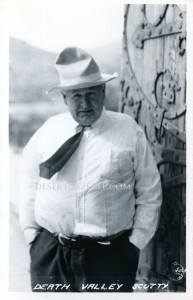

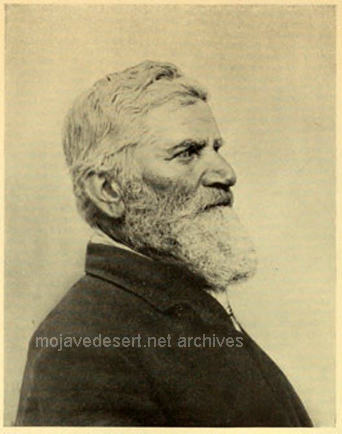

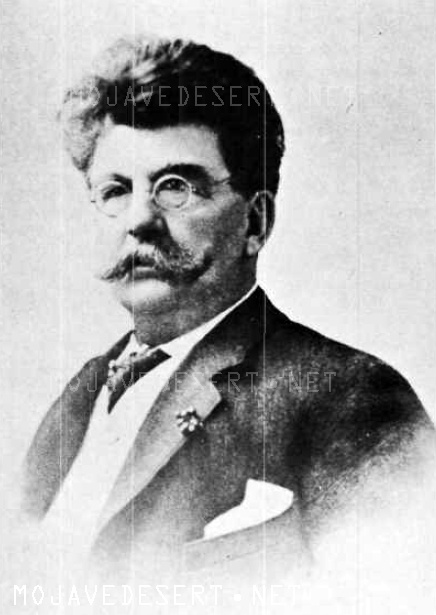

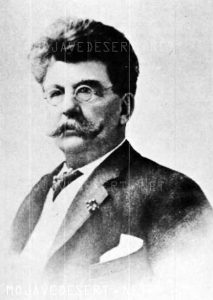

– A.K.A. Charles Tom Vincent –

This story was derived from Chapter 5 of Pearl Comfort Fisher’s “The Mountaineers,” written by Dorothy Evans Noble and edited by George F. Tillitson

Dorothy Evans Noble, former postmistress at Valyermo and wife of geologist Dr. Lee Noble, wrote this memoir of the Serrano Old Man Vincent whose name was given to Vincent Gap and Vincent Saddle. Mrs. Noble wrote that the memory of the man might not be lost. She gave it to the United States Forestry Service (USFS) who graciously accorded Pearl Fisher to include it in her book, “The Mountaineers.”

