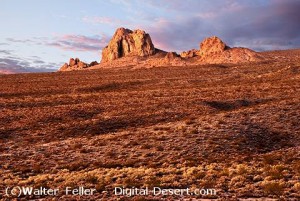

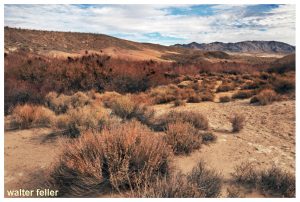

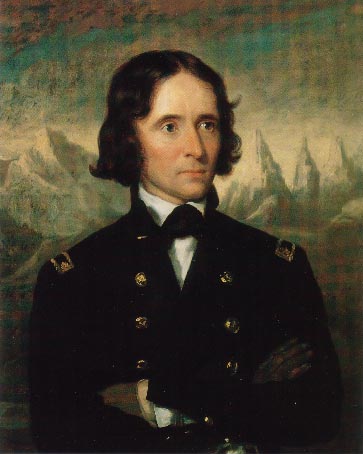

The characteristic account of the hazards of traveling through the Mojave during pioneer days appears in the journal of General John Charles Fremont. Leading a party of topographical engineers, with the famous Kit Carson and Alex Godey as scouts, Fremont was on the last leg of an exploration trip through Oregon and California, and was headed for Salt Lake City when he called camp at the lagoons 8 miles below Yermo for the purpose of killing and jerking enough beef for the long “jornada” to the next waterhole.

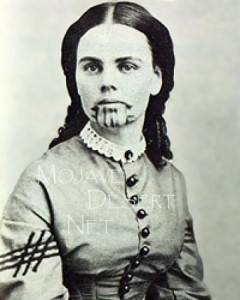

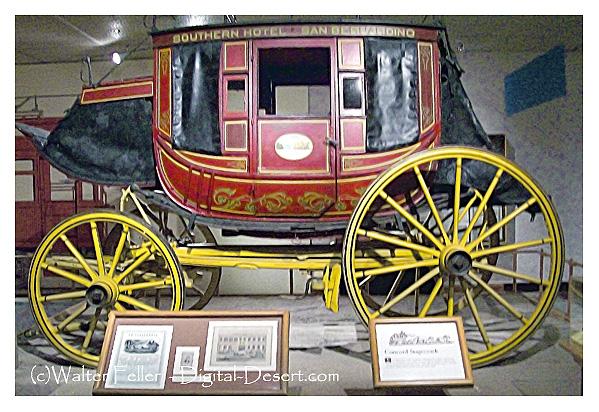

Here, on the afternoon of April 24, 1844, Fremont was surprised by the sudden appearance of two Mexicans, one a man, Andreas Fuentes, the other an 11-year-old boy named Pablo Hernandez. They were members of an advance party of six men and women who had left Los Angeles well ahead of a large caravan, in order that they might travel leisurely with their head of 30 horses. They had reached Agua Archilette (now Resting Springs) , where they decided to remain until the caravan overtook them. While camped here, they were visited by several seemingly friendly Indians. A few days after this they were surprised to see approaching them a large number of Indians, estimated to be about 100.

The commander of the Mexican party shouted to Fuentes and Pablo, who were on guard duty, to drive the horses to their former water hole. The guards were mounted according to custom and managed to stampede the horses through the Indian lines despite a volley of arrows. Knowing they would be pursued, the man and boy drove the horses about 60 miles, halting only to change mounts. When they reached Agua de Tomaso (now Bitter Springs) they left the horses there and pressed on, hoping to meet the oncoming caravan. Exhausted, the two were overjoyed to find the Fremont party.

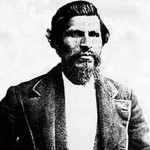

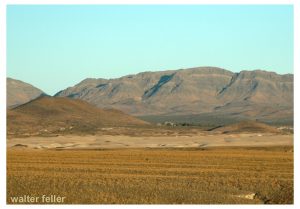

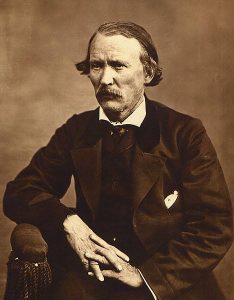

The Fremont cavalcade broke camp immediately, left the river and, turning north, followed the old Spanish trail 25 miles to Agua de Tomaso. Here they found traces of recent origin that showed the Indians had captured the horses and run off with them. Carson and Godey, accompanied by Fuentes, decided to follow the marauders. That evening, Fuentes returned alone, his horse having given out.

The scouts had been taken about 30 hours. They estimated their trip had taken them about 100 miles. At nightfall of the first day they had entered the mountains. Bright moonlight made the pursuit easy for a time, but when they entered a defile, it became necessary to dismount and feel for the trail with their hands. At midnight they lay down to sleep.

Cold as it was, they dared not to make a fire and till morning when in a little ravine, they kindled a tiny blaze to warm themselves before starting on.

At daylight they continued their pursuit and about sunrise ran across a few of the missing horses. Concealing their exhausted mounts behind a pile of rocks, they crept toward the crest of a nearby hill, from which they could look down on four lodges and about 30 Indians were gorging themselves on horse meat.

The cautious movements of the scouts disturbed a horse grazing nearby, which snorted, giving warning of their presence to the feasting Indians. The scouts charged, shouting as they went. Carson downed in the Indian with his first shot. Godey shot twice and hit another. Godey received an arrow through his shirt collar. The rest of the Indians fled, no doubt believing the two men were the advance of a large party.

Carson stood guard while Godey dashed down to scalp the two prostrate figures. As he stripped the scalp from one of them, the Indian regained consciousness and screamed. An old squaw, ascending a nearby hill, turned, hurled a handful of gravel down on Godey, and screeched maledictions. Godey mercifully killed the man. Then the scouts returned to the herd and drove it off without interference.

The scouts’ story told, Fremont ordered camp broken. The party proceeded north across the open plain. Two days later, Fremont came across the bodies of two men, Hernandez, father of Pablo, and another member of the Mexican advance party. Both had been mutilated. Later the bodies of the two women who completed the advance party were discovered, also murdered and mutilated.

adapted from ~ Pioneer Tales of San Bernardino County – WPA – 1940.