Combined timelines of Victorville, Hesperia & Apple Valley, CA.

Pre-1800s: Indigenous Presence and Trade

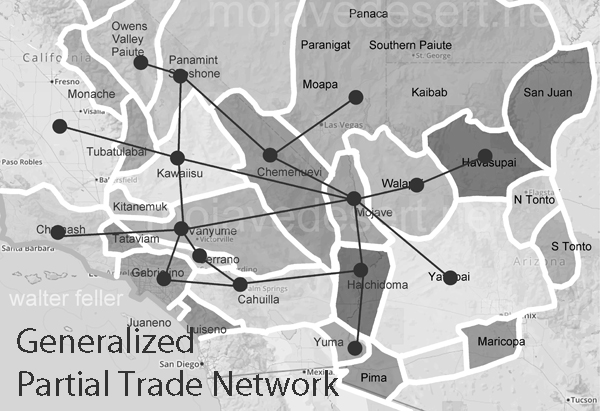

- The Serrano and Vanyume tribes lived along the Mojave River, relying on the river’s intermittent flow for food and trade.

- Trails used by these tribes would later become parts of the Mojave Road, Old Spanish Trail, and Salt Lake Road.

1850s–1870s: Pioneer Waystations and Early Ranching

- 1858: Aaron G. Lane establishes Lane’s Crossing on the Mojave River (present-day Oro Grande/Victorville area), offering rest and resupply to travelers heading west.

- Lane is considered the first permanent American settler along the Mojave River.

- Summit Valley, near present-day Hesperia, sees increased grazing by early ranchers.

- The Summit Valley Massacre (1866): A conflict between settlers and Native groups over livestock thefts and land disputes—an often overlooked but significant local tragedy.

1880s: Railroads and Town Foundations

- 1885: The California Southern Railroad, part of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe system, reaches the High Desert.

- A telegraph and railroad station named Victor is established, later renamed Victorville in 1901 to avoid confusion with Victor, Colorado.

- Jacob Nash Victor, the railroad manager, is the town’s namesake.

- The Hesperia Land and Water Company, led by James G. Howland, promotes Hesperia. It lays out plans for an agricultural colony and resort town, though irrigation plans fall short.

1900s–1930s: Modest Growth and Agriculture

- Hesperia experiments with vineyards, orchards, and dairy farms, but water shortages and harsh conditions hinder success.

- Victorville grows as a railroad shipping center and stopover for travelers crossing the desert.

- The Victor Elementary School District is formed in 1906.

- Early buildings still visible include the Hesperia Schoolhouse (Main St. and C Ave.).

1940s: War Changes Everything

- 1941: Victorville Army Airfield (later George Air Force Base) is established on the western edge of Victorville.

- The base brings thousands of military personnel, rapid infrastructure growth, and federal investment.

- Apple Valley remains mostly desert ranchland, but interest grows due to its mild climate and open space.

1948–1950s: Apple Valley Booms

- 1948: Apple Valley Inn opens, built by Newt Bass and Bud Westlund to attract investors and wealthy land buyers.

- Stars like Bob Hope, Marilyn Monroe, John Wayne, and President Eisenhower stay at the inn.

- Murray’s Dude Ranch (founded earlier, 1920s–30s): One of the few Black-owned resorts in the country. It hosted African American guests during segregation and was used in Black-cast Western films.

- Roy Rogers and Dale Evans buy a ranch in Apple Valley and become its best-known residents, eventually opening Roy Rogers’ Apple Valley Inn.

1950s–1960s: Expansion and Identity

- Hesperia Inn and the Hesperia Golf & Country Club try to rekindle resort dreams. Jack Dempsey, the former boxing champion, lends his name to a museum at the inn.

- Victorville grows with new housing and infrastructure to support the military population.

- Route 66 runs right through Old Town Victorville, lined with diners, motels, and neon signs.

1970s–1980s: Steady Growth and Cultural Legacy

- Apple Valley becomes a desirable retirement destination, marketing itself as a “Better Way of Life.”

- Civic leaders like Bud Westlund and Newton Bass help shape the town’s modern layout and community services.

- The California Route 66 Museum opens in Victorville in a former café, preserving the highway’s local legacy.

1992–2000s: Transformation and Reinvention

- 1992: George Air Force Base closes under federal military restructuring, dealing a blow to Victorville’s economy.

- The base is repurposed into Southern California Logistics Airport (SCLA), an international freight and aerospace hub.

- Apple Valley, Hesperia, and Victorville begin to urbanize, growing into commuter towns for the Inland Empire and Los Angeles.

2000s–Present: Modern Challenges and Historic Preservation

- Victor Valley College, founded in 1961, continues to serve the region.

- Old Town Victorville Revitalization Project aims to preserve the historic downtown.

- Apple Valley promotes its Western heritage through the Happy Trails Highway and events honoring Roy and Dale.

- Hesperia Lake Park, Silverwood Lake, and local trails draw new visitors and recreation seekers.