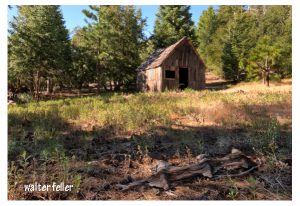

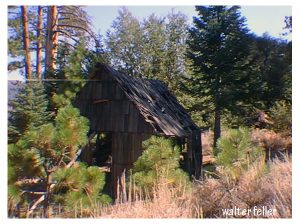

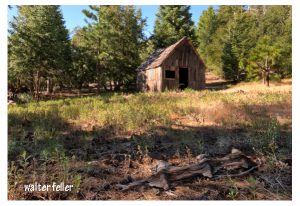

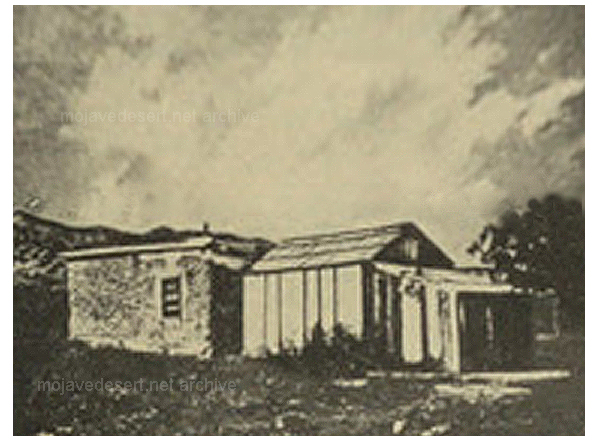

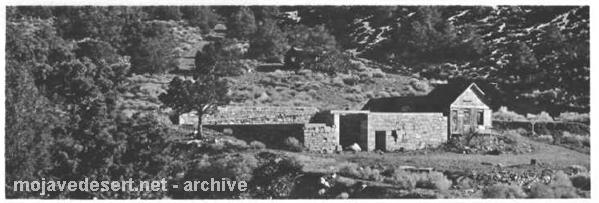

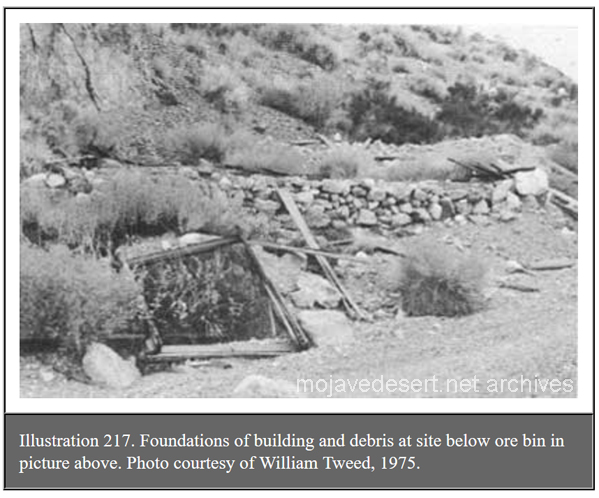

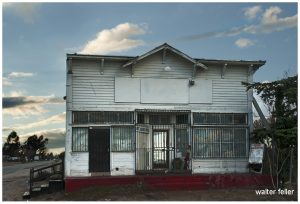

Restored cabin

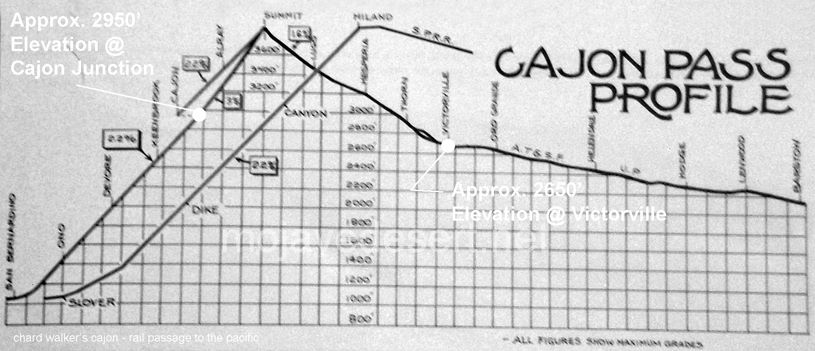

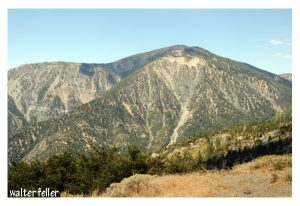

Old Man Vincent’s daily newspaper came to our small post office at Valyermo, California, but he never did. Our nearest neighbor, Bob Pallett, who had a cattle ranch adjoining our fruit orchards took his mail to Vincent once a month when he took supplies by horseback to the cabin twelve miles up Big Rock Creek on the slope of North Baldy Mountain (now Mount Baden-Powell). It was a steep trail from our thirty seven hundred fifty foot altitude to Vincent’s sixty six hundred foot. Bob said he was a sort of hermit who hated all women and most men, chasing visitors off his land with a rifle and spending all his time mining gold and shooting game. He liked Bob and depended on him, and Bob enjoyed sessions with the old man. We heard stories about Vincent for three years before we ever saw him.

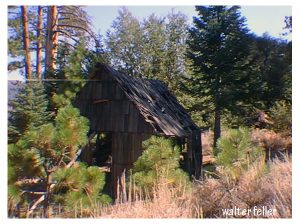

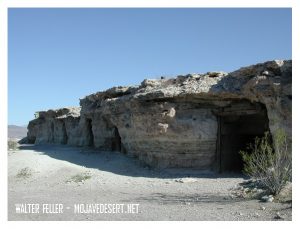

Original cabin – 1999

The first week of April 1914, brought such frightful news of war in Europe that ranch work seemed futile and we decided on a sudden walking trip into the mountains to think things over. A geologist, Greg, was visiting us and we three set out on foot to climb Mount Baldy. We took Vincent’s mail with us. It was a long climb up to Vincent Saddle at the head of Big Rock Creek where we followed a trail high on the slope of the mountain for a mile and looked down on a neat clearing with a small gray cabin shaded by two tremendous spruce trees. We skidded down the hill, slippery with pine needles, and zoomed right to the cabin door which opened with a bang, and Old Man Vincent faced us rifle in hand.

“Who in hell are you?” was his greeting.

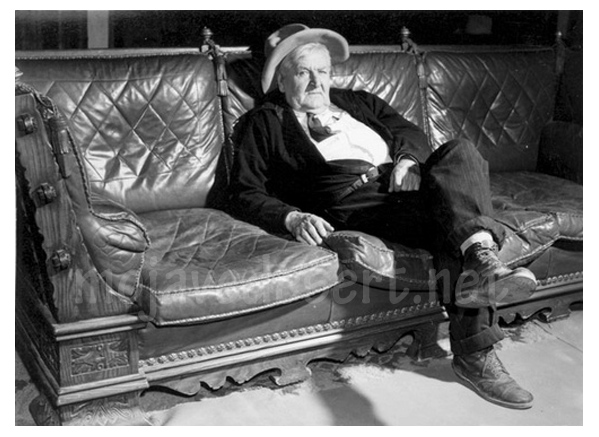

He was a sight to remember, a thin old man in blue jeans and a faded blue shirt that barely covered his barrel chest, with piercing blue eyes that glared from under tufted white eyebrows and a little white beard under an aggressive chin.

Before we could explain he spotted the bundle of mail my husband held out, made a grab for them, yelling “Papers? Good.”

He dashed back into the cabin, slammed the door and slid the bolt inside. We sat down for a while on his woodpile, glad for time to take in the good lines of the cabin with its steep roof and chimney, all in the shade of its sides weathered to a soft gray that blended into the bushes and pine needles around it. There was water in a moat, a small ditch that circled the cabin, fed out of a pipe at the back where icy cold water dripped into a barrel. Two small tents nearby and a big meat safe hanging from a limb of the largest spruce aroused our hope of a friendlier reception later.

Suddenly the door burst open and Vincent charged out, waving a newspaper and screaming with excitement.

“Say, is it really true, is it war?”

And when we confirmed the awful truth he was wild with joy, not distressed at all.

“Fine, fine, I ain’t died too soon. War’s the stuff I like. Maybe we still got some real men in the world after all. Let ’em fly at it, rip things up, git a little action to stir things up. Shoot, kill, that’s the life.”

