by A. R. Clifton. A. M. – 1917

One of the most interesting studies of practical Socialism in Southern California is the history of the communistic colony, Llano del Rio, established in the Antelope Valley in 1914. This colony was founded by Job Harriman, a prominent Socialist of this State, and a company of associates who, like himself, were disappointed at the results accomplished by the Socialist party. In their opinion, tangible and measurable benefits to the cause would follow a practical demonstration of the principles of Socialism through community production and distribution, which could not be expected in any other way. In order to test the plan, this group of men began looking for suitable land upon which they could establish a cooperative settlement. After considering various propositions in Oregon, Nevada, and Arizona, as well as California, it was decided, everything considered, that a tract in the southern part of the Antelope Valley offered the largest advantages, so negotiations were quietly begun for obtaining control of the land and the water.

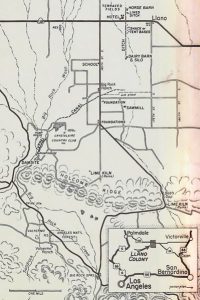

The site was located between Palmdale and Victorville — about twenty miles from Palmdale and thirty miles from Victorville, and about fifty miles northeast of ‘Los Angeles. Company literature states : “The property lies for the most part between Rock Creek and Mescal Creek, on the plain below, and running to the base of the mountains that form a magnificent watershed and which are snow capped for several months of the year”.1

It is part of the Angeles Forest Reserve and is in township 5 north, ranges 8, 9 and 10 west, San Bernardino meridian. The company holdings consisted of ten thousand acres when the colony occupied the tract, much of which was in the wild’ state, covered with chaparral, sage, greasewood, yuccas and junipers. The soil is largely decomposed granite, feldspar and lime of unknown depth. It contains sulfides and oxides of iron, potash, soda, carbonate of lime and magnesia. The essentials of plant life are found there in reasonable abundance.

The lay of the land is ideal ; comparatively little is rough and that part is the foothill section, a portion of which was used for reservoir sites, the fish hatcheries, lime! kilns and stone quarries. From here the land slopes gently, making irrigation an easy matter.

The lay of the land is ideal ; comparatively little is rough and that part is the foothill section, a portion of which was used for reservoir sites, the fish hatcheries, lime! kilns and stone quarries. From here the land slopes gently, making irrigation an easy matter.

The water supply during the development period of the colony promised to be sufficient to meet all needs, present and future, if properly conserved and distributed. The exclusive right of the flow from Mescal Creek, Jackson’s Lake, and Boulder Creek had been secured and practically all of the flow from Big Rock Creek, through the control of the Big Rock irrigation district. Jackson’s Lake alone in the driest season yields one hundred and fifty miner’s inches and could be increased through the use of reservoirs. There are four good reservoir sites on the property with a total capacity of between thirty thousand and forty thousand acre feet.

The chief engineer in his report of 1915 says: “The area of watersheds adjoining these lands is approximately eighty square miles, which, with the usual forty inches of rainfall per annum, should yield about seventy thousand acre feet of water that could be used if it could all be saved — enough water, with the probable character of crops, to maintain forty thousand to fifty thousand acres of land under cultivation. Enough is known to assure an irrigated area of ten thousand acres or more of any crops, enough to support a population of five thousand souls and have a surplus of product for the open market”.2

The fall of water supplying the colony seemed sufficient, after the installation of power plants, to provide all the electricity for both light and power for many years to come. The water of Jackson’s Lake alone could have been distributed and directed so that there would be three separate drops of five hundred feet each. At the other end of the tract the proper development of the flow of Big Boulder Creek would have provided one of the most valuable power sites in the State of California, and the natural formation of foothill and valley would have made the development work comparatively inexpensive. A dam about two hundred feet in length and one hundred feet high, constructed between the hills on either side of the creek, would have flooded two hundred acres, making an immense amount of water available for irrigation as well as power for the generation of electricity.

The Llano del Rio Company had deeds to over two thousand acres of land, held tax titles to three thousand five hundred acres more, and through members of the colony had control of, three thousand five hundred acres additional, which made a tract of over nine thousand acres in all. Even this acreage did not satisfy the ambitions of the colonists. They planned to secure extensive additions — even up to thirty thousand acres, the amount of land in this irrigation district.

