John Lemoigne Arrives in Death Valley

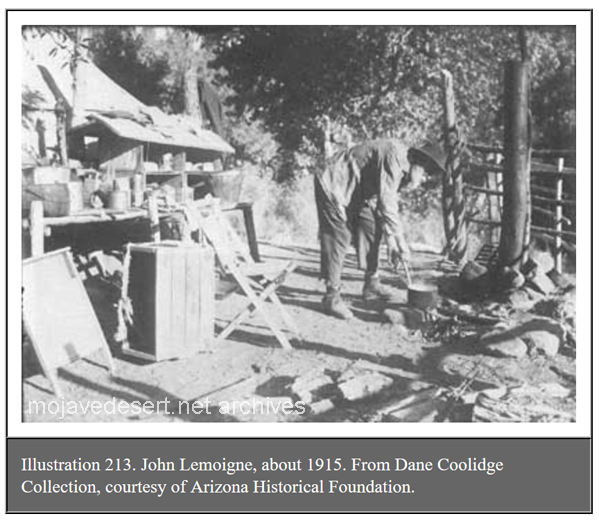

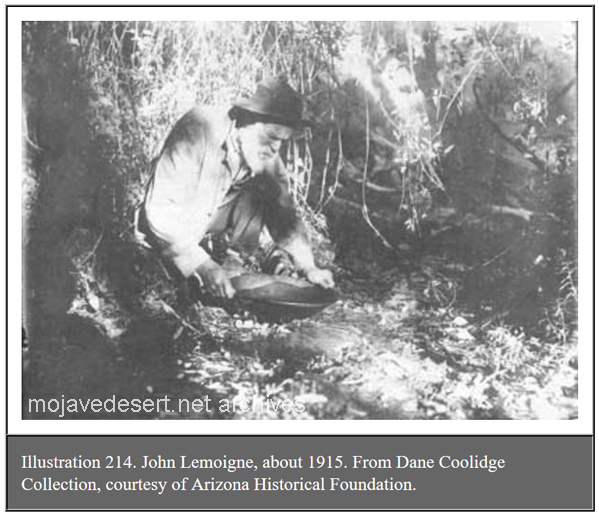

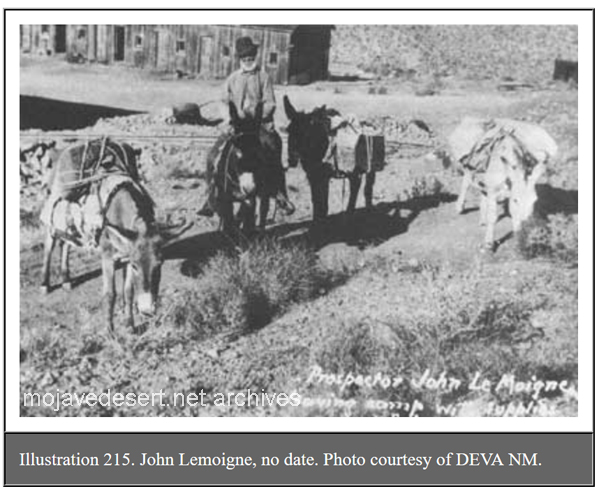

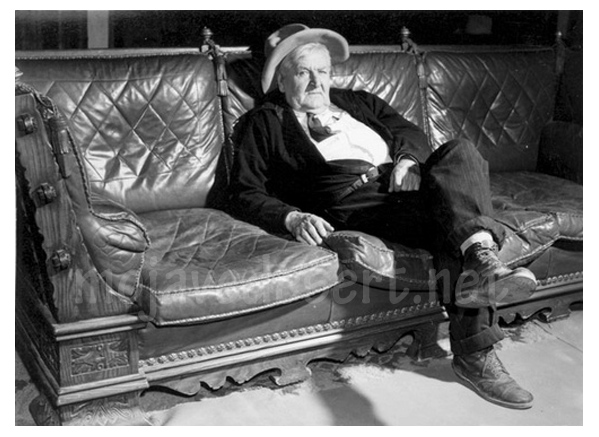

The stark, simple beauty of Death Valley has often captured the imagination and the hearts of unwary visitors and held them in its spell for their lifetime. Such an unwitting victim of this desert magic was Jean Francois de Lamoignon, born in February 1857 at Lamoignon, France, and educated in England, Paris, and Germany as a mining engineer. As seems to be the case with all Death Valley folk heroes, controversy and irreconcilable discrepancies surround every aspect of his life in the region. Initial disagreement arises over the date of the tall, white-bearded, genial Frenchman’s arrival in the Death Valley region and the impetus behind his long journey. While some sources suggest that he served as a sailor before coming to America to work in the mines around Darwin in the early 1870s, it has been most commonly assumed that he arrived here around 1882 to 1884 at the behest of Isadore Daunet, who, hearing about the young mining student through mutual friends, suggested that he take over supervision of the new borax works in the southern part of the valley (Eagle Borax Works).

By the time Lemoigne arrived in this country, however, Daunet had taken his own life, depressed by the failure of both his business venture and his recent marriage.

Once in this country, and possibly forced to stay by a lack of money, Lemoigne quickly became Americanized and acculturated, dropping his aristocratic name and donning the garb and life-style of a Death Valley prospector, although never completely losing his distinctive aura of education and intellect. Reportedly meeting some Indians in the Cottonwood area of the Panamint Range and learning from them the location of a silver-lead mine at which they fashioned bullets for their muzzle-loaders, he filed on this property, known as the Bullet Mine, about 1882, although one source stated it was not located until 1887.

Lemoigne covered a lot of territory in his peregrinations throughout the California and Nevada mining districts, prospecting from Barstow, California, east toward Virginia City and Ely, Nevada, and west toward the high Sierra Nevadas. He seems to have had fairly good luck, for his name is connected with several claims in the Death Valley region alone: the Uncle Sam Lode in the Panamint Mining District, located 11 April 1880 (which, as mentioned, would seem to imply that Lemoigne did arrive prior to Daunet’s ill-fated borax venture); the Independence, located on 14 January 1884, and the Alaska, discovered on 24 January 1884, both in the Union Mining District; the Washington, Robespierre, and Lafayette, located 28 April 1885, in the Deep Spring Mining District; and the Egle and Union mines, two relocations on 3 January 1887, and the Bullion, Stare, Hop, and Ouray, discovered 4 February 1889 in the Furnace Creek Mining District. In early 1890 Lemoigne and Richard Decker were involved together in a chloriding operation at the Hemlock Mine near old Panamint City, though five years later he was working his lead mine and talking some of erecting a smelter for his ore near Keeler. By 1896 he had filed location notices for three quartz claims in Cottonwood Canyon.

Lemoigne Properties

It is rather difficult because of the variety of locations given to determine the exact extent of Lemoigne’s holdings. His lead mine, which remained active through the 1950s, was located in present-day Lemoigne Canyon. According to Crampton, Lemoigne’s silver prospect, complete with shack, was located north of Skidoo, and it was this property that actually supported him and paid his bills and grubstakes. This is at variance with Southworth’s assertion that “He [Lemoigne] was known to depend entirely upon his highgrade silver property in Lemoigne Canyon whenever ready funds ran low.” George Pipkin states that Lemoigne opened the “LeMoigne Silver Mine at the extreme north end of the Panamint Mountains in Cottonwood Canyon,” and also discovered lead “in what is known today as LeMoigne Canyon northwest of Emigrant Springs. LeMoigne’s silver mine could have been the ‘Lost Gunsight Lode’. . .” The 1896 location notices indicate that he did have property in Cottonwood Canyon, and, indeed, evidence of mining activity was found here in 1899 where

the ruins of an old log cabin stand near to where considerable work has been done in former years by some prospectors. A large pile of lead ore lies upon the dump. Cuts have been run and shafts sunk.

In 1897 Lemoigne’s property was mentioned as one incentive for construction of a transcontinental route from Kramer Station on the Santa Fe and Pacific line to Randsburg and on to Salt Lake City that would tap the untouched mineral resources in the Panamint Valley area. It would, it was argued, facilitate shipping from the Kennedy Antimony Mine at Wild Rose, the Ubehebe copper mines, and would put within reach “the apparently inexhaustible ‘low-grade’–worth $50 per ton, with lead accounted at 54 per lb and silver at 70 per oz.–argentiferous galena ores of Cottonwood, known as the Lemoigne mines.”

In 1899 Lemoigne found a large body of high-grade lead ore on his property, but was still hindered by transportation problems and hoping for completion of a railroad into the area so that large quantities could be shipped at a profit. The lead mine was producing so well in 1904 that it was reported that Lemoigne had gone to San Francisco to negotiate its sale: “This property is said by experts to be the biggest body of lead ore ever uncovered on the coast.” Reportedly any grade of lead, up as high as 75% even, could be obtained by handsorting, the silver content varying from 15 to 83 ozs. and gold from $5 to $20. The sale was not consummated, however, and perhaps this was the basis for the oft-repeated tale of how old John, reasserting his often-voiced contempt for negotiable paper, turned down several thousand dollars for his mine because he was offered a check instead of cold hard cash.

Lemoigne was reputedly a very simple, honest man with no particular need or desire for life’s luxuries. Money was relatively unimportant and only necessary to finance his long prospecting trips or to grubstake one or another of his friends. Since it appeared that he would be returning periodically to his lead mine, Lemoigne proceeded to erect a stone cabin there. Frank Crampton recalls:

Often I stopped at the lead prospect, almost as often as at the silver prospect Old John worked, alternately with the lead [the mine near Skidoo). In the old stone cabin (house I presume might be better) he passed some of his time particularly when the weather was cold. He had built the stone house soon after he discovered the lead outcrops and realized they were good possibilities of ore. It was winter he told me when the stone house was built and water could be had from a creek bed that flowed some water. In the spring when the water either was insufficient, [sic] after his first winter at the lead prospect he went up the canyon and built himself a shack. In the shack was the shelf of classics, French, German, English, which he dusted every day and often when I remained a few days with him he would read one of them, as I did also.

Lemoigne Castle at Garlic Spring

In addition to the monetary sustenance afforded him by his mine, Old John also thrived on the goodwill of a host of fellow miners in the surrounding desert region, who considered him a gentleman and true friend. Their ready offers of food and friendship were reciprocated by John’s grubstaking offers. Sometimes this generosity brought amazing and unwelcome results.

One of the stranger stories connected with John Lemoigne and that sounds as if it might have enjoyed some slight embellishment at the hands of Frank Crampton, who first reported it, concerns a construction project at Garlic Spring on the old road between Barstow and Death Valley, where Lemoigne was camped around 1914. Two men whom he had grubstaked brought him a contract to sign, having not only located a mine but also attracted a buyer. Firm persuasion was required to secure Lemoigne’s reluctant signature on the necessary instruments, and his worst fears were soon realized when to his acute embarrassment a steady flow of grubstake profits began pouring in. Because of his strong distrust of banking institutions, Old John persuaded the local storekeeper to take charge of these funds, but that individual soon became nervous because of the large sums he was being entrusted with and the proximity of Barstow and its rough-neck railroad men and other strangers who might be tempted to avail themselves of these riches in an ungentlemanly manner.

To remedy the situation the storekeeper’s wife suggested that she be allowed to construct and furnish a large house for John in the area and thereby utilize the money. Consent was reluctantly given the lady, who proceeded to supervise the erection of “Old John’s Castle,” a monstrosity that daily grew more unwieldly and unattractive. What she lacked in expertise in architectural design and construction, she compensated for in flamboyance and general bad taste. The large, two-story square building soon sported turrets, a spire, dormer windows, gables, and a multitude of chimneys. A covered porch surrounded the bright red structure on four sides, and the whole was accented by green-trimmed windows with blue shutters. Dozens of mail order catalogs were perused, resulting in acquisition of heavy oak furniture, a completely furnished library, a huge kitchen with hot and cold water, wallpaper, and fine carpeting. Pre-dating Scotty’s Castle, this structure reportedly displayed none of the latter’s fine attributes, and was considered nothing more than a white elephant by its owner. The only way to forget such a structure is to blow it off the face of the earth, and that is precisely what Old John did one night with the aid of several boxes of dynamite.

Controversy Surrounding Lemoigne’s Death

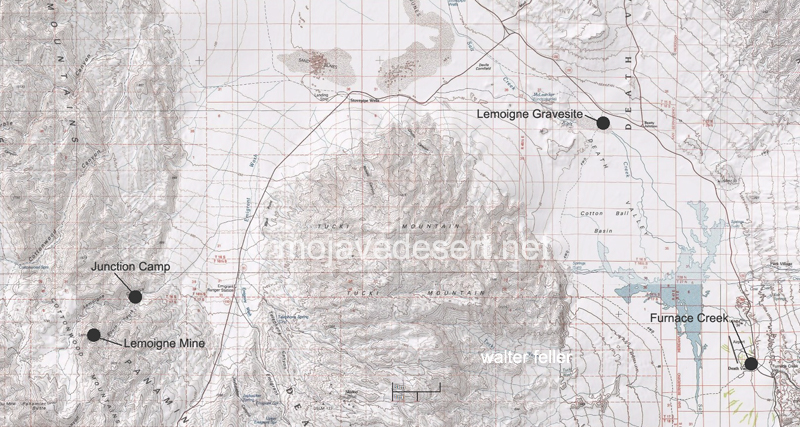