Nothing was too good for us from then on. He took us into the cabin cross-questioning us as to the number of men killed so far and insisting on our spending the night with him after we climbed the mountain. He even went with us part way.

Tired by the long climb we were delighted to find Vincent busy with a pot of savory stew made of jerky (dried venison), onions, potatoes; and one of beans. He had fixed beds of boughs in the tents for us and set places in the rickety little homemade table by the stove. He let me make the green tea and wash the dishes later while the men talked war. Vincent stretched out on the bunk, Lee and Greg perched on the other and by bedtime we were all old buddies, beginning a friendship that lasted as long as the old man lived.

A loud bellowing of song woke us the next morning.

Vincent was fixing breakfast to the tune of “If you get there before I do, Tell Old Jack I’m comin’, too,” followed by “Fifteen men on a dead man’s chest, Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum.” He described the battle of Gettysburg while we ate, claiming that no losses in Germany could equal those bloody days. He was wounded there and sent back to Conneut, Ohio, his birthplace. He was a member of Company F, 8th Ohio Infantry and proud of it. As we left him that day he barked at me,

“Don’t you ever come back here again.” And when I gasped, he added, laughing. “Unless you stay a week here.”

I had heard of his remark to a silly Los Angeles woman who had come to thank him for letting her use water from his ditch when she camped nearby. She had minced in and grabbed his hand, saying,

“I do hope I’ll see you in the city sometime.”

His retort was, “I hope I never see you again, Madam.”

So we realized that the ice was broken for us. From then on until his death in l926 Vincent was our close friend and real companion. We often spent a week or two with him and when we found his birthday was on Christmas Day we formed the habit of having him with us for the day. The first time he came he told us that it was the first Christmas dinner he had not eaten alone in fifty years.

The last Christmas dinner he ate with us when he was feeble, but he polished off two big slabs of his favorite dessert, mince pie liberally laced with strong, homemade applejack. Bob Pallett asked him the next day how the pie “set.” Vince’s reply was,

“Swell, you bet. Course all night I thought sixteen jack rabbits was loose in my stomach but it was worth it.”

I had pulled a boner that day by saying I wished he had brought his glasses along so he could write in our guest book. He was outraged, said he never needed glasses, that no one ever would who lived outdoors and followed deer tracks instead of ruining his sight poring over books. Vincent’s sight was really remarkable for he could spot a moving object miles away, and also read close up even in his eighties. Stretched out on his bunk of an evening he put a lighted candle on his barrel chest, between the “Los Angeles Times” and his eyes pored over every item. He kept his books under his bed, a few old favorites that he read over and over. A copy of “Life of Napoleon” and one of “Treasure Island” were read most. A bottle of whiskey flanked them but he drank from it seldom.

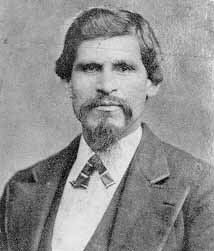

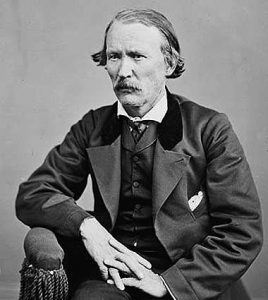

Vincent loved to talk and he had a gift of understatement and a pungent way of expressing himself that was masterly. He wasted no words and omitted unnecessary details. His pet subject was the Civil War, particularly the Battle of Gettysburg where he was wounded in July of l863. He and a pal named Lockwood had enlisted as lads and after the war they went home, planning to set up in business together with their families’ help. This was refused so they set off for good on horseback, heading west. They left in a fury and never communicated with their kin.

The story of that trek was fascinating. They decided to prospect for gold and in Arizona they found rich claims, filed on them, built a shack and set to work. Vincent never would explain why they moved on, just said they had trouble and shoved on for California on horseback. He told of crossing a river and stopping to swim in it, leaving their clothes on a bank. They spied an Injun sneak up and make off with their clothes. He waited for us to ask how they got them back, then just said,

“That Injun never stole nothin’ more. I took off after him. I got the clothes.”

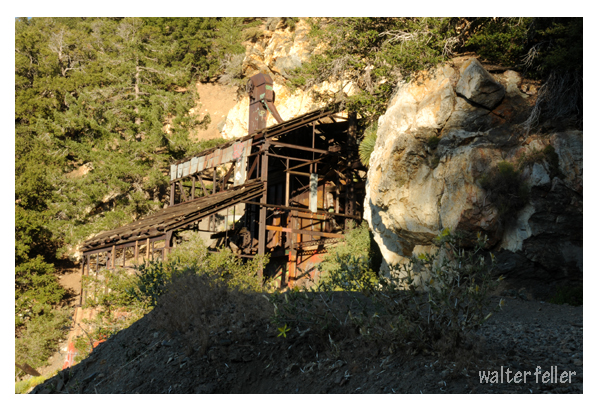

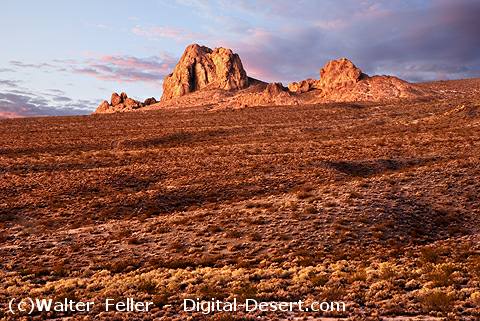

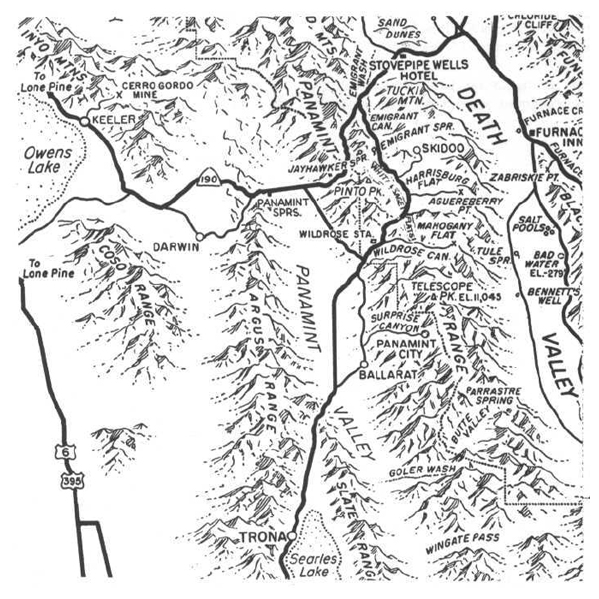

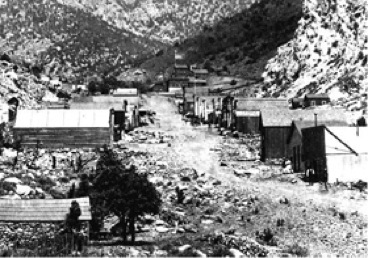

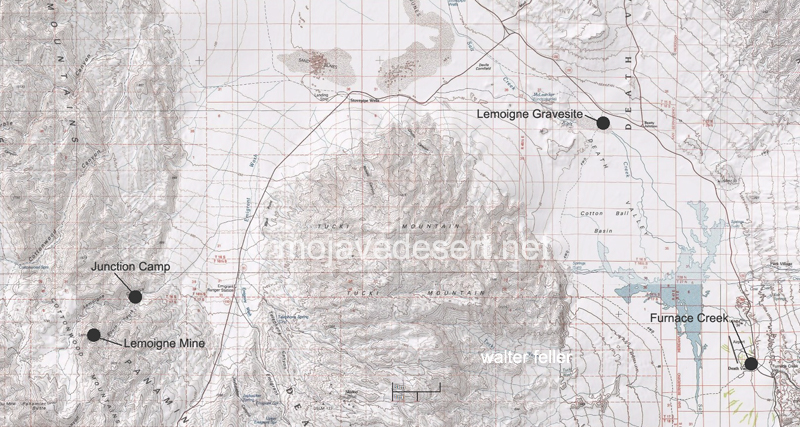

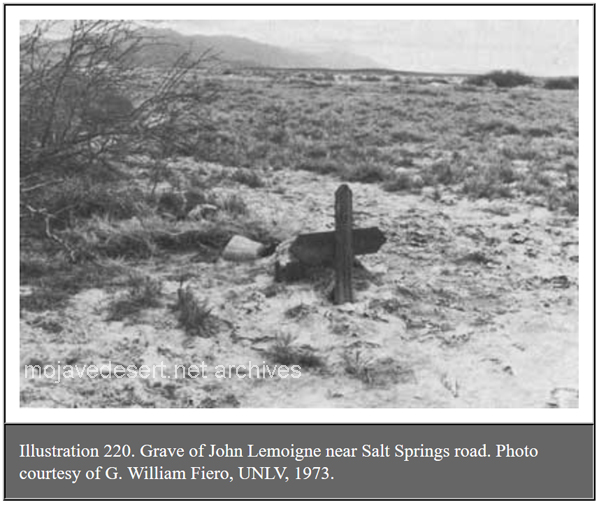

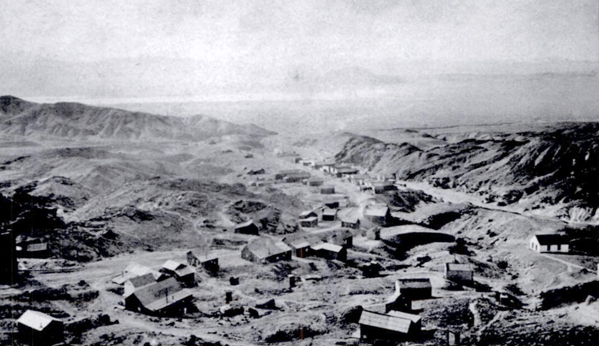

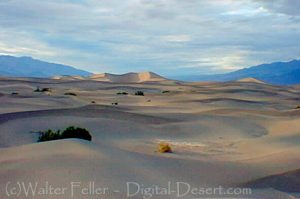

They finally reached Los Angeles, a nice little town in l868 but too citified for Vincent. Lockwood settled there, but Vince prospected the mountains for months all over the region, even going to Death Valley and the Sierra Nevada country. Nothing suited him until he happened on Big Rock Creek on our edge of the Mojave Desert and rode up its source on the slope of North Baldy Peak, camping on what is now known as Vincent Saddle, the divide between Big Rock Creek and the beginning of the San Gabriel River. His first claim was located away from the slope beyond steep, rocky Mine Gulch, and he named it Big Horn because he killed a mountain sheep there. This claim he later sold and it was developed by a mining company into a rich, high grade mine which ultimately produced many thousands of dollars.

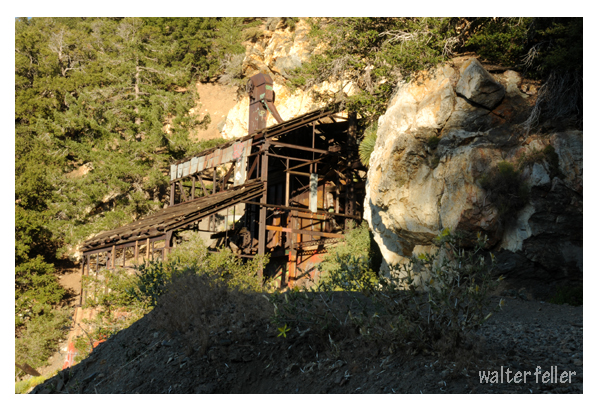

Bighorn Mine

The location at Big Horn did not suit Vincent so he continued prospecting until he found one that did, a flat wooded place with fine big timber and a spring near enough to provide water after he had dug half a mile of ditches. He had adapted a kitten by that time, a Maltese gray, and he named the new claim he had found Blue Cat. It was near Mine Gulch, about half a mile from the flat place which meant more ditches and trails. Then he tackled building his cabin which stands intact to this day. (By the thirties it had collapsed into ruins but not until after Nancy Templeton did an oil painting of it. Maxine Taylor did an oil painting of Vincent’s Cabin in the mid l980s. Her painting is reproduced herein.)

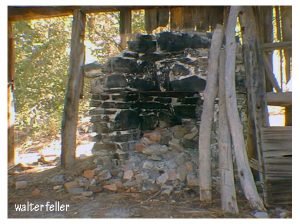

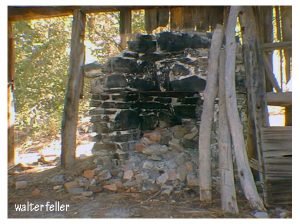

He hand-hewed shakes (shingles) from the trees, built a stone fireplace in one end, put up the one-room, steep- roofed cabin with just one small window and a door. He made two bunks, one on each side of the fireplace, two arm chairs and a small table. He said he worked too hard to be lonely for when the cabin was finished he had the mine to timber and later made a small stamp-mill with a Pelton wheel run by water from his spring.

He had help after a few years when he sold Big Horn and that company built a good trail on the slope above the cabin so a heavy stove was moved up and cement to mix with the rocks for a cabin floor. Another prospector built a shack away from Vincent’s but “The Nigger” as Vince called him, although his name was Delancey and he wasn’t colored, and Vince fought like cat and dog. But Vincent lived on solitude by choice for forty years, working on his tunnels and ditches, hauling ore back by wheelbarrow to the stamp mill, to refine by running crushed ore over a mercury chute, then sacking the gold to take to the city once a year.

The winters must have been grim at the altitude of sixty six hundred feet, but he had a huge woodpile at hand, lots of dried venison stored up, beans and canned tomatoes, potatoes and onions laid away by late fall. Summers are lovely and cool there, and nine months of the year hunting was fine sport; deer and mountain sheep, quail, rabbits and doves all made good food and he could catch fish in Vincent Creek.

By the time we knew Vincent the cabin had every comfort heart could wish, and Bob Pallett to haul freight from Palmdale once a month he could relax and live the life of Reilly. The big screened meat safe that hung from a spruce tree, out of reach of bears, was full of venison for there was no closed season then and Vince would have disregarded if there had been. A picture of McKinley hung over the old man’s bunk and a goldpan and rifle were fastened to the chimney. Every afternoon when he came in from work he stripped to the buff and threw a potfull of hot water over his strong, rugged body, regardless of company; so we learned to vamoose. He was strong as an ox, the picture of health, thin and wiry with pink cheeks and snowy white hair. He could and did, walk for miles tracking a deer and he never fired an unnecessary shot. He loathed the city fellers that banged away regardless, when after game. Once we asked him what sort of winter’s hunting he had had, and he said,

“Only fair. I missed one shot clean. Took me six shots to get my five deer.”

When he killed he dressed the deer on the spot, packed as much on his back as he could carry home, then made trips back to get the rest. Hunting meant a food supply, not sport, to him.

He was a crank about coffee which must be strong and coal black. When I made the coffee one morning and asked him if he wanted a second cup, his answer was,

“Well, yes I do, but God it’s weak I don’t see how it gets up the spout.”

His pet comment was “Strong coffee never hurt no one, but weak coffee is pizen.”

He called Postum “Potassium” and was scornful of it, and he always pronounced boulevard “bovelard” and brooked no correction. He drank what little whiskey he imbibed straight, scorning fancy drinks. Once we took some rare old sherry up for his pleasure and sat by the fire with cups of it, expecting a nice session of talk. Vincent took one sip out of his cupful, swore, spat it angrily into the flames and threw the whole cupful into the fire.

“God, what truck,” he said. “What’s wrong with whiskey that anyone bothers with this hogwash?”

Even with the Palletts the old man was secretive, so we sensed some mystery in his past. The way he kept his cabin window boarded up unless he was inside, his fury when anyone tried to take his picture, his refusal to let anyone else go to his Los Angeles post office for his pension checks, all added up to some secret. We never dared to refer to a penciled name we once found in one of his old books, for it said “Mrs. Charles Vincent” so we supposed it concerned a wife he’d had sometime. Only once did any relative show up, a cousin from Conneaut brought to him by Lockwood, who insisted on Vincent’s attending a dinner at her home in Glendale.

Later we wormed the story out of him to our lasting amusement. He went, they had a swell meal, and then

“Durned if she didn’t get out a big book of postcards, pasted in, and she begun on ‘my trip to Europe’ page by page. I had come by trolley and I happened to see one startin’ down the street, so I said ‘Goodbye, Ma’am, here’s my car’ and I run out and hopped on it. She won’t see any more of me.”

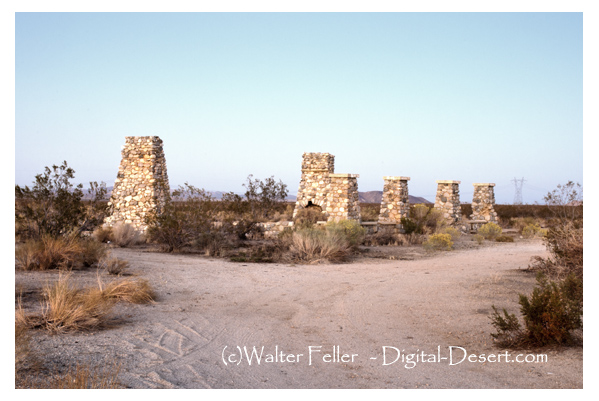

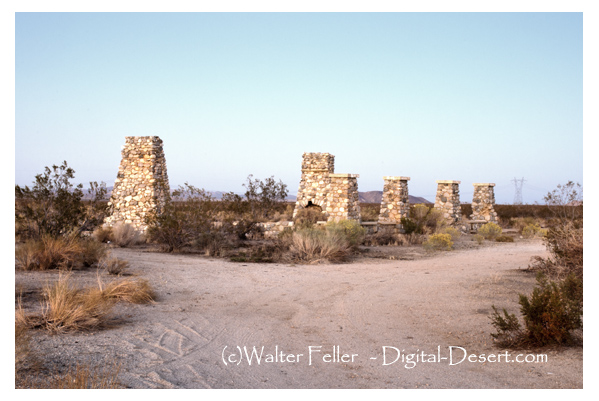

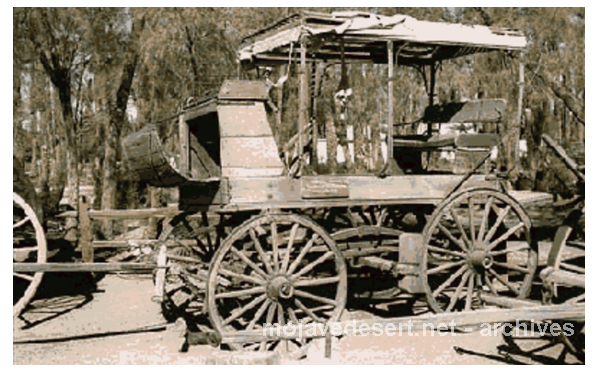

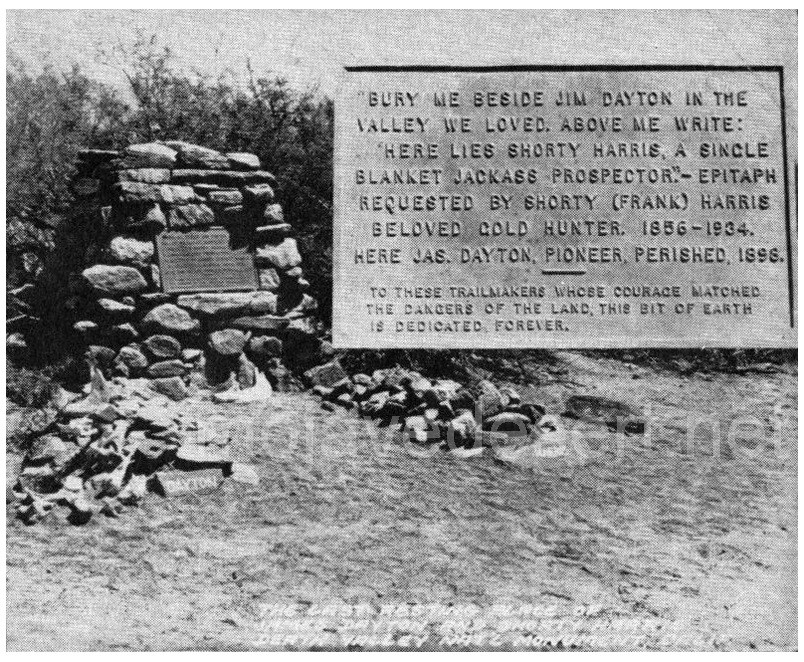

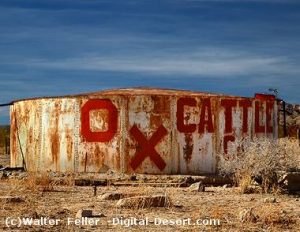

Socialist colony ruins, Llano, Ca.

He had great scorn for the developments in southern California. He referred to the Socialist colony (Llano) that settled on the desert below us as a “nest of vermin” and he fulminated against Pasadena and other fancy towns.

“This country’s the next to git its lickin'” he once said. “I’ll bet I live to see the Japs amarchin’ up Broadway. I sure would like to see a troop bivouacked on them Pasadena lawns.”

