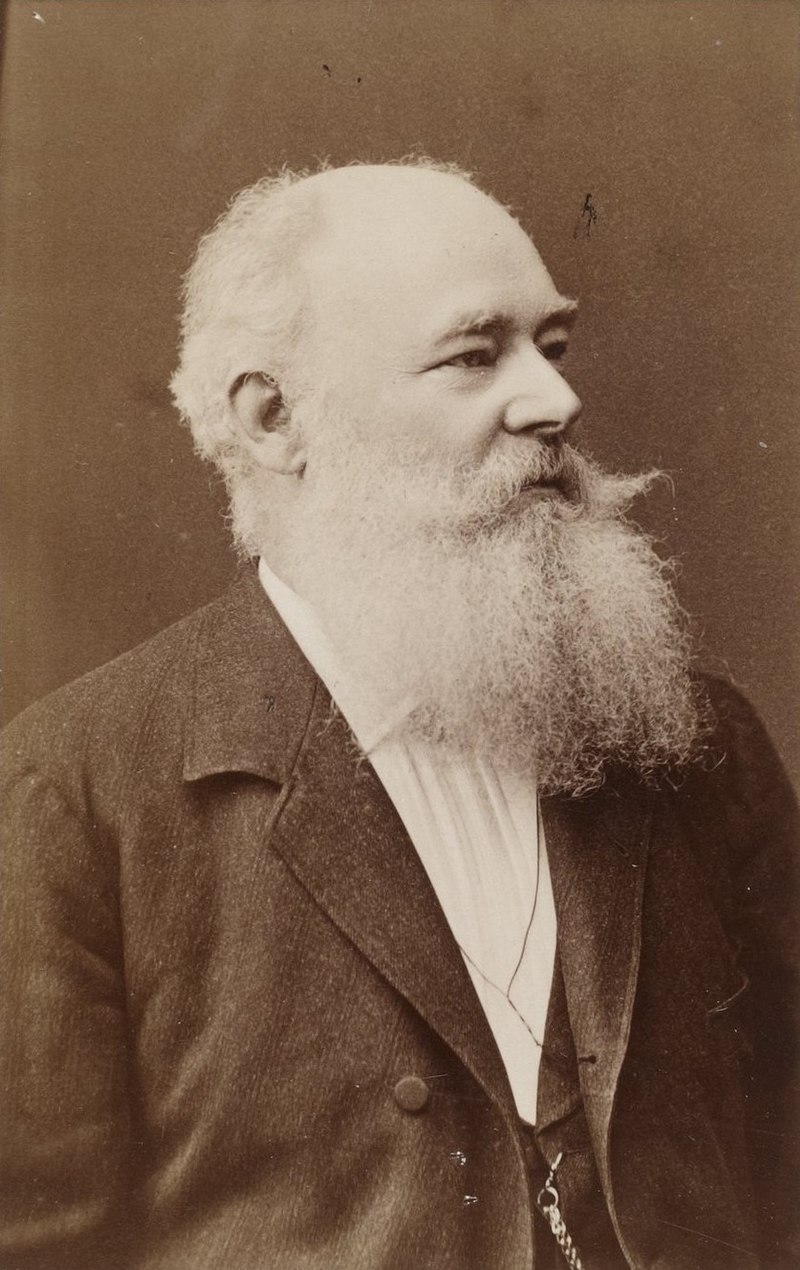

Whipple was already an experienced surveyor. He had worked on the U.S.–Mexico boundary survey after the Mexican–American War and had a reputation for scientific thoroughness. For the railroad survey, Whipple assembled a multidisciplinary team of about seventy men, including Army soldiers for security, teamsters to handle the wagons, and a number of scientists and specialists. The Smithsonian Institution helped select many of the expedition’s experts, reflecting the survey’s dual nature as both a route reconnaissance and a scientific exploration of the largely unmapped Southwest. Notable members of Whipple’s party included John Milton Bigelow, a physician and botanist; Jules Marcou, a geologist from France; and Balduin Möllhausen, a German artist and naturalist who had the backing of famed explorer Alexander von Humboldt. Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives, a young Army engineer, served as Whipple’s second-in-command and led a sub-party during the journey. The team’s diverse expertise meant that, in addition to plotting a railroad route, they would document the region’s flora, fauna, geology, and ethnography in unprecedented detail.

Journey from Fort Smith to New Mexico Territory

Whipple’s expedition officially commenced in mid-July 1853 at Fort Smith, Arkansas, then a border outpost to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The caravan – a long train of wagons and pack animals – set westward from Fort Smith on July 15, 1853. The team initially followed established trails where possible: they crossed the Poteau River into Indian Territory and proceeded along rough wagon roads just south of the Canadian River. This path had been traversed a few years earlier by expeditions such as Captain Randolph Marcy’s 1849 wagon road survey to Santa Fe. Even so, much of the region remained sparsely charted. The landscape of eastern Oklahoma was a patchwork of settlements belonging to relocated Native American nations (Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, among others). As they traveled through these inhabited areas, Whipple often sought advice and guides from local Native people. The party moved steadily but cautiously, averaging only a few dozen miles per day due to the heavy wagons and the need to survey as they went.

Throughout the Indian Territory, Whipple was struck by the relative fertility and land resources. In contrast to earlier notions of the Southern Plains as part of the “Great American Desert,” Whipple described parts of what is now Oklahoma in encouraging terms. His team noted ample timber stands in regions like the Cross Timbers and discovered occurrences of coal, both assets for any future railroad. They found the prairie soils suitable for agriculture, observing that the area could yield abundant crops with sufficient water. Wildlife was surprisingly scarce along their route at first (likely due to overhunting and the presence of settlements). Still, as the expedition progressed into less populated areas, they encountered more game, including herds of bison and the occasional bear on the plains. The surveyors also recorded observations on the Native tribes they met. Whipple, with an ethnographer’s eye, collected information on indigenous languages and customs. He and his colleagues compiled vocabularies of various Native languages and noted the social conditions of the tribes, many of whom had been relocated to the Territory. The hospitality of local Native leaders helped the party traverse the region; in return, Whipple’s reports portrayed the tribes in a largely favorable light and even noted their openness to the idea of a future railroad bringing new opportunities.

By late summer, the expedition reached the Texas Panhandle, entering an environment of open high prairie. Here, the going became more challenging – the trails were faint, water sources more intermittent, and the heat and dryness more intense. In early September, the party was trekking across the flat expanse known as the Llano Estacado (Staked Plain) in what is now the Texas–New Mexico border area. Despite the hardships of travel across these arid plains, Whipple remained optimistic about the route’s potential. He reported that much of the rolling prairie appeared well-suited for laying track, with gentle grades and few significant barriers. Occasional hazards did arise: at one point, massive prairie fires swept across the dry grasslands, forcing the survey team to move camp to avoid the flames hurriedly. Nevertheless, the expedition pressed onward without major incident by carefully timing their marches between water holes and taking guidance from seasoned frontier scouts.

In early October 1853, Whipple’s party reached Albuquerque in the New Mexico Territory. This was a significant milestone and a chance to regroup. Albuquerque had been an outpost on the old Santa Fe Trail, providing a place to resupply and rest after the long plains crossing. Here, the expedition was joined by Lieutenant Ives’s detachment, which had taken a slightly different approach route. Ives and a small group had traveled separately via a southern path, moving from the Gulf of Mexico through Texas (through San Antonio and El Paso) and northward up the Rio Grande to rendezvous with Whipple. The combined expedition, now fully assembled in Albuquerque, prepared to tackle the most demanding portion of the journey: the remote deserts and mountains between New Mexico and California. They hired an experienced guide, Antoine Leroux, a frontiersman familiar with western trails, to assist in navigating the unknown terrain ahead. As autumn turned to winter, Whipple’s caravan departed Albuquerque, heading west into increasingly rugged country.

Across Arizona and the Mojave Desert to California

Leaving the relative civilization of the Rio Grande valley, Whipple’s survey entered what is now Arizona – a land largely unmapped by Americans at that time. The expedition first passed through the lands of the Zuni Pueblo, one of the Indigenous villages in western New Mexico. Whipple was very interested in the pueblo cultures; he paused to exchange greetings and study their way of life briefly, even sketching and describing Zuni architecture and traditions for his report. The party struck out from Zuni across northeastern Arizona, traversing the Painted Desert region. They aimed for the Little Colorado River, which they reached by following ancient Native trails. This stretch was difficult: water and grass were scarce, and the winter cold began to set in. The surveyors likely encountered patches of snow as they ascended in elevation. Still, the group persevered, mapping the terrain carefully. They made note of volcanic formations and other geologic curiosities as they approached the lofty San Francisco Mountains (the San Francisco Peaks near modern Flagstaff, Arizona).

