Founding Figures and Early Land Purchases

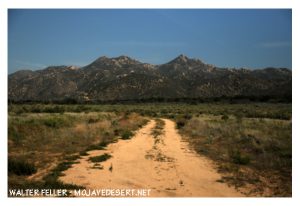

The Hesperia Land and Water Company was established during Southern California’s great land boom of the mid-1880s. In 1885, Dr. Joseph P. Widney – a prominent Los Angeles figure and former president of USC – joined with his brother, Judge Robert M. Widney, and the Chaffey brothers (George and William Chaffey, renowned for developing Ontario, California) to form the company. That year, Joseph Widney acquired approximately 35,000 acres of Mojave Desert land (previously assembled by Max Strobel in 1869–1870) and laid out a townsite for a new colony. They named the settlement “Hesperia,” derived from a Greek term meaning “western land,” which reflected its location at the western edge of the desert.

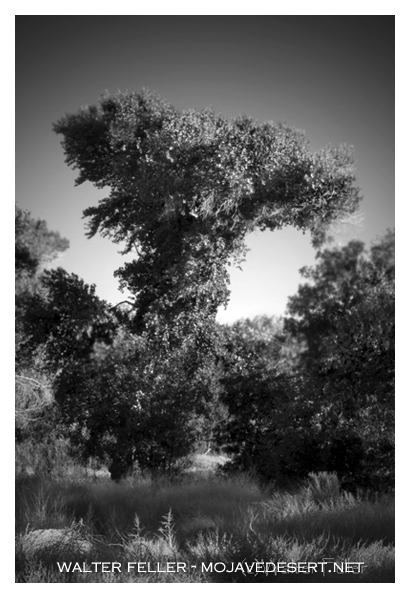

The town plan featured broad streets – reportedly laid out in a grid with unusually wide rights-of-way, lined with shade trees – as part of an envisioned modern desert utopia. The initial tract included most of Township 4 North and parts of 5 North, Range 4 West, spanning the Mojave River’s west mesa and upper valley.

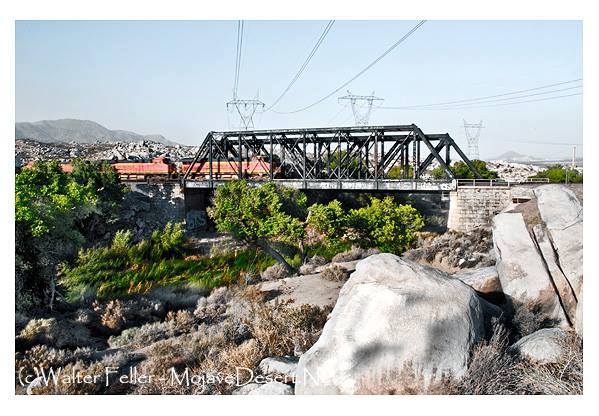

Early on, the developers sold about 2,000 acres (including a strategic dam site at the Upper Mojave Narrows) to help start the adjacent railroad town of Victor (Victorville), while reserving the mesa lands for Hesperia’s development. By late 1885 the California Southern Railroad (Santa Fe) had completed its line up through the Cajon Pass, and a small depot at Hesperia was in service, positioning the area for incoming settlers and tourists.

