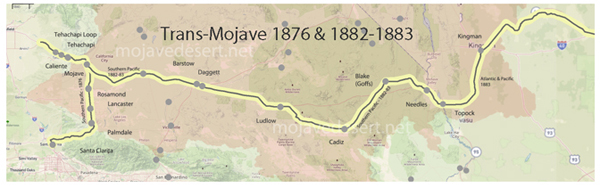

Initially, negotiations between the California Southern and the Southern Pacific over securing a route from Needles to the Pacific Coast proved difficult. The Southern Pacific, which held effective control over the only existing line across the Mojave Desert, was in no hurry to assist a potential rival. The Southern Pacific’s leadership, accustomed to monopolizing rail access into and across California, viewed any arrangement that would aid an eastern competitor with deep suspicion.

Faced with obstruction and unreasonable demands, the California Southern and the Atlantic and Pacific Railroads—both closely tied to eastern capital—announced a bold plan. If the Southern Pacific would not cooperate on reasonable terms, they declared they would jointly undertake the construction of an entirely new and independent railroad across the desert. This proposed line would have paralleled the Southern Pacific’s existing track but remained free of its influence, offering the first serious threat to the Southern Pacific’s dominance over desert transportation.

The announcement was not a mere bluff. Surveys were conducted, routes were studied, and eastern investors, eager to establish a competitive foothold in the California market, were prepared to finance the new line. The specter of competition alarmed the Southern Pacific. It recognized that the construction of a rival road could undermine its existing investments, dilute its control, and establish a permanent eastern presence in southern California on terms not of its choosing.

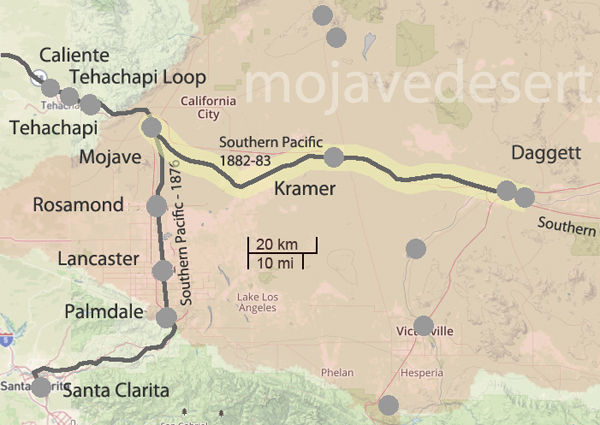

Rather than risk this costly and uncontrollable outcome, the Southern Pacific relented. In a calculated move to protect its broader interests, it agreed to sell the California Southern the existing line between Needles and Mojave. This line, originally built by the Pacific Improvement Company—the Southern Pacific’s construction arm—was turned over in October 1884. In doing so, the Southern Pacific avoided the rise of a parallel competitor while still extracting a financial return on its desert investment.

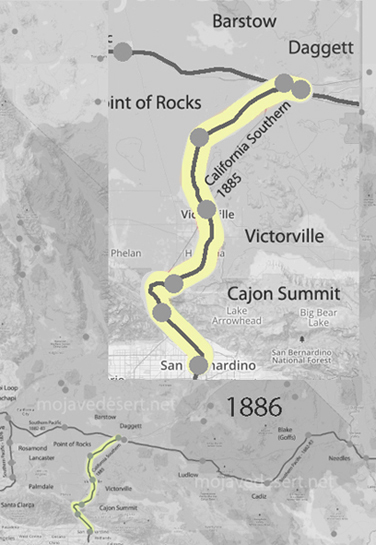

The transfer was a turning point. With control of the Needles-Mojave line secured, the California Southern could at last resume construction in earnest, repairing flood damage and completing its transcontinental link. By late 1885, trains could run from San Diego to Barstow, and by 1886, the California Southern itself had been acquired by the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway, effectively sealing the eastern invasion into California’s rail market.

California Southern and Atlantic and Pacific Railroad: Timeline with Notes (1880–1886)

- October 12, 1880 – Charter Granted

The California Southern Railroad Company is chartered to build a line from San Diego to San Bernardino, opening a new southern route to inland California. - May 23, 1881 – Extension Planned

The California Southern Extension Company is chartered to extend the line northeast to connect with the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, originally aiming for a point about 80 miles from San Bernardino. - August 1882 – Reaches Colton

Track completed to Colton; the line begins to make inroads into Southern Pacific territory. - September 13, 1883 – Main Line Opened

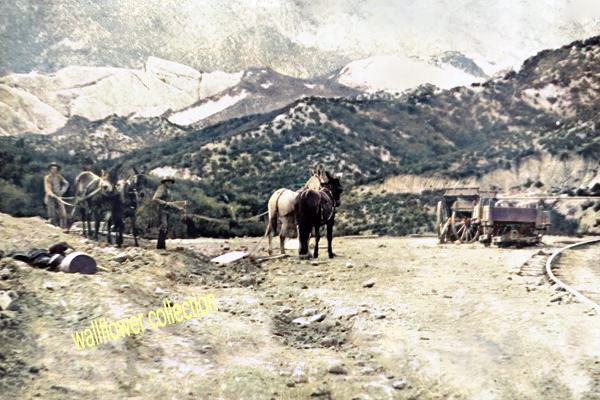

Full operation begins between San Diego and San Bernardino. California Southern faces strong opposition from the Southern Pacific almost immediately. - Winter 1883–1884 – Severe Flood Damage

Torrential rains devastate Temecula Canyon. Thirty miles of track are destroyed, bridges are washed away, and ties are seen floating far out to sea. The company faces ruin unless major repairs are undertaken. - Early 1884 – Strategic Setback

Southern Pacific, exercising influence over the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, forces the eastern connection to be built at Needles on the Colorado River—far beyond the original plan—meaning California Southern must now cross 300 miles of mountain and desert. - Mid-1884 – Threat of Independent Construction

In response, the California Southern and Atlantic and Pacific announce that if necessary, they will build a completely independent railroad across the desert to avoid using Southern Pacific lines. Surveys are ordered, and eastern backers prepare financing. - October 1884 – Southern Pacific Relents

Rather than risk parallel competition, the Southern Pacific agrees to sell the Needles-to-Mojave line to the California Southern Railroad. The Pacific Improvement Company, an entity under the control of Southern Pacific, had built the track. - November 1885 – Line Repaired and Completed

After extensive repairs and new construction, the California Southern opens through service from San Diego to Barstow, near the junction of the Atlantic and Pacific at Needles. - October 1886 – Control Transferred to Santa Fe

The California Southern is formally absorbed into the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway system, becoming part of a major transcontinental route and ending Southern Pacific’s near-monopoly over southern California rail traffic.

The struggles and ultimate success of the California Southern Railroad marked a turning point in the history of Southern California. By securing a route independent of the Southern Pacific’s control, the California Southern, under the wing of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe, opened the region to competition, lower freight rates, and new waves of settlement and development.

No longer isolated or captive to a single powerful railroad, San Diego and the inland valleys could now connect directly to the markets of the East. The great deserts and mountains that had once seemed impassable barriers became corridors of commerce and migration. In many ways, the hard-fought efforts of the California Southern and its allies helped lay the groundwork for the explosive growth of Southern California that would follow in the decades to come. It was a victory not only of rails and capital, but of determination against monopoly and geographic hardship.