Guided by Antoine Leroux, the expedition found a pass through the San Francisco Mountains and descended into the basin of the Colorado River. By January 1854, they were in some of the most remote territory of the Southwest – a stark land of canyons and plateaus. Here, two Mohave Native American guides joined the party and proved invaluable. The Mohave people inhabited the river valley and deserts around the lower Colorado, and they knew the best routes through the arid labyrinth ahead. Under the guidance of these local scouts, Whipple’s team followed a path down a tributary called Bill Williams Fork to reach the Colorado River itself near the boundary of modern Arizona and California.

Crossing the Colorado River in the winter of 1854 was one of the expedition’s most significant challenges. The river was swift and cold, and the expedition had to build rafts or use whatever boats they could improvise to ferry men, animals, and equipment across. This crossing proved disastrous – strong currents nearly swept away some of the party’s wagons and scientific collections. A makeshift raft capsized at one point, and several precious items (instruments and specimen jars) were lost to the muddy waters. Fortunately, no lives were lost, and Whipple managed to get his entire command safely to the western bank after considerable effort and delay. By February 7, 1854, the surveyors stood in California, having conquered the last significant natural barrier on their route.

Now the task remained to cross the vast Mojave Desert of southeastern California and reach the settled areas near the Pacific coast. The Mojave presented different obstacles: arid expanses, occasional sand dunes, and long stretches with no reliable water aside from a few springs. Still accompanied by their Mohave guides, Whipple’s party navigated along established Native trails that connected waterholes across the desert. They moved generally northwest from Colorado, eventually picking up the path of the old Mojave Road (a route used by Native Americans and the early Spanish travelers to California). This trail led toward the Mojave River, a critical lifeline in the desert. Following the Mojave River upstream (southwestward), the expedition could find water and grass for their stock at intermittent stream bends and oases.

Traveling along the Mojave River, Whipple noted signs of earlier travelers – evidence that this route had been used by Spanish missionaries, American fur trappers, and emigrant wagon parties in years past. They were approaching where the Mojave Road merged with the Old Spanish Trail and the newer Southern California wagon roads. The terrain gradually changed: dry lakes and creosote flats gave way to the higher elevations of the California Coast Range. The expedition’s final hurdle was to cross the San Bernardino Mountains via the Cajon Pass, the same pass used by traders and settlers to enter southern California. Cajon Pass was a natural mountain pass between the Mojave Desert and the coastal valleys. Whipple’s survey assessed this pass carefully, measuring its grade and width, and found it to be a favorable corridor for a railroad line. He reported that Cajon Pass, already well-traveled by wagons, could be engineered for locomotives without extraordinary difficulty – a significant affirmation, since this gap was the gateway to Los Angeles.

After emerging from Cajon Pass, the weary expedition descended into the green fields of southern California. They passed through the outskirts of San Bernardino, a young Mormon-founded community, and finally reached Los Angeles on March 20, 1854. This completed an epic journey of roughly 1,800 miles from the Mississippi River to the Pacific coast. Whipple’s team had spent about eight months on the trail, enduring extreme weather, rugged terrain, and occasional threats (from the environment more so than from people – indeed, relations with Native tribes along the way had been largely peaceful and cooperative). The triumphant arrival in Los Angeles marked the conclusion of the field survey. However, in many ways, Whipple’s work was just beginning: he now had to compile his findings and analysis for the government, recommending whether this 35th parallel route was suitable for a transcontinental railroad.

Scientific and Cultural Observations

Beyond its purely geographic accomplishments, the Whipple expedition made significant scientific and cultural contributions. It was, by design, a traveling research laboratory. The team’s specialists collected volumes of data and specimens throughout the trek. Botanist John Bigelow gathered hundreds of plant samples, discovering species new to science (many western plants would later be named in honor of Bigelow). Geologist Jules Marcou studied rock formations along the route, producing one of the first geological transects of the American Southwest – identifying coal seams and mineral deposits, and noting the volcanic origins of landscapes like the San Francisco Peaks. Topographical drawings and paintings by Balduin Möllhausen, the expedition artist, provided eastern audiences with their first realistic views of wonders such as pueblo villages, broad prairie vistas, and desert mountain ranges. Möllhausen also kept a personal journal describing daily life on the trail, which, along with the diary of assistant surveyor John P. Sherburne, offers vivid insights into the expedition’s experiences (both of these journals were later published and are valuable historical sources).

Lieutenant Whipple was intensely interested in ethnography (the study of cultures). As the expedition passed through regions inhabited by diverse peoples – from the settled Choctaw and Chickasaw farms in Indian Territory to the semi-nomadic Apache bands in New Mexico, the Pueblo villages, and the Mohave and Yavapai groups near the Colorado – Whipple took the time to observe and document their ways of life. He recorded information on tribal governance, agriculture, and daily customs. One notable effort was the compilation of vocabularies: Whipple’s report included comparative word lists for numerous Native languages encountered on the journey, preserving linguistic data that might have otherwise been lost. He was generally respectful in his descriptions, often noting the hospitality and helpfulness the survey party received. For instance, the Zuni and Mohave guides were crucial to the expedition’s success, and Whipple acknowledged their vital role in navigating the rugged country.

The scientific observations were not just academic; they directly tied into evaluating the railroad route’s feasibility. Whipple’s team cataloged where good timber stands grew (necessary for supplying wood for construction and fuel), where water was available year-round, and the locations of coal, iron, or other minerals that might support a railroad economy. In Oklahoma and New Mexico, they identified river valleys and mountain passes that could accommodate tracks with gentle gradients. In the drier sections of the route, they noted stretches that might require constructing wells or aqueducts to supply locomotives with water. The data collected on weather and climate led Whipple to an interesting conclusion: the 35th parallel route, he believed, had a climate “favored by precipitation” compared to some more northerly routes. In other words, he thought this middle-southern route received enough rainfall. He had enough perennial streams to sustain a railroad, without the extreme snowfalls that plagued routes farther north and without the absolute aridity of the far southern deserts. His final report reflected this climatic optimism, emphasizing the agricultural and settlement potential of the lands along the 35th parallel line.

Results and Legacy of the Expedition

Upon reaching California, Whipple and his colleagues turned to organizing their notes, maps, and collections. Over the next year, they prepared a comprehensive report for the War Department. Lieutenant Whipple authored the narrative of the journey and the analysis of the route’s suitability for a railroad. He highlighted that the expedition had identified a practicable rail corridor. There were only a few significant obstacles (notably the crossings of the Pecos and Rio Grande rivers and the passage through Cajon Pass), and even those could be overcome with engineering effort. Whipple’s engineer, A. H. Campbell, compared these challenges to building railroads in the Appalachians back east, implying that nothing in the West was insurmountable by modern (1850s) engineering standards. In Whipple’s estimation, the 35th parallel route offered an attractive balance: it was shorter than the far-southern route through Texas, avoided the highest peaks and snows of the central Rockies, and ran through regions that appeared fertile enough to populate and economically develop.

The U.S. government published the expedition’s official findings as part of a monumental series titled “Reports of Explorations and Surveys to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.” Whipple’s report was contained in Volume III of the Pacific Railroad Survey Reports (1856), including his detailed narrative, maps, and journey illustrations. An accompanying Volume IV (1856) contained the scientific appendices: reports on geology, botany, zoology, and a significant essay by Whipple on the Native American tribes of the Southwest. These volumes were richly illustrated with lithographs based on Möllhausen’s sketches – images that introduced Americans to scenes like a Plains Indian encampment, a Pueblo village under the cliffs, and the majestic profiles of western mountain ranges. The reports were technical documents and essential works of natural science and anthropology for their time.