Development of the Hesperia Irrigation System and Water Rights

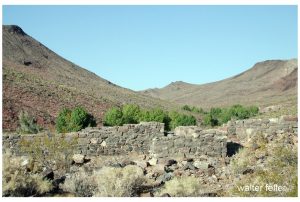

Securing a reliable water supply was crucial to the colony’s agricultural ambitions. In early 1886, the company staked an ambitious claim to the flows of Deep Creek (the east fork of the Mojave River). Following frontier water law, Hesperia Land & Water placed a stone monument on the creek in 1886 to give public notice of its appropriation: an enormous 5,000 miner’s inches of water (per minute) to be diverted for use on the Hesperia lands. This volume, equivalent to around 125 cubic feet per second, was touted as enough water for tens of thousands of people, far anticipating the needs of the few settlers then present. The claim, which accounted for virtually all of Deep Creek’s flow, was intended to ensure Hesperia’s future growth and establish priority over downstream users. Indeed, the filing for 5,000 miner’s inches in 1886 would become the basis of Hesperia’s water rights for decades, and the company later asserted that it had continuously used this water each year for 20 years – thereby “proving up” its rights. The initial water works, begun in 1887, were hailed as a marvel of engineering: the so-called Hesperia Ditch and pipeline system. Engineers excavated a diversion channel in solid rock high in Deep Creek Canyon and built a diversion dam and intake above the Forks (where Deep Creek joins the West Fork Mojave). From there, water was carried about four miles in an open, concrete-lined canal along the canyon wall. At the Mojave River, the flow dropped into an inverted siphon – a 14-inch diameter riveted steel pipeline that ran 1¼ miles under the riverbed and up the opposite side to the Hesperia Mesa. The pipeline then extended several more miles across the mesa, totaling five miles of pipe, and emptied into an earthen reservoir near today’s Lime Street (this reservoir had a capacity of about 58 acre-feet). By 1888, the Hesperia irrigation system was operational, capable of delivering roughly 40 second-feet of water to the mesa. The colony used the water to plant orchards (notably apples) and other crops; at peak in the late 1880s, about 1,000 acres of farmland in Hesperia were under irrigation from this system.

Securing the water was not without conflict. Almost as soon as Hesperia’s plans became known, farmers and landowners downstream along the Mojave River (in Victorville, Oro Grande, and beyond) objected strenuously to this large upstream diversion. They feared Hesperia’s ditch would diminish the Mojave’s flow that sustained their ranches. Legal challenges and threats were raised even “before a spade was turned”, but Robert Widney and his company pressed ahead regardless. The Hesperia canal was completed and water was flowing by 1888, despite the protests. However, the dispute over Deep Creek water rights simmered and would resurface in later years. Hesperia’s appropriation was recorded with San Bernardino County and stood as a senior claim. Still, competing schemes would test it, most dramatically the Arrowhead Reservoir project in the early 1900s (discussed below) that aimed to impound the headwaters for use outside the desert.

Town Promotion, the Hesperia Hotel, and Railroad Connections

The Hesperia Land and Water Company undertook energetic promotional efforts to attract buyers and settlers to their desert colony. As a centerpiece of the development, the company constructed the grand Hesperia Hotel in 1887. This was a three-story, 36-room hotel built of adobe bricks (freighted in from Oro Grande), then painted a distinctive red. The hotel was intended to serve as both comfortable lodging for prospective land purchasers and a resort destination in its own right, capitalizing on the desert climate and scenery. Promotional literature described Hesperia as a healthful, idyllic community where irrigation would “make the desert bloom.” Wide, tree-lined streets and a planned town center were mapped out, and the availability of ample water for homes and farms was heavily advertised. Excursion trips were likely arranged, as the new railroad line made Hesperia accessible from Los Angeles and San Bernardino. Indeed, by 1885, the California Southern Railroad (part of Santa Fe) had established a station at Hesperia, which became a regular stop along the line through the Victor Valley. This rail connection was crucial in bringing in investors during the boom. The company also laid out a small business district near the station and hotel, anticipating an influx of commerce. By 1890, Hesperia boasted not only the hotel but also a general store, a post office, and a schoolhouse to serve the nascent community. All of these improvements were in place just as Southern California’s speculative land frenzy was reaching its zenith. For a brief moment, Hesperia appeared poised to become a thriving agricultural colony and tourist retreat in the high desert.

