Historical Timeline

Pre-1800s: Long before any prospectors showed up, the Mojave River Valley was home to Native people — mostly Serrano and Vanyume — who used the river as a trade route and a life source, traveling and trading across the desert.

1852: The earliest known burial took place at what would become the Oro Grande Cemetery, making it one of the oldest cemeteries in San Bernardino County. Some believe it also holds the remains of earlier Native residents.

1858: Army veteran Aaron G. Lane settled along the Mojave River and opened a ranch and store for travelers. This spot, known as Lane’s Crossing, became one of the first American settlements in the region.

1865: Lane sold his original ranch and moved farther down the river to establish another at Bryman. Still, the old crossing remained a key stop for migrants, traders, and freighters heading east or west.

1873: A gold discovery on Silver Mountain drew in prospectors and gave birth to the Silver Mountain Mining District. Miners rushed to the area, and a little desert mining boom began.

1880: More gold and silver were found nearby, and the Red Mountain District was formed. Around this time, the town of Oro Grande got its start, named after the “big gold” — the Oro Grande Mine.

1881: A post office was opened under the name Halleck, showing that the settlement had grown enough to need regular mail service.

1887: Limestone was discovered in the hills near town, and small-scale quarrying began. Two kilns were built to turn limestone into lime, laying the groundwork for the cement industry.

1907: The Riverside Cement Company opened its plant in Oro Grande, and that changed everything. Cement production became the town’s main industry — and much of it went toward building Route 66.

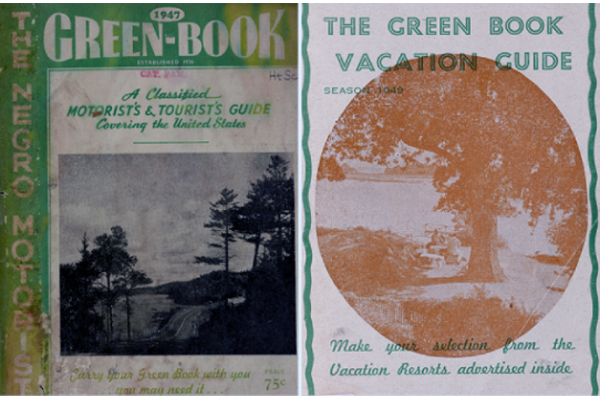

1926: Route 66 officially rolled through Oro Grande, following the old National Old Trails Highway. The town saw a new wave of business thanks to passing motorists, truckers, and tourists.

1927: The post office finally changed its name from Halleck to Oro Grande, matching the town’s identity.

1958: When Interstate 15 was built, it bypassed Oro Grande. With fewer people passing through, many roadside businesses began to fade.

2023: San Bernardino County Museum designated the Oro Grande Cemetery as a historic site, recognizing its importance and planning for its preservation.

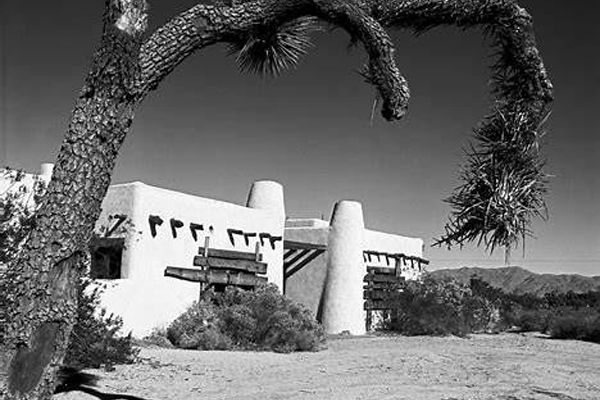

Present Day: Oro Grande is still a quiet community along the Mojave River. The old cement plant still runs, and roadside landmarks like Elmer’s Bottle Tree Ranch keep Route 66 travelers stopping by. The town wears its history proudly — a mix of mining dreams, industrial grit, and desert charm.

Pre-1800s: Long before any prospectors showed up, the Mojave River Valley was home to Native people — mostly Serrano and Vanyume — who used the river as a trade route and a life source, traveling and trading across the desert.

1852: The earliest known burial took place at what would become the Oro Grande Cemetery, making it one of the oldest cemeteries in San Bernardino County. Some believe it also holds the remains of earlier Native residents.

1858: Army veteran Aaron G. Lane settled along the Mojave River and opened a ranch and store for travelers. This spot, known as Lane’s Crossing, became one of the first American settlements in the region.

1865: Lane sold his original ranch and moved farther down the river to establish another at Bryman. Still, the old crossing remained a key stop for migrants, traders, and freighters heading east or west.

1873: A gold discovery on Silver Mountain drew in prospectors and gave birth to the Silver Mountain Mining District. Miners rushed to the area, and a little desert mining boom began.

1880: More gold and silver were found nearby, and the Red Mountain District was formed. Around this time, the town of Oro Grande got its start, named after the “big gold” — the Oro Grande Mine.

1881: A post office was opened under the name Halleck, showing that the settlement had grown enough to need regular mail service.

1887: Limestone was discovered in the hills near town, and small-scale quarrying began. Two kilns were built to turn limestone into lime, laying the groundwork for the cement industry.

1907: The Riverside Cement Company opened its plant in Oro Grande, and that changed everything. Cement production became the town’s main industry — and much of it went toward building Route 66.

1926: Route 66 officially rolled through Oro Grande, following the old National Old Trails Highway. The town saw a new wave of business thanks to passing motorists, truckers, and tourists.

1927: The post office finally changed its name from Halleck to Oro Grande, matching the town’s identity.

1958: When Interstate 15 was built, it bypassed Oro Grande. With fewer people passing through, many roadside businesses began to fade.

2023: San Bernardino County Museum designated the Oro Grande Cemetery as a historic site, recognizing its importance and planning for its preservation.

Present Day: Oro Grande is still a quiet community along the Mojave River. The old cement plant still runs, and roadside landmarks like Elmer’s Bottle Tree Ranch keep Route 66 travelers stopping by. The town wears its history proudly — a mix of mining dreams, industrial grit, and desert charm.