The controversy over John Brown’s toll road through Cajon Pass in the mid-19th century revolved around money, fairness, and public access—a classic tension in frontier development.

1. Brown’s Toll Road and Franchise Rights

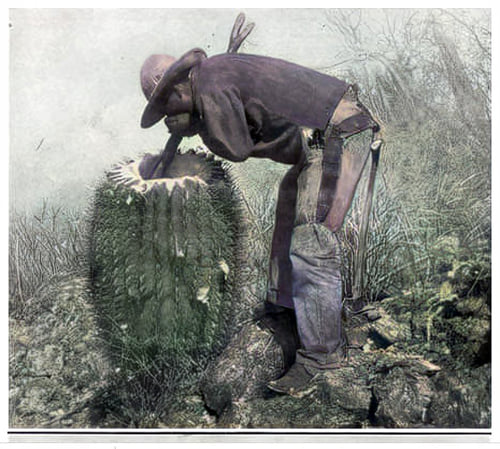

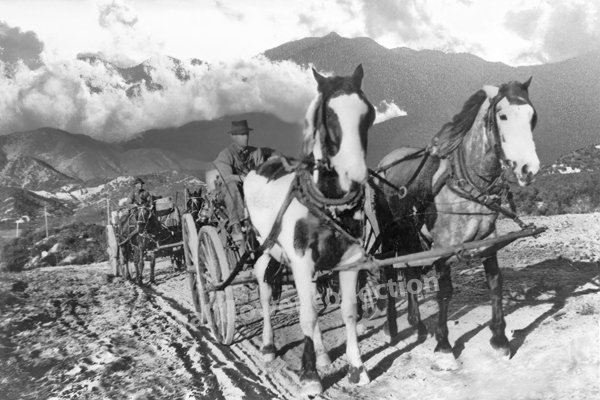

In 1861, San Bernardino County granted John Brown Sr. and his partners a franchise to build a toll road through Cajon Pass, a vital route connecting San Bernardino Valley to the Mojave Desert and beyond. They improved the existing wagon trail—grading it, clearing rock, and making it more passable for wagons—and charged tolls to those using it.

2. Public Frustration

While the improvements were appreciated, some settlers and freighters grumbled about the tolls. The road served as a major conduit for travel and trade; paying a toll on what many viewed as a natural thoroughfare didn’t sit well with everyone. The sentiment grew that Brown was profiting off a public necessity.

3. Competing Routes and Free Road Advocates

As traffic increased, alternate routes began to be explored, especially by those who wanted to avoid tolls. There were also pushes from the community and local government to establish a public road that would be toll-free. Some even attempted to create alternate trails that bypassed the toll gates, fueling the controversy.

4. Political Wrangling

Brown’s toll franchise became entangled in local politics, with supporters arguing it encouraged development and opponents seeing it as a private monopoly over a public passage. This debate sometimes reached county supervisors, and there were calls to revoke or revise the franchise.

5. Toll Road Decline

Eventually, as public roads improved and more options became available, the toll road’s importance faded. It’s unclear exactly when tolls stopped, but free passage eventually became the norm, and the road was absorbed into the public road system.

In short, the controversy was over the balance between private investment and public access, a theme repeated throughout Western expansion. John Brown wasn’t alone—toll roads were common in the 1800s—but he was one of the more talked-about due to its location and importance.

also see: