The Road, the Valley, the City, and the Range

Tucked between the Inyo Mountains and the Panamint Range in eastern California lies Panamint Valley—a vast, arid stretch of desert where stories cling to the rocks and dust. Part of the northern Mojave Desert, this remote basin has seen centuries of human presence, from Native American trade routes and outlaw hideouts to a silver mining boom and military testing. Surprise Canyon is at the heart of this tale, a rugged cut through the mountains that once served as both a refuge and a gateway to fortune.

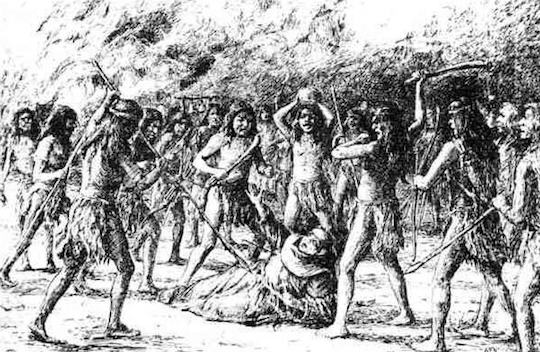

Native Roots and Early Exploration For thousands of years, the Timbisha Shoshone and other Native American groups lived in and around Panamint Valley. They followed game, gathered plants, and knew the subtle signs of water in this harsh landscape. Early explorers and pioneers during the California Gold Rush would later follow their trails. However, few stayed long in the face of the valley heat, dryness, and isolation.

Outlaws in Surprise Canyon In early 1873, three men hiding from the law—William L. Kennedy, Robert L. Stewart, and Richard C. Jacobs—discovered silver in the steep, narrow depths of Surprise Canyon. Some say they were drawn there by rumors of the Lost Gunsight Mine. Regardless, they struck it rich. Sources differ on the exact date: Nadeau places it in January, Wilson in February, and Chalfant in April. But by June, prospectors had filed 80 claims, and the ore was assaying at thousands of dollars per ton.

Big Money and Bigger Names Enter E. P. Raines, who secured a bond on some of the most promising claims and began promoting the new district. He drew attention by hauling a half-ton block of silver ore to Los Angeles and displaying it at the Clarendon Hotel. This bold stunt brought together jewelers, bankers, and freighters, who agreed to build a wagon road to the mines. Raines continued north to San Francisco and then Washington, D.C., where he met Senator John P. Jones of Nevada, a former Comstock miner and hero of a deadly fire. Jones loaned him $15,000 and soon partnered with fellow “Silver Senator” William M. Stewart to form the Panamint Mining Company.

The senators spent over $350,000 acquiring prime claims from known Wells Fargo robbers. Senator Stewart arranged amnesty for these men, with the condition that $12,000 in profits be paid to the express company as restitution. It is believed this arrangement convinced Wells Fargo to avoid opening an office in Panamint.