Collapse in the 1887–1888 Land Bust

Hesperia’s boom was short-lived. In 1887, the inflated real estate market across Southern California abruptly crashed, bringing land sales to a standstill. The grand plans of the Hesperia Land and Water Company began unraveling almost immediately after the costly infrastructure was built. By mid-1888 – barely six months after the hotel and other facilities were finished – the regional land boom went “bust,” and demand for Hesperia lots evaporated. Many of the investors and would-be settlers simply never arrived, leaving the new town with a handful of residents and far more lots than people. The company, having expended enormous capital on land, waterworks, and the hotel, found itself unable to generate revenue. A general economic depression particularly affected land development companies in the late 1880s, and Hesperia was no exception. The ambitious irrigation system that had been Hesperia’s pride became a financial liability, expensive to maintain with too few customers paying for water. In the 1890s, cultivated acreage shrank significantly as orchards and fields were abandoned due to a lack of farmers. The Hesperia Hotel, once a showpiece, largely stood empty; it survived into the 20th century but never fulfilled its original purpose as a luxury resort. Contemporary accounts began referring to Hesperia as a “ghost town” – a fate sealed by the collapse of the 1880s land boom. The Hesperia Land and Water Company itself slid toward insolvency. It made no further progress on expanding irrigation and could not finance crucial improvements like a storage reservoir to capture winter flows (needed to ensure summer water supply). Periodic flash floods even damaged the pipeline – the steel siphon under the Mojave River was washed out several times around the turn of the century. By 1909, the system had temporarily ceased delivering water to Hesperia. Essentially, the Grand Desert Colony project lay dormant and failed as a private venture, awaiting reorganization.

James G. Howland’s Role in Hesperia’s Early History

One name often mentioned in local reminiscences of early Hesperia is James G. Howland. Although not listed among the original incorporators, Howland appears to have been a key leader on the ground during the colony’s formative years. Contemporary reports and later historical sketches suggest that James G. Howland acted in a managerial or executive capacity for the Hesperia Land and Water Company, overseeing daily operations and promotion of the townsite. Some accounts refer to Howland as effectively leading the company’s efforts in Hesperia – for example, directing the sales campaign and perhaps supervising the construction of the infrastructure. Dr. Joseph Widney and the Chaffeys provided the vision and capital, but it was figures like Howland who carried out the practical development work. Howland’s background is less documented in published sources; he may have been an associate of the Chaffeys or an experienced land agent hired to manage the Hesperia project. By local lore, he was the “resident booster” for the town, responsible for guiding tours of the property and extolling the new colony’s potential. Archival information on Howland is sparse, but it’s known that he remained involved at least until the collapse of 1888. After the land bust, Howland fades from the record – it’s unclear whether he stayed on the desert or moved to other ventures. Nonetheless, his early leadership in Hesperia earned him a spot in the town’s historical memory. Modern historical summaries credit Howland as having “led” the Hesperia Land and Water Co.’s promotional push, even if his name did not appear in official founder lists. He is an example of the many 19th-century development promoters whose work was critical to these boomtown schemes, even if later overshadowed by the marquee investors. (Further biographical details on James G. Howland have proven elusive in available archives, suggesting that dedicated research in regional archives or newspapers might be needed to flesh out his story.)

Reorganization under the Appleton Land, Water and Power Company (1911)

After two decades of stagnation, Hesperia got a second chance in the early 20th century. In 1911, the assets of the defunct Hesperia Land and Water Co. were purchased and restructured by a new investment group under the name Appleton Land, Water and Power Company. This company was essentially the successor to the original colony enterprise, formed with an authorized capital stock of $300,000 (similar to the original). The Appleton group – reportedly led by P.D. Hatch of Los Angeles – aimed to revive Hesperia’s agricultural potential and make the faltering water system viable. Upon taking over in 1911, Appleton immediately set about rehabilitating and upgrading the infrastructure. They relined the old intake canal from Deep Creek. They replaced the unreliable siphon pipeline with a brand new, larger-capacity steel pipe in a better location under the Mojave River. Specifically, approximately four miles of new 30-inch riveted steel pipe were laid, including a redesigned inverted siphon that crosses the river – a substantial improvement over the old 14-inch line.

