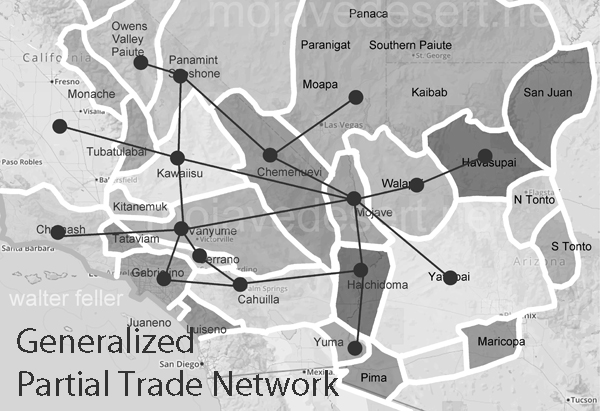

Ancient trade corridors in the Mojave Desert formed a vast network used by Native peoples for thousands of years. These routes connected water sources, villages, seasonal camps, and trade hubs, often following natural landforms like rivers, canyons, and mountain passes. Here’s a breakdown of some of the key corridors:

1. Mojave Trail (Mojave Road)

- Route: From the Colorado River near present-day Needles across the desert to Soda Lake, Marl Springs, and eventually to the Mojave River and beyond to the Cajon Pass.

- Use: Used by the Mojave (Aha Macav) and other tribes to trade shells, salt, obsidian, and other goods with coastal peoples. Later became the foundation for the Old Government Road.

2. Salt Song Trail System

- Cultural Trail: A spiritual and song-based route still remembered and sung by Paiute and Chemehuevi people. It connects sacred sites across the Mojave and Great Basin, reflecting not just trade but ceremony and storytelling.

- Route: While not a single physical path, it includes segments through valleys, springs, and mountain crossings.

3. Old Spanish Trail (Native precursor routes)

- Route: Parts of this Euro-American route followed much older Native paths from the Mojave River through the Amargosa region and toward Las Vegas and the Virgin River.

- Use: Before the Spanish established formal trade in the 1800s, Native groups had long used this corridor to exchange turquoise, basketry, and foodstuffs.

4. Owens Valley–Panamint–Death Valley Corridors

- Route: From Owens Valley south and east through the Inyo and Panamint ranges into Death Valley and beyond.

- Use: Paiute, Shoshone, and Timbisha traded pine nuts, obsidian, and other materials across this rugged terrain, often using high passes and springs.

5. Coastal–Desert Exchanges

- Route: From the Channel Islands and Chumash territories inland to the Mojave via passes like Tejon and Cajon.

- Use: Shell beads (money), fish products, and steatite were traded inland, while obsidian, pigments, and desert foods flowed west.

These trade corridors were more than just paths—they were vital lifelines that supported long-standing economies, diplomacy, migration, and ceremony. Over time, many of them were co-opted into Spanish, Mexican, and American routes, but their roots lie in much older Indigenous knowledge of the land.