The cultivated land during the season of 1917 consisted of about two thousand acres, distributed as follows: alfalfa, four hundred acres ; orchard, one hundred twenty acres ; nursery, one hundred ; garden, one hundred twenty ; corn, two hundred ; and the balance in grain and general farm crops.

Those in authority at the colony maintained that it was possible for the members to devote their energy to the raising of a large variety as well as large quantities of products. The Vice-President informed me that peas, beans, potatoes, melons and all vegetables grew there abundantly; that of the fruits they would soon be producing pears, apples, peaches, plums, cherries, apricots, olives, and figs. These with the products of the dairy, the chicken yards, the rabbitry, the hog ranch and apiary would, according to the plan, not only feed the people of the colony but would enable them to buy in the quantities needed the things they could not produce.

Those in authority at the colony maintained that it was possible for the members to devote their energy to the raising of a large variety as well as large quantities of products. The Vice-President informed me that peas, beans, potatoes, melons and all vegetables grew there abundantly; that of the fruits they would soon be producing pears, apples, peaches, plums, cherries, apricots, olives, and figs. These with the products of the dairy, the chicken yards, the rabbitry, the hog ranch and apiary would, according to the plan, not only feed the people of the colony but would enable them to buy in the quantities needed the things they could not produce.

After four weeks of existence, the ninth of May, 1914, closed with five members. They had but a few tools with which to begin work, four horses, one cow and sixteen hogs.

Considering so small a beginning, the growth for the first three years was rather notable. There were, August 1, 1917, about one thousand members with nine hundred residents in the colony. There were one hundred head of horses, one hundred and twenty-five Jersey and Holstein cows and one hundred head of young stock, three hundred hogs, several thousand rabbits and chickens, six hundred eighty stands of bees, one hundred fifty turkeys, thirty-two goats, three trucks, twenty wagons, seven automobiles, a traction engine, a caterpillar engine, leveller, concrete mixer and pipe moulds for the making of cement pipes for the irrigation system, drags, and various other pieces of heavy machinery for clearing and preparing the land for planting on a large scale.

The buildings were largely of a temporary character, due partly to the fact that the site of the residence section was to be changed to ground a little higher, more protected from the wind and nearer the source of water most desirable for domestic purposes. There were tents and adobe houses enough, with the rooms in the club house, to take care of the nine hundred people in Llano at that time, and more were being put up as needed. They had a planing and sash and door mill of sufficient capacity to do all the sawing and milling work for the building operations.

The hen coops and rabbitry were modern in construction and very commodious, and it was intended to increase the capacity rapidly. The cattle barn was constructed of cobblestone, with tin roof, a great improvement over the cheaply constructed barn which I saw on my first visit to the colony in 1915. A fine concrete silo of three hundred ton capacity had recently been constructed, and the plans were well under way for a well-equipped dairy.

The office was small, but it answered the purpose very well. The Llano post office was housed in this building.

The most used and the most popular structure of the colony was the Club House. It consisted of a building fifty by one hundred and fifty feet, containing rooms for single men, the commissary department, the club kitchen and dining room, the barber shop, the colony boarded in the club dirting room. They were charged seventy-five cents a clay for their meals. This room, fifty by sixty feet, was used as the general audience room of the colony. It was here the assembly had its official meeting and where lectures, musical entertainments and parties were held.

The machinery for a steam laundry had been installed, which greatly lightened the housework. A lime kiln of one hundred fifty barrels capacity daily was in operation. An ice plant, a tannery and a shoe factory were to have been established if the plans for the colony had matured.

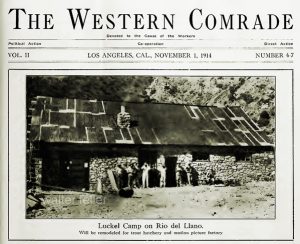

A printing plant had been established which, though of limited capacity, turned out a large amount of work. It was here the “Western Comrade”, a monthly magazine of thirty-two pages, the “Llano Colonist”, a weekly, and the pamphlets of the colony were published. This office had become the chief California center for the publication and dissemination of socialistic literature.