Portions of the original pipeline leading to Hesperia were retained, but much of the system was modernized. A concrete diversion dam (20 feet long) with proper headgates was built on Deep Creek to control and measure the flow into the conduit. Through these efforts, Appleton increased the canal’s capacity to an estimated 40 cubic feet per second and aimed to bring more land under irrigation. To separate utility operations from land sales, the Hesperia Water Company was formed in 1915 as a subsidiary public service entity. With a $40,000 capital investment, the Hesperia Water Co. took over the distribution of water to local users, leasing the water rights and facilities from Appleton, and came under the regulation of the state Railroad Commission as a public utility. This move “divorced” the water service from the colonization business, recognizing that the two required different management. By 1916, however, irrigation under the revived system was still modest – only about 310 acres (90 in orchards and 220 in alfalfa and corn) were being watered. Appleton L. W. & P. Co. controlled roughly 20,000 acres of land (the bulk of the original holdings), with approximately 18,000 acres of that accessible by the new mainline pipe; however, they had not yet succeeded in attracting large numbers of settlers to purchase and farm the land. The new company continued to supply water to the neighboring town of Victorville. Notably, the Victorville water system (serving that community by the river) was owned and operated by Appleton as of the late 1910s. Despite the improvements, Hesperia’s growth continued to be slow. The Appleton company’s strategy eventually shifted more toward long-term land holding and leasing water, rather than immediate large-scale colonization. Nonetheless, the 1911 reorganization preserved Hesperia’s water rights and infrastructure for the future, preventing the project from collapsing entirely.

Legal Disputes over Deep Creek Water (Arrowhead Reservoir Company Conflict)

Hesperia’s water rights claims soon faced a serious challenge from outside interests. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, a consortium of Los Angeles and San Bernardino investors formed the Arrowhead Reservoir Company, with the intention of damming Deep Creek (and other headwaters in the San Bernardino Mountains) to divert water southward to the growing cities of the San Bernardino Valley. This plan directly threatened the Mojave Desert communities because it would have siphoned off the source of the Mojave River. Starting around 1902, a prolonged legal and political battle unfolded between Arrowhead Reservoir Co. and virtually all Mojave River water users, prominently including the Hesperia Land and Water Co. and its successors. W.A. Field, who was president of Hesperia Land & Water around this time, led the fight on behalf of the desert interests. Hesperia’s position was that its prior appropriation and use of Deep Creek (dating back to 1886) gave it a superior right that would be harmed if Arrowhead built its dam. In formal filings and court actions, Field and the company argued that the Arrowhead project would “deplete, obstruct or eradicate” the natural flow of water into the Mojave River, thereby violating Hesperia’s vested rights and devastating the farms that depended on that water. The Hesperia company asserted control over some 33,000 acres along the river and marshaled evidence of its water claims: notably a filing for 1,000,000 miner’s inches of flood flow on both forks of the Mojave (an enormous claim made in the early 1900s to preempt Arrowhead). Hesperia pointed out that its claim predated Arrowhead’s by over two years, and furthermore, that for 20 years it had continuously taken about 5,000 miner’s inches from Deep Creek for use on the Hesperia mesa, establishing an “inviolable right” through continued beneficial use. In 1906, while Arrowhead Reservoir Co. began constructing a dam at Little Bear Valley (what would become Lake Arrowhead), Hesperia’s allies (including other ranchers and a group of midwestern investors who had bought up downstream rights) prepared to build a dam of their own in Victor Valley to capture water for local use. A flurry of lawsuits ensued. In 1909, numerous riparian landowners in the Mojave River basin – bolstered by Hesperia’s claims – filed suit to enjoin Arrowhead from diverting the mountain waters out of the basin. These cases dragged on for years. Ultimately, the desert interests prevailed: Arrowhead’s scheme to export Mojave water was halted. By the time Arrowhead’s dam (Lake Arrowhead) was completed in 1922, it was for recreational and local use only; the courts had prohibited the company from sending water south to San Bernardino. The precious Deep Creek flows continued down into the Mojave River, securing the water supply for Hesperia and its neighbors. This protracted legal victory was significant – it protected the Victor Valley’s lifeline and affirmed the priority of Hesperia’s 19th-century water appropriation. Decades later, those same rights would be recognized in comprehensive water adjudications for the Mojave Desert.