Vincent was hipped on cleanliness and order, kept everything in its appointed place and did his washing regularly. He told me once about some campers who had stayed nearby, and his comment on the woman who cooked was

Vincent was hipped on cleanliness and order, kept everything in its appointed place and did his washing regularly. He told me once about some campers who had stayed nearby, and his comment on the woman who cooked was

“Say, that there woman was a caution. You could plant a potato patch on the back of her neck. I often seen dough on her elbow from last week’s bakin’. Water didn’t bother her none.”

Before he dug a moat around the cabin and ran water in it he was bothered by ants, for he bought sugar by the sack, and he told us,

“Ants got all through the sack and I couldn’t sift them out. So I jes hauled it down to the M—– family, it was all right for them, they didn’t notice.”

He stayed at the cabin winters until, when he was eighty three, he carried a quarter of deer back to the cabin from away up the slope of Mount Baldy and collapsed from the effort, so we had to take him to Los Angeles to our doctor, a heart specialist. He was taken to the hospital and kept there for several months as he had a torn ligament of one of the arteries to his heart. We feared he was done for, but he came back in good style and lived for years after that, though he could no longer spend winters at the cabin and moved into a tent house by Big Rock Creek on the Pallett Ranch.

I remember his first Christmas holiday there when he came to the post office to cross question me about a geologist who had spent the holidays working on our geology.

“Say, Noble,” said he, “What kind of a dam fool was that feller anyway? I was settin’ by my tent, watching the creek in big flood with the bridge washed out and all, and I heard a big splashin’ and seen this guy wadin’ across in water up to his waist. Up he came and durn if he didn’t tip his hat and say,

“‘Excuse me, sir, but could I trouble you for a drink of water?'”

At intervals Bob Pallett would call us up to say Vincent had collapsed and we would hurry him to the city to install him in the hospital, expecting each trip to be the last. Not so, he came to time after time, and he would chortle over his fooling the doctors.

“They hung around my bed like crows around a dead horse,” he would say, “Waiting to see me die.”

The nurses took a great shine to the game old man and he was a favorite there.

“I like that place,” he said. “Best coffee in Los Angeles there.”

Once I visited him there and he introduced me to his pet nurse. I asked him her name and he said it was “Scenery.” When I looked puzzled, he explained.

“Seems as though the head nurse complained because so many nurses came in to talk, so one day they heard her comin’ down the hall and this nurse, she got excited and run. She tripped over the rug on her way out and, say, some scenery I seen. That’s been her name ever since.”

Vincent was a baseball fan and made yearly trips to Los Angeles to see the games. He would take with him the small sack of gold he had refined from the “Blue Cat” and “Little Nell”, another mine he had developed and named for his pal Lockwood’s daughter Nell; would cash it in and put in a safe deposit box. He had a post office box in the city where his Civil War pension checks came, and he would cash them, too, and put them in the box. When Bob Pallett fell on hard times and was about to lose his ranch he was astonished to have Vincent produce five thousand dollars in cold cash and present it to him.

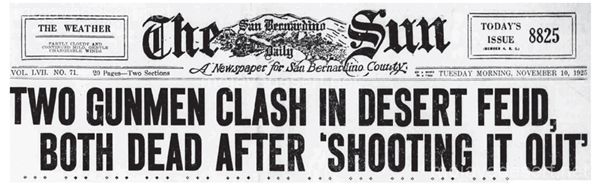

On September 8, l926, our doctor phoned to say that Vincent was dead and was to be buried on the thirteenth at Sawtelle, the Veterans Home. He had died in the hospital and had told the doctor his life secret in order to assure his burial in the soldiers’ graveyard. So the Palletts joined us in the drive to Sawtelle where we went to the chapel, asking for the Vincent funeral.

The Veteran’s Chapel for funerals is divided by a crosswall so that two services can be conducted at the same time, one for Catholics and one for Protestants; so we made for the Protestant part only to learn that no Vincent funeral was slated for that day but a Dougherty funeral was. We were baffled. A Catholic soldier was slated for the other side.

Then a car raced up and our doctor’s secretary rushed up to tell us that Vincent’s real name was Dougherty, so the service went through as scheduled, and we all followed the body which was placed on a double gun carriage with that of the Catholic soldier and taken to Section 9, Row G, Grave 22, in the lovely green cemetery where hundreds of veterans’ graves lie in neat rows.

Bob Pallett whispered, “You’d sure have to hold Vince down if he knew he was on that gun carriage with a Catholic!”

Then our doctor told us the amazing story Vincent had told him a few days before. He had used his real name, Charles Vincent Dougherty, until a stay in Arizona in 1866 where he and his partner had found gold and staked out prospects. they planned to stay there as the claims were rich and had built a shack and worked away happily in that wild, deserted country. One evening they found three strange men in the shack.

One said he was the sheriff and was checking up on claims. Vincent and Lockwood didn’t like the looks of these men and decided to spy on them. They left the men talking in the shack and went out pretending to work outdoors, crept up at dusk to overhear them talk. The three men were laying plans to jump the claims, do away with the partners and take over. Vincent and Lockwood beat them to it, shot all three in a surprise attack and buried them there and then.

Then they lit out as fast as they could on their horses and fled to the wilder west. They expected to be followed, not realizing that no law force existed then, so they changed their names and hid out the rest of their lives though no one came after them. Vince chose his middle name, Vincent. Of course they had to abandon their rich claims, but Vince knew he could find others as he did later. That is why he never allowed anyone to take his picture, why he barred the one window in his cabin at night, why he suspected strangers, why he had a mail box in Los Angeles to have Dougherty pension checks come to.

The doctor said he would never forget that talk, the fiery old man blurting out the old, old secret, not one bit repentant; proud of his past.

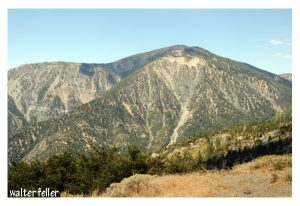

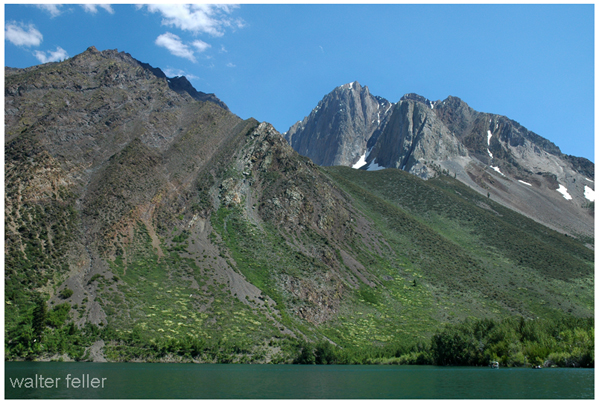

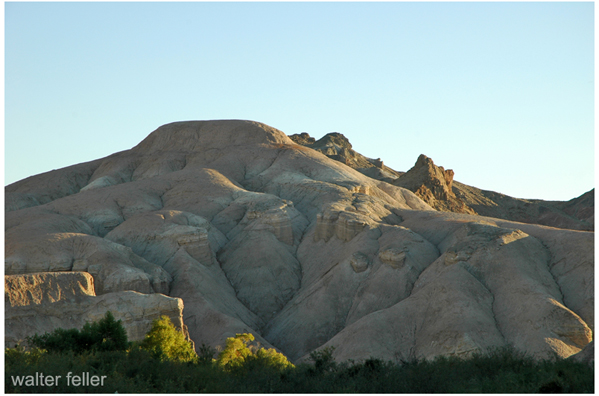

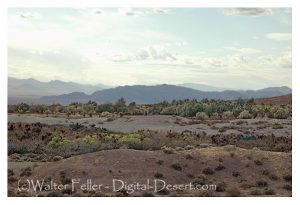

Mt. Baden-Powell

He was a fighter, from his boyhood days on through Gettysburg and his trip west, and his one desire was to be buried with other fighters as he is. He was taught to kill in the Civil War; he considered the Arizona killings a matter of self-defense; he loved to show his skill in shooting but never killed an animal except for food. His unending labor made him a veritable Robinson Crusoe on a mountainside, slaving away day after day to make a comfortable life for himself. He loved the life he led. His magnificent physique kept him from illness, he was full of high spirits and was entertaining a companion as we have ever known. Always kind and generous to the few he liked, all his friends agree Charles Vincent was a Man.

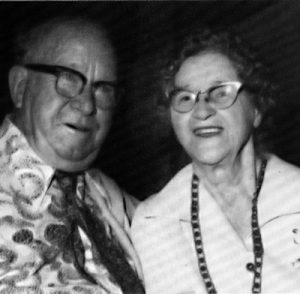

Courtesy Wrightwood Historical Society

-.-

Death Valley was having one of its periodic wind storms when the tourists drove up in front of Inferno store to have their gas tank filled.

Death Valley was having one of its periodic wind storms when the tourists drove up in front of Inferno store to have their gas tank filled.

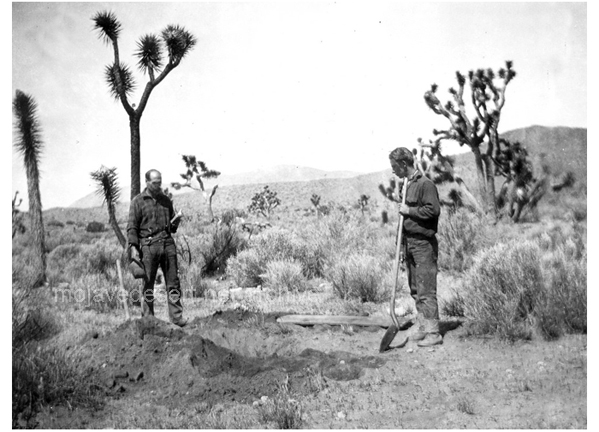

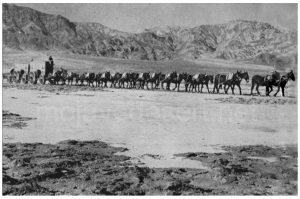

Sandy Walker says you can’t find gold with Fords – have to have burros. Says he’s been out here in the desert 26 years, 6 years hunting gold and 20 years hunting burros. He didn’t find his mine while hunting gold. He found it while hunting his dadburned runaway burros.

Sandy Walker says you can’t find gold with Fords – have to have burros. Says he’s been out here in the desert 26 years, 6 years hunting gold and 20 years hunting burros. He didn’t find his mine while hunting gold. He found it while hunting his dadburned runaway burros. The word Mojave (or Mohave) itself is of Indian origin and is that tribe’s name for “three mountains,” referring to three distinctive landmarks near the present city of Needles, whose name also refers to this geological oddity.

The word Mojave (or Mohave) itself is of Indian origin and is that tribe’s name for “three mountains,” referring to three distinctive landmarks near the present city of Needles, whose name also refers to this geological oddity.