A well-equipped canning plant which was a valuable asset to the company activities had been installed. Both vegetables and fruits were preserved for the season when they could not be procured fresh. Quantities of fruit were made available by exchanging labor for it. Cleaning, dyeing, and soap-making added their contributions to the Llano industries. The list would not be complete without a mention of the rug-making department. Most excellent work was done — much better than one would think possible in the meager quarters provided. Rugs of beautiful design and good value were produced.

The homes of the people, as would be expected in an enterprise of this kind, were crude — tents and adobe of sun-dried brick, of one or two rooms. They were meagerly furnished for the most part, but sanitary; and no one seemed to be the worse for the pioneer experience. The home planned for the future, however, — the one which according to the contract of the company it was under obligation to build for all members of this cooperative plan, — was to be much more comfortably appointed, and is thus described in the company literature: “The house will be built around a patio or court, turning a blank wall towards the neighbor, against which he in turn constructs his house. Then you look across your own garden at your own windows and neither hear nor see your neighbor, who retires behind a soundproof wall.

When in your garden you can lounge or work at your ease, and if you turn your little children out of doors they will never be out of sight, no matter what room in the house you may be in. There is a living room twenty by twenty-eight feet, a sun-parlor dining room thirty-five by fourteen feet, two bedrooms ten and one- half by twelve and one-half feet, with a bathroom between them. Upstairs there is a flat roof, separated from your neighbor’s by an eight-foot wall with eaves, with two dressing rooms and space for eight beds arranged two by two in separate recesses. These beds only occupy part of the roof at any time, but they can be folded back against the wall, leaving the roof free. So, if desired, twelve people can be accommodated downstairs and up, without any crowding”.8

The proposed construction of these homes indicated a complete system of water works and a sewerage system.

All the products of the colony passed through the commissary department. Here they were weighed, sorted and placed on the market to members of the colony at a price as near cost “as practicable”. It was also agreed by contract that all clothing was to be purchased from the company. Both food and clothing were very plain. All surplus funds were needed in the development work, hence little was left for anything but the bare necessities.

The work of opening up a desert ranch, — planting, sowing, irrigating, harvesting, building and planning, — is strenuous, but there seemed to be a willingness on the part of practically everyone to bear his share of the burdens. Eight hours were the regular day’s work. There were those, however, who worked longer and who were willing to do it, for as several expressed it to me, “We are working for ourselves now. No capitalist who has no interest in us further than that we can increase his wealth, gets the benefit of our extra work. It belongs to us”. There were some, however, who seemed to have no particular desire to put in extra time for the benefit of the community interests.

The work of opening up a desert ranch, — planting, sowing, irrigating, harvesting, building and planning, — is strenuous, but there seemed to be a willingness on the part of practically everyone to bear his share of the burdens. Eight hours were the regular day’s work. There were those, however, who worked longer and who were willing to do it, for as several expressed it to me, “We are working for ourselves now. No capitalist who has no interest in us further than that we can increase his wealth, gets the benefit of our extra work. It belongs to us”. There were some, however, who seemed to have no particular desire to put in extra time for the benefit of the community interests.

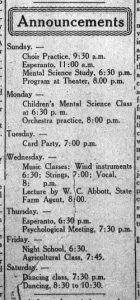

I was very much interested in the social life and amusements of Llano. In view of the social needs of the community the club house was constructed, which became the natural center of the people. In the large assembly hall, those musically inclined often gathered around the piano to sing, while the rest listened or visited. Here each Saturday night the young people — and many of the older folks, too — gathered for a dance. This was occasionally repeated during the week. One evening when I was present the entertainment consisted of a “suffragette ball”. The girls wore the clothes of their fathers or brothers and the boys borrowed from their sisters or other female members of their families. The whole colony seemed to be present. Those who did not dance appeared happy in the enjoyment of those who did. A jolly good fellowship was everywhere present. The Tuesday night children’s dance was one of the enjoyable social customs of the colony. The young people from the ages of six to fifteen had the floor exclusively to themselves. They were taught, not only the dance steps but the courtesies which belong to the dance floor, in order that they might acquire grace and poise, learn the forms and social customs which characterizes the pleasure and exhilaration which comes from this activity.

Each Sunday evening there was an entertainment of a literary and musical nature. The program consisted of talks or lectures by members or visitors, readings, recitations, home talent plays, concerts or musical numbers by the orchestra, band, the mandolin or guitar organizations, or by individuals or groups who could furnish vocal music. These programs were interesting and instructive and were of greater merit than one not acquainted with the colony conditions would expect to find.