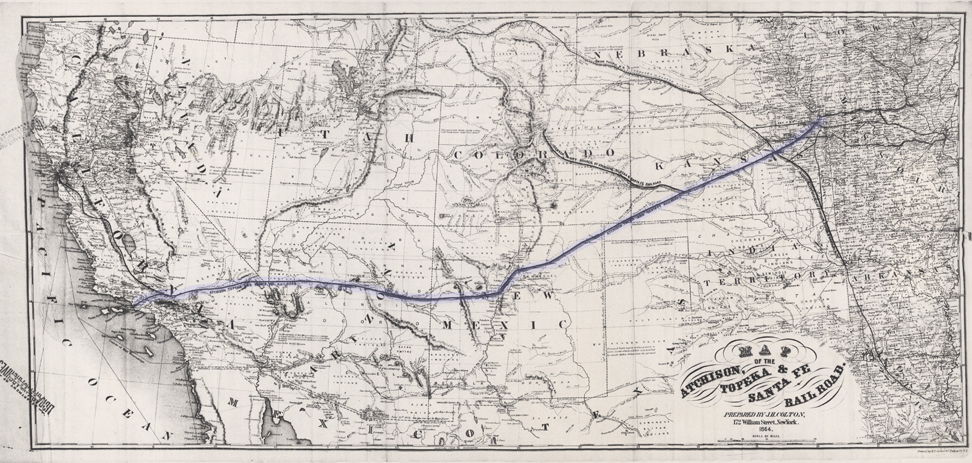

Despite Whipple’s strong recommendation of the 35th parallel route, the decision on a transcontinental railroad was ultimately delayed by political conflict. In the 1850s, Congress remained deadlocked between Northern and Southern factions, each promoting different routes. No single route was chosen before the outbreak of the Civil War. Whipple’s careful survey, unfortunately, did not immediately lead to the construction of a railroad along his line. Indeed, when the first transcontinental railroad was finally built in the 1860s, it followed a more central route (far north of Whipple’s line) to connect Omaha with Sacramento. However, Whipple’s work was not in vain. His survey proved that a railroad could traverse the Southwest and helped identify the best passageways through a once-mysterious region. In the decades after the Civil War, railroad companies did turn to the 35th parallel corridor: the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (later part of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway) built westward along much of Whipple’s path through New Mexico and Arizona. By the late nineteenth century, a transcontinental railway line was completed along the 35th parallel, validating Whipple’s original vision by providing a direct rail link to Los Angeles through the Mojave Desert.

The Whipple expedition also left a lasting legacy in science and exploration. The enormous collection of plant and animal specimens sent back east enriched American museums and led to the description of new species. The detailed maps produced by Whipple’s cartographers became base maps for the Southwest, used by future travelers, the military, and settlers. His ethnographic notes provided scholars with early documentation of Native cultures in regions that would soon experience dramatic change. Additionally, members of Whipple’s team went on to notable careers: Joseph Ives later led his famous expedition to explore the Colorado River in 1857; Balduin Möllhausen published his illustrated diaries and became known in Europe as an author on the American frontier; and Amiel Whipple himself continued his Army service, ultimately becoming a Union general in the Civil War (tragically, he was mortally wounded at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863).

In summary, Lt. Amiel W. Whipple’s 1853–1854 survey along the 35th parallel was among the most successful and influential Pacific Railroad Surveys. It combined meticulous route reconnaissance with scientific inquiry, painting a comprehensive picture of the lands between Fort Smith and Los Angeles. Whipple demonstrated that a railroad through the Southern Plains and Southwest was feasible and revealed the economic promise of that region. His expedition’s findings, published in the Pacific Railroad Survey volumes and subsequent works, helped guide the nation’s understanding of the Southwest and paved the way—literally and figuratively—for future railroads and settlements along his route.

Sources

- Reports of Explorations and Surveys… Volume III (1856). Route near the Thirty-Fifth Parallel, under the command of Lt. A. W. Whipple. Washington: War Department, 1856. (Official Pacific Railroad Survey report with Whipple’s narrative, maps, and illustrations.)

- Reports of Explorations and Surveys… Volume IV (1856). Washington: War Department, 1856. (Contains Whipple expedition’s scientific reports on geology, botany, zoology, and appendices on Native American tribes.)

- Foreman, Grant (ed.). A Pathfinder in the Southwest: The Itinerary of Lieutenant A. W. Whipple during his Explorations for a Railway Route from Fort Smith to Los Angeles in 1853 and 1854. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1941.

- Gordon, M. M. (ed.). Through Indian Country to California: John P. Sherburne’s Diary of the Whipple Expedition, 1853–1854. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988.

- Conrad, David E. “The Whipple Expedition in Arizona, 1853–1854.” Arizona and the West 11, no. 2 (1969): 147–178.

- Goetzmann, William H. Army Exploration in the American West, 1803–1863. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1959.