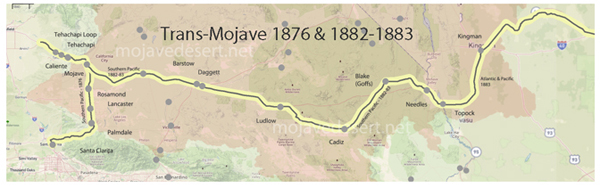

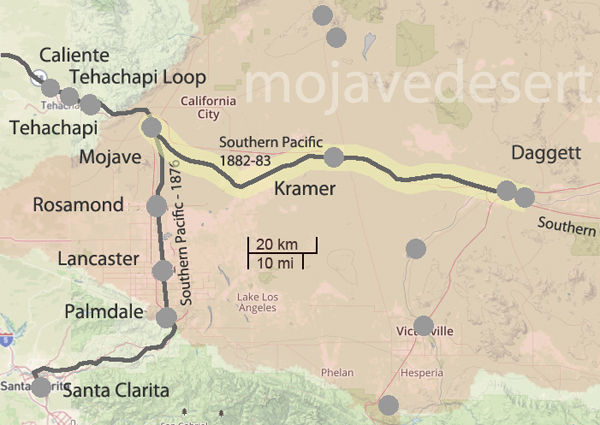

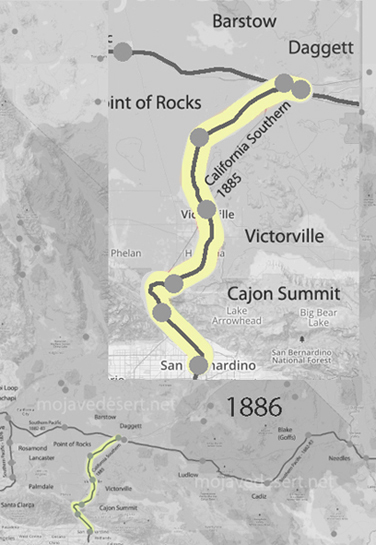

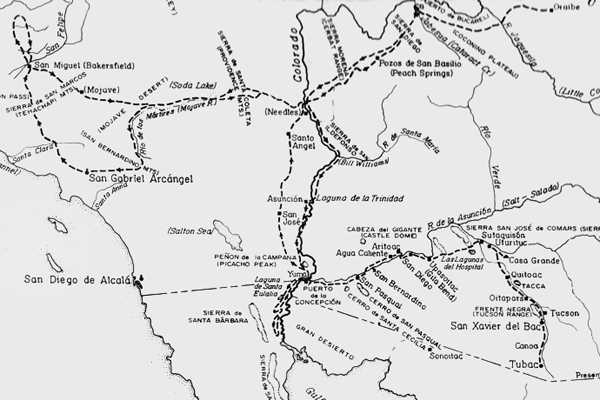

The Road to the Panamint Mines The silver rush in Surprise Canyon prompted the search for a better supply route. Senator Stewart noticed Meyerstein & Co., a San Bernardino firm, was already sending goods to the region. He encouraged Caesar Meyerstein to establish a stage line. In the fall of 1874, preparations began on a road from Cottonwoods on the Mojave River to the Panamints.

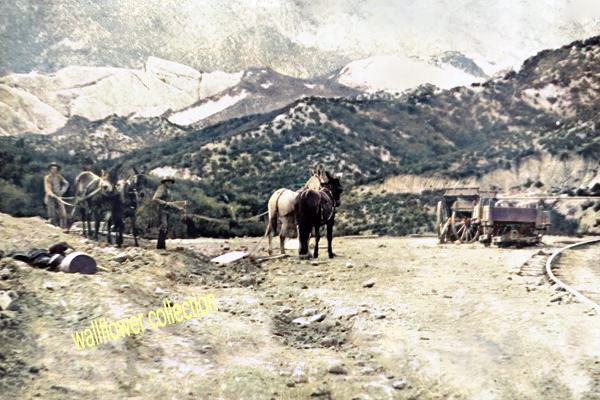

The Board of Supervisors appointed Aaron Lane as road overseer of the newly formed Mojave District. Lane hired a crew of Chinese laborers under foreman Charley Craw to begin construction. Miners objected to using Chinese labor, but Lane completed the project by mid-November. He advertised the route as an “excellent” road, and the Guardian praised the veteran for his work. Lane submitted a bill for $645.61, but the county approved only $500—a modest sum for 115 miles of desert road.