The young men had football, baseball, basket ball, and tennis teams. They had pool and billiard tables and also enjoyed checkers, dominos and chess.

The plans for the new city included tennis courts, running tracks, football grounds, baseball diamonds, golf links and well- equipped playgrounds for children.

There was a woman’s reading circle and an Esperanto club. Notices of the meetings were posted prominently on the bulletin boards of the club house.

Recreation and amusements were given a prominent place in the life of the colonists at Llano. It was their policy to lighten the cares of life by mental and physical activities which afford opportunity for relaxation of mind and body and give zest to the daily duties.

“What would be done with a man who became incapacitated through old age, accident or sickness and was unable to earn anything” ? was a question often asked by colonists, until it was answered at a meeting of the Assembly, July 20, 1915. It was decided by a unanimous vote that all such persons should be cared for by the colony the rest of their lives. While this action might have been rescinded later on, it at least indicated at that time a good degree of “social solidarity”. The policy pursued by the colony in several cases where members were unable to carry their part of the community load proved that the resolution passed at the meeting referred to was not a matter of theory only, but was a part of their practice. They did in this matter just what they promised they would do.

No provision was made in the colony for the building of churches. The company had no intention of constructing any church edifices. There were many denominations represented at Llano, and members held religious meetings in their homes, if they so desired. Later it was expected that halls and auditoriums would be built which could be used for church as well as other purposes. One of the leaders of the colony remarked that they cared little for religion, as such, but were very much interested in every-day Christianity, the proper and just relationship of man to man.

Substantial plans had been made for a good school system m Llano. At the end of the school year, June 30, 1917, there were one hundred twenty-five pupils enrolled. The courses ranged from kindergarten to the second year in the high school, and the work was under the supervision of the County Superintendent. The County course of study formed the basis of the work, and State and County support was received.

Besides this department of education there was maintained what was known as the “Industrial School”, where no County or State requirements were adhered to and for which no County or State support was expected. This school was established at the Junior Colony, where many of the young people lived, worked, studied and grew. The boys did a large amount of the construction work in providing buildings for this center, and the girls cooked and made many of the clothes for the boys as well as for themselves. Here the young people performed the regular duties of industrial, home keeping and agricultural life and learned many practical things in the performance of these duties. Book knowledge was given as the need for it appeared. In this way a motive for learning was given the student.

“The plan is to take up a variety of subjects and teach the practice of, them before the theory is attempted. Thus in the one hundred acres of garden attached to the Industrial School and operated by the boys and girls, they will be taught soil chemistry, botany, horticulture, agriculture, and biology. These sciences will come so naturally to them that they will not be aware that they are being taught. Later when the theory is taken up, it will be thoroughly understood, because the facts have already been inculcated. Time usually wasted by children will be used in absorbing knowledge, yet the children will enjoy it all”.4

“The plan is to take up a variety of subjects and teach the practice of, them before the theory is attempted. Thus in the one hundred acres of garden attached to the Industrial School and operated by the boys and girls, they will be taught soil chemistry, botany, horticulture, agriculture, and biology. These sciences will come so naturally to them that they will not be aware that they are being taught. Later when the theory is taken up, it will be thoroughly understood, because the facts have already been inculcated. Time usually wasted by children will be used in absorbing knowledge, yet the children will enjoy it all”.4

“Self-government is also practiced. The boys have their managers of departments, make their own laws, try their own culprits, and acquire a sense of responsibility. They like it, for it is real life. Boys who have seemed to be incorrigible have been transformed into lovable, tractable, good-natured workers. They have received the attention they needed, and have been given an interest in life and healthful means of expanding their superabundant energy”.5 An attempt was being made in this department to eliminate all but the essentials of education and, for Llano del Rio, gave promise of success.

Bonds had been voted for a five thousand dollar school house, which was to take care of the children and of those in some territory not included in the colony. It was organized as any other school district and was under the same general supervision.

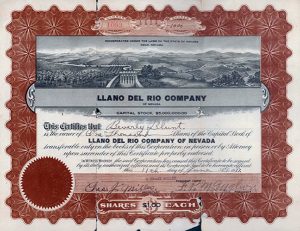

The Llano del Rio Company was incorporated under the laws of Nevada. As a corporation its business was transacted the same as that of any other corporation, and it had the advantage of a capital stock consisted of two million shares, the par value of which was one dollar.

The management of affairs in a general way was in the hands of the nine directors, who were elected by the stockholders of the company. They were the legal representatives of the company and as such were responsible to the State through the corporation laws. This board of directors appointed a superintendent of the colony activities, who was directly responsible to that body.

The management of affairs in a general way was in the hands of the nine directors, who were elected by the stockholders of the company. They were the legal representatives of the company and as such were responsible to the State through the corporation laws. This board of directors appointed a superintendent of the colony activities, who was directly responsible to that body.

The superintendent, with the sanction of the board of directors, appointed the assistant superintendent and the heads or managers of the various departments, who appointed the department foremen. Assistant foremen were appointed as needed in the different departments. The assistant superintendent and the foremen could be removed at the option of the superintendent and board of directors, the latter body having, of course, power to remove the superintendent. The board of directors could be recalled by a vote of sixty per cent of the stockholders. Thus we see the final authority came back to the stockholders, each having one vote regardless of the amount of stock held.

There were four distinct departments, with a fifth made up of several lines of activity, grouped together for convenience: (1) Farm, (2) Livestock, (3) Industries, (4) Construction, (5) Administration, Architects, Medical, Membership.

The rules and regulations of the managers, before becoming operative, had to be submitted to the board of directors. Managers and superintendent had regular office hours, so they could be easily reached by those who desired to talk over matters with them. In case of trouble or dispute, if adjustment could not be made by the managers or superintendent, the case was presented to the board of directors for final settlement.

The nature of the “contract” and the “Agreement of Employment” is interesting. Leading features included the following :

Each share holder agreed to buy two thousand shares of stock at the par value of one dollar.

Each agreed to pay one thousand dollars in money (cash at time of signing contract, if possible).

Each agreed to pay in labor, one thousand dollars.

Each received a daily wage of four dollars.

The one thousand dollars in labor could be paid by deducting one dollar a day from the four dollars daily wage.

Out of the balance of the three dollars wages the colonist bought his food and clothing from the company store and commissary.

The balance remained to the credit of the individual and could be drawn out in cash from the surplus profits of the colony (if such surplus ever accumulated).

A sum of not more than seventy-five dollars could be drawn each year in cash, which could be spent outside of the colony.

Continuous employment was guaranteed by the company, with provision for annual vacation of two weeks.

No stockholder could’ own more shares than other members.

It was very evident from the conditions of these contracts that all were to be treated alike, regardless of earning ability. The individual was lost sight of in the welfare of the community. All a man could expect — in fact, all he should want, according to the philosophy of the colonists — was the opportunity to earn what he and his family needed to eat and wear, and a place to live in peace and happiness. If he had private property, however, aside from what he had to put into his payments to the colony he was free to take care of it in his own way, but it could not be used in a productive capacity in the colony. He could have pictures, pianos, automobiles, or anything else in the colony which did not interfere with the productive or distributive processes of the colony.

The question was often asked if a single man was not at a disadvantage under this contract. In the first place, such a matter was not supposed to be worthy of consideration with these people. Then, too, if the credits were ever realized on in cash, the members who had made the smallest demands in food and clothing would get the most money.

It is most natural that many difficulties should present themselves in an undertaking of this kind. Some of the troubles of the Llano colony were very similar to those met with by earlier communistic settlements. However, it is probable that some of these difficulties were, as with other colonies, blessings in disguise ; they indirectly contributed, at least, temporary strength to the enterprise.

One of the handicaps to the rapid development of the Llano property and to placing it on a more productive basis was the lack of capital. Land had to be bought, water rights secured and developed, houses built, stock and machinery obtained, offices constructed and an advertising and selling campaign conducted, with very little capital outside of the money derived from memberships. This necessitated a large use of credit and a very frugal use of the resources for even the necessities of life. The common necessity, however, made for community thought and action.

Llano del Rio, like many of the earlier colonies of the country, experienced periods of social unrest and dissatisfaction.

This condition was inevitable unless many applicants were excluded and only people of common ideals, harmonious and select, were permitted to become members. While a more careful and conscientious sifting process might have worked for the ultimate good of the colony, it would have been a hard policy to pursue during the early days when funds and labor were both so much needed in the development work.

The Llano del Rio Company was originally organized under the laws of California and, although later operated under a Nevada charter, it was subject to the laws and regulations governing such corporations in this State and also subject to inspection and super vision by the Commissioner of Corporations. During 1915, com plaint against the management of the colony was made to the Commissioner, which resulted in his appointing Deputy Commissioner H. W. Bowman of Los Angeles to investigate the company affairs generally. Mr. Bowman’s report was submitted to the Commissioner December 31, 1915, and contained material of value in this discussion. This report resulted in the Commissioner of Corporations issuing specific instructions to the company governing the sale of stock, at the time the permit authorizing such sale was made.

Shortly after this thirty-two dissatisfied colonists withdrew from the colony, and in a signed statement presented to the Commissioner of Corporations declared that the colony, organized as a cooperative enterprise, having for its purpose mutual helpfulness, had become a one-man autocracy, an organization dominated absolutely by Mr. Harriman, who ruled arbitrarily and often without a semblance of justice. Although the statement was not specifically made that Mr. Harriman’s management was in his own interests individually, it is an implication that such was the case.

This was followed in a few weeks by a reply to the report of Mr. Bowman and the charges of the colonists who had withdrawn, written by Mr. Harriman.

Mr. Bowman’s report to the Commissioner of Corporations was comprehensive and well arranged. It was submitted in the analytic ‘ style in which attorneys’ briefs are usually submitted. It was written apparently in the spirit of a public official who had discovered a situation which needed, in his opinion, the firm and careful exercise of the law in order to remedy a condition which was producing injustice to a number of citizens of the State.

Mr. Harriman’s answer, on the other hand, was written to justify the conduct of affairs by the company officers. It explained from the official viewpoint the reasons why actions cited in Mr. Bowman’s report as unwise and unjust, were taken. His position was that many of the official acts of himself or the directors of the company, were not only justifiable, but wise, and in the interests of the company as a whole, and, if understood, would be viewed by others in that way.

It is neither necessary nor wise to go into a detailed discussion of this controversy in this paper. It was difficult for each side to appreciate the position of the other, and some injustice probably resulted. However, the final result was no doubt beneficial to the colony and brought about a closer supervision of the company affairs by the Commissioner of Corporations.

The personnel of the colonists is interesting. About twenty-five per cent of the members were Californians and, as might be expected, a majority came from west of the Rocky Mountains — at least sixty to seventy per cent. Recruits came from the South, the Middle West and the East, but they were comparatively few in number. The several occupations of the colonists prior to their coming to Llano are an interesting study. On June 26, 1917, a survey showed that six had been engaged in transportation, fifteen in professional lines, five in the printing trades, ten clerks, eight miners, eighteen workers in manufacturing plants, seventy-three in business lines, thirteen in building trades, and one hundred four farmers.

There were few foreigners in Llano. Nearly all were so far removed from foreign parentage that they would be classed as Americans. Their habits, thought and ideals were formed by American influences.

The character of the members of the colony was above what I expected to find before my visit there. The leaders were wide awake men of affairs, several of whom had had very successful private business experience.

As one conversed with the people one was impressed with the fact that, for the most part, they were men and women of intelligence and common sense. They were not there because they were “down and out” and unequal to the struggle of life. If that had been the case they would have been unable to raise the necessary funds to become members of the colony. They were largely substantial persons who had banded themselves together to attempt to work out a community life that was without a capitalist and where the fruits of toil went where, in their estimation, they belonged, to the laborer.

In the fall of 1917 it was decided by the directors of the company that a change of location of the home or mother colony would be beneficial. It was urged. that progress would be more rapid, and prosperity and ultimate success more sure, if the colony were located in a section of the country with larger agricultural possibilities. The proposal was agreed to by the colonists, and in November, 1917, the company interests, material and spiritual, were largely transferred to Stables, La. Here a tract of sixty thousand acres, well provided with buildings, had been purchased, which was to become the new home, the new center of this communistic enterprise.

Reports from; Stables indicate progress, and those who have watched developments in California will observe with interest the colony career in Louisiana.