by Cliff Walker

Blond-haired, whiskered veteran prospector Richard C. Jacobs and partner Bob Stewart were grubstaked by W. L. Kennedy, a Kernville merchant. Most grubstakes failed, but these two men wandered over to Panamint Valley, then up the steep 6,000-foot climb of Surprise Canyon and found several types of silver ore exposed by erosion. They made four claims, formed Panamint Mining District, and elected Bob Stewart as recorder. Samples shown to Kennedy assayed from $125 to $3,000 per ton. By April 1873, there were 80 to 90 claims. The Panamint mining started fairly normally until the search for investors brought in wealthy and influential men: two Nevada U. S. Senators, John P. Jones and William M. Stewart, and ex-49er Trenor W. Park, a New York Wall Street investor, formerly a San Francisco lawyer and current director of Pacific Mail Steamship Company and president of the Panama Railroad that linked the two oceans. Experienced in mining and investing, these successful men encouraged others to rush for quick potential riches.

Panamint Fever had started.

Miners from 29 Palms, Ivanpah, Arizona, Nevada, and northern California came to Panamint Valley and made the horrid trip up Surprise Canyon to the Panamint Mountains on a road that is still more of a dry waterfall than a road. Miners found a small booming city with sounds of hammering, dragging, and building all over, and sounds on higher hills of dynamite exploding. Anybody who wanted to work had a job at $4 per day, board $7 per week—not bad wages for those days. In March 1874 there were over 700 men who already staked about 150 claims and were still prospecting to find that great silver lode like at Virginia City. Men rented a room or a space on the ground at “Hotel de Bum,” a huge tent. Most slept outside in blankets looking at the stars.

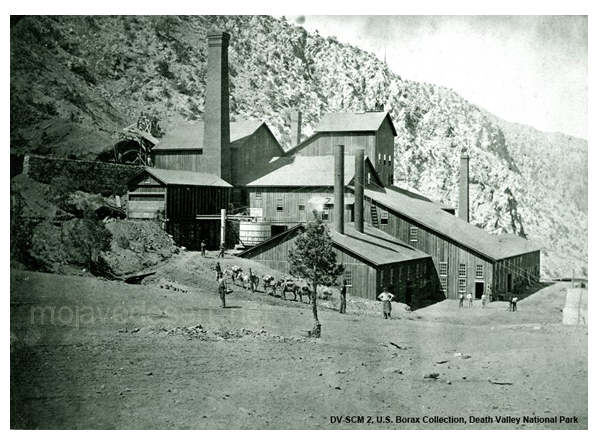

Wagons unloaded supplies at the bottom of Surprise Canyon and pack mules made it up the waterfall road, unloading their gear to tent stores, potential wooden and rock buildings, or to mines further up the hill. Jacobs hired Chinese laborers to cut down the steep grade over the Slate Range so his 10-stamp mill could be brought easily to Surprise Canyon. Owens Valley businessman Bart McGee sculptured a road up Surprise Canyon, thereby enabling wagons to use the waterfall road (where the grade was 500 feet to the mile). Seven stages a week arrived at the new city by the end of 1874.

Panamint City developed almost a mile of businesses for city amenities. According to mining historian Remi Nadeau, the city had a dozen saloons, a water company, six general stores, three bakeries and restaurants, a livery stable, boot shop, meat market, three barbershops, a newspaper called Panamint News, the Bank of Panamint, and another important town amenity: a log cabin brewery. When Martha Camp, a buxom lady from Nevada, brought her ladies to town, the night life in Panamint became livelier—it became a real city!

As usual, gamblers, criminals, gun fighters, and assuredly con-artists, climbed the hill to Panamint. The town soon needed a jail. As a result of a gambling dispute, a shootout in a saloon in which Kirby, a man from Pioche, shot Bill Norton in the leg and ran away when Norton fired back. The only official in town was town recorder W. C. Smith who discovered Kirby planned to waylay Norton. Smith got the drop on Kirby and suggested he leave town right away. The town later elected Smith Justice of the Peace. Jim Bruce and Edward Barstow, a night watchman of the town, had an argument in Camp’s house. Barstow, drinking too much, left the business but returned later after he sobered a bit and found Bruce in Martha’s bed and shot it out with Bruce. Barstow died. The town needed a cemetery.

A few years later the boom and fever ended. But the effects on the Mojave Desert was great. San Bernardino County appointed Oro Grande’s Aaron Lane as Superintendent of desert roads, namely the Road to Panamint from the Mojave River to the Inyo County line. Desert “Stations”—ranches like gas stations and motels today—were built and profited, especially with freight from San Bernardino over the Cajon Pass. For example, lumber mills in the San Bernardino Mountains supplied much of Panamint’s lumber. Berdoo merchants out- hustled L.A. businessmen. Despite Panamint’s decline in the late ’70s, mining increased in the Mojave Desert, especially with Barstow’s Waterman Mine and the wonderful Calico Hills discoveries. The Mojave Desert became settled by the end of the 1880s.

Mojave River Valley Museum Newsletter – October 2012