Long-Term Influence on Hesperia and the Victor Valley

Though the Hesperia Land and Water Company’s original venture did not immediately blossom into the thriving colony its founders envisioned, it left a lasting imprint on the High Desert’s development. The town of Hesperia itself survived in diminished form – a “ghost that refuses to die,” as one historian later put it – thanks largely to the water infrastructure and land surveys put in place in the 1880s. The wide streets laid out by Widney and the Chaffeys became the skeleton of the Hesperia community that would finally grow many decades later. Most importantly, the company’s early establishment of water rights on Deep Creek ensured that Hesperia and surrounding areas had a secured share of water for future use. This proved crucial for the valley’s long-term viability. The successful defense against the Arrowhead Reservoir diversion preserved the Mojave River flows for local agriculture and settlement through the 20th century. Communities like Victorville and Apple Valley thus continued to have access to water, allowing them to expand. In fact, the Hesperia project indirectly spurred development elsewhere in the Victor Valley: for example, in the 1890s some of Hesperia’s unused land was planted in vineyards, producing raisins and wine that briefly gave the Hesperia name a positive reputation. The idea of desert land reclamation persisted – Appleton Land & Water Co.’s efforts in the 1910s to grow apples and alfalfa in Hesperia were an outgrowth of the original dream. While those early orchards never reached large scale, they demonstrated the desert’s agricultural potential under irrigation.

In the long run, the greatest impact of the Hesperia Land and Water Company was to anchor a settlement at the top of the Cajon Pass that could later be revived. Indeed, after World War II, the Victor Valley experienced a new land boom. In 1954, the remaining 35,000-acre Hesperia ranch (still essentially the same tract the Widneys had assembled) was sold to a development syndicate, the Hesperia Land Development Company. This mid-20th century effort, building on the old townsite and water system, finally succeeded in sparking substantial growth. By the late 1950s, Hesperia was marketing itself as an affordable residential community for Southern Californians, and population began rising. The city of Hesperia incorporated in 1988, a milestone that would have been impossible without the foundations laid by the 1885 company. The influence of that original company is also evident in the region’s infrastructure: the general route of today’s water deliveries in Hesperia traces back to the Deep Creek diversion engineered in the 1880s. The Victor Valley’s agricultural and urban development throughout the 20th century – from ranches to suburbs – was enabled by the water rights and pioneering spirit of those early entrepreneurs. In sum, the Hesperia Land and Water Company’s ambitious attempt to “make the desert bloom” did not prosper on the first try, but it set in motion the land acquisitions, legal rights, and vision of a desert community that eventually became reality. Hesperia and its neighboring High Desert towns owe a considerable debt to that 1880s boom-era venture for establishing their place on the map and securing the water that sustains them to this day.

Sources: Historical records and analyses were drawn from local history publications, engineering reports, and archival documents, including the State of California Dept. of Engineering Bulletin No. 5 (1918) on Mojave River irrigation, Edmund Jaeger’s “The Ghost that Refuses to Die” (Desert Magazine, Aug. 1954), San Bernardino County historical chronicles, and contemporary accounts and legal filings regarding water rights (e.g. Van Slyke v. Arrowhead Reservoir Co., 1909). Newspaper archives and local museum materials corroborate the roles of key figures like the Widneys, Chaffey brothers, and James G. Howland in Hesperia’s founding. The city of Hesperia’s own historical overview and marker texts were also consulted for confirmation of dates and figures.

regarding recommendation from New England of another engineer-bridge

regarding recommendation from New England of another engineer-bridge