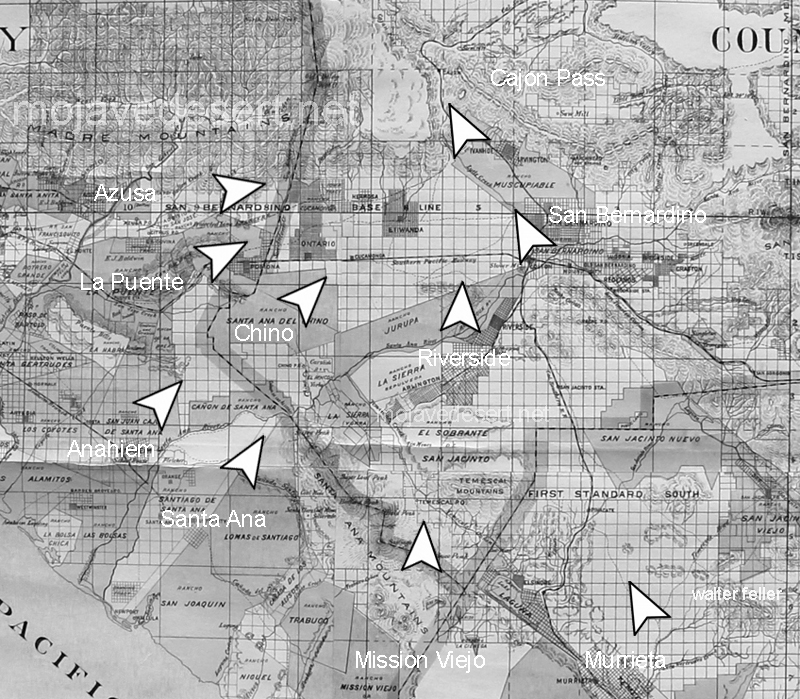

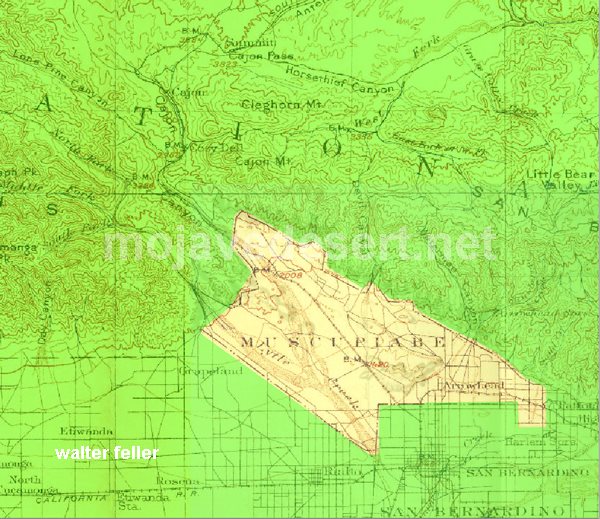

This San Bernardino-Panamint Road, sometimes called the Meyerstein Road or Nadeau Cut-Off, shortened the journey to the mines by cutting across from Cajon Pass through Victorville and Hodge (Cottonwoods), connecting with the Stoddard’s Well Road. While freighter Remi Nadeau operated the Los Angeles to Panamint route via Tejon Pass, the San Bernardino route originated separately. Despite the confusion in some sources, the Chinese labor used on the San Bernardino-Panamint Road under Captain Lane should not be mistaken for labor on Nadeau’s route.

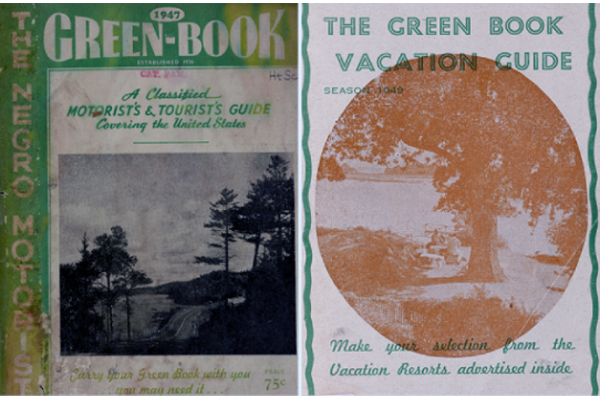

According to the San Bernardino Weekly Argus, stops along the Meyerstein route included Meyerstein to Martin’s, Fears in Cajon Pass, Huntington’s (Victorville), Cottonwoods (Hodge), Wells, Second Crossing of the Mojave, Black’s Ranch, Granite, Willow Tree Station, and finally Post Office Springs, just before reaching Panamint. These links formed a vital corridor to one of the West’s wildest boomtowns.

The Rise of Panamint City By March 1874, Panamint had around 125 residents. It had no schoolhouse, church, jail, or hospital—and it never would. To avoid robbery on the lawless route to market, the senators cast silver into 450-pound “cannonballs” that could be hauled unguarded to Los Angeles. On November 28, the Idaho Panamint Silver Mining Company was formed with $5 million in capital, followed by the Maryland of Panamint and several others with an additional $42 million by year’s end. That same month, the Panamint News began publishing—though its editor fled town within days after stealing advertising revenue.

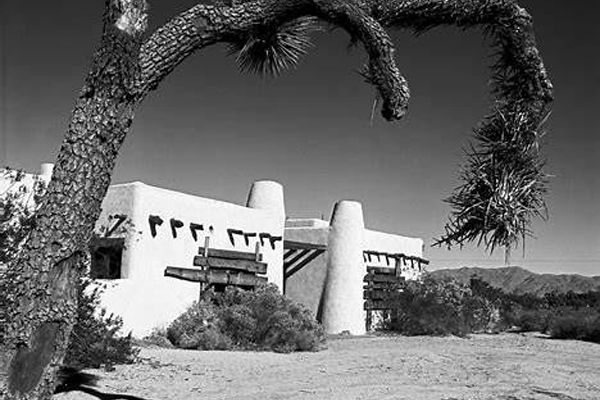

The town boomed. The winter of 1874-75 was its peak. Two stage lines operated, the Bank of Panamint opened, and 50 buildings lined Surprise Canyon. The Oriental Saloon claimed to be the finest outside San Francisco. Mules and burros were the main form of transport. The lone wagon doubled as a meat hauler and a hearse.

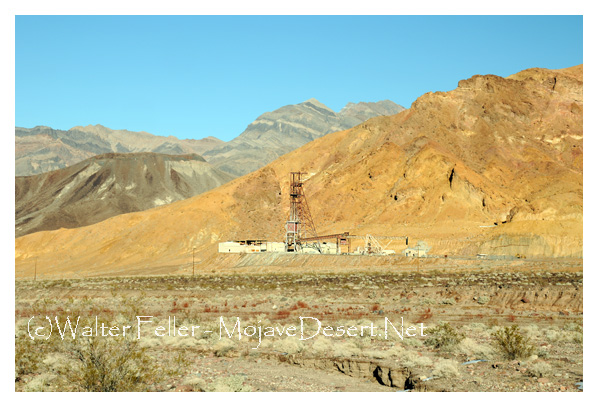

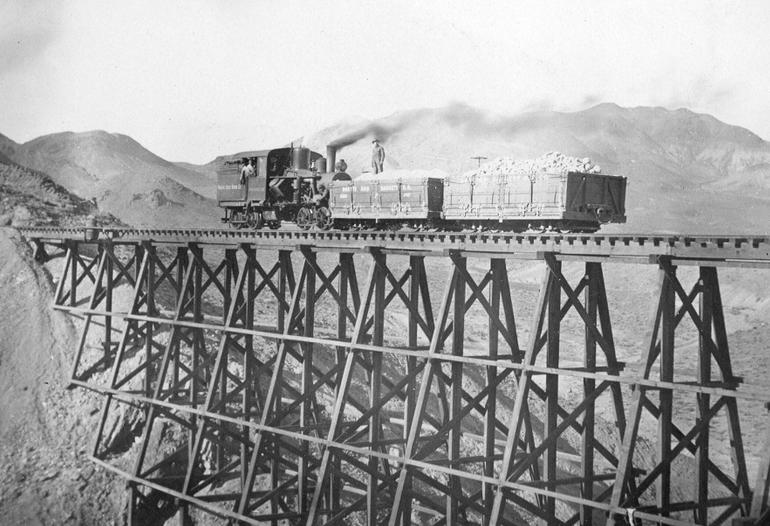

By January 1875, the population hit 1,500 to 2,000. Businesses thrived. A wire tramway sent ore from the Wyoming and Hemlock mines down to the Surprise Valley Mill and Water Company’s twenty-stamp mill. Wood costs $12 per cord, and miners earn $4 to $5.50 per day. The crumbling smokestack of this mill still stands. Daniel P. Bell, the mill’s builder, later died by suicide in Salt Lake City, reportedly after being diagnosed with cancer.

Crash and Decline Disaster came quickly. The collapse of the Bank of California in August 1875 shook confidence across the state. Panamint stock crashed, speculation dried up, and the Panamint News ceased publication. By November, the population had largely disappeared, with only a few hopefuls remaining. In July 1876, a cloudburst flooded Surprise Canyon, wiping out large sections of the town.

Senator Jones, once Panamint’s champion, held on until May 1877. But a market panic forced him to shut down the mill. Despite investing nearly two million dollars, the Silver Senators saw little return.

Later, Revivals and Post Office Spring Attempts to revive Panamint followed. Richard Decker reopened the post office during 1887 and worked claims into the 1890s. The site saw minor revivals into the 1920s and again in the 1940s. 1947-48, American Silver Corporation leased multiple claims and rebuilt the Surprise Canyon road but filed for bankruptcy in 1948. Interest returned in the 1970s, though the fractured and faulted veins proved challenging to follow.

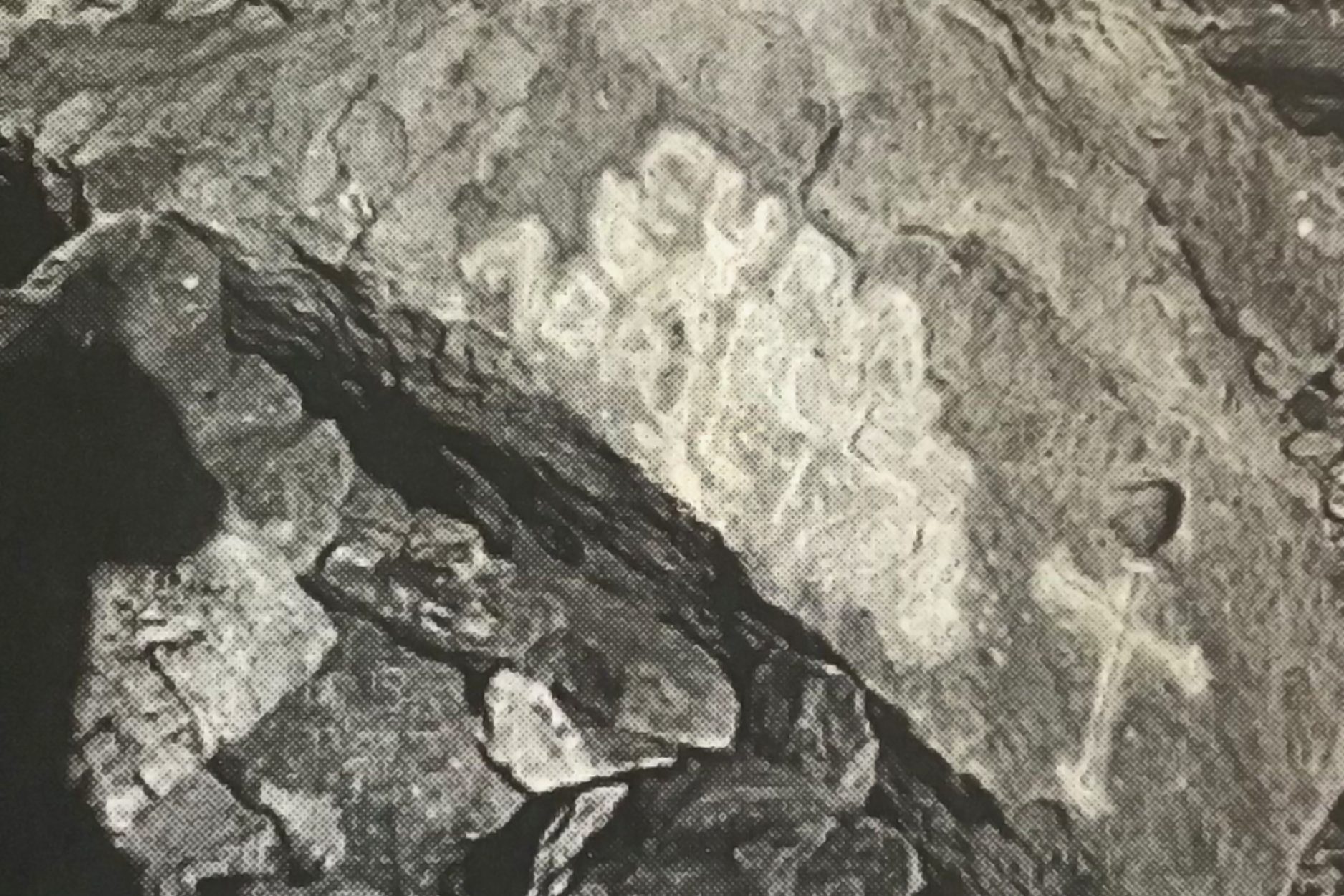

Near the city ruins, Post Office Spring played an important role. Besides being a water source, it housed a secret mail drop during Panamint’s outlaw days. A box wired to a mesquite tree held letters marked “John Doe”; a rag on a nearby branch signaled mail had arrived. At night, fugitives collected or left messages in secret.

The Panamint Range: Geology and Life The Panamint Range, separating Panamint Valley from Death Valley, rises from about 1,000 to 11,049 feet at Telescope Peak. It’s part of MLRA 29f and features Precambrian sedimentary and metamorphic bedrock, Paleozoic marine sediments (Cambrian to Carboniferous), Mesozoic granite, and Pliocene basalt. Alluvial fans spread from steep slopes into the valleys. Processes shaping the range include mass wasting, fluvial erosion, deposition, and freeze-thaw cycles.

Vegetation follows elevation, too, from creosote bush and shadscale at lower levels to pinyon, limber pine, and bristlecone forests higher up. Surface water is scarce; streams run briefly during rains and snowmelt, draining into Panamint and Death Valleys.

The Road, the Valley, the Legend The road to Panamint, first carved to bring silver to market, is now a rugged path for adventurers. Panamint Valley itself, once crossed by Native trails and mule trains, is now visited by hikers, off-roaders, and desert wanderers: the Panamint Range towers above, its silent peaks guarding the stories of a forgotten boomtown.

Panamint is more than a ghost town. It mirrors Western ambition—where silver dreams, outlaw grit, and desert extremes shaped one of the wildest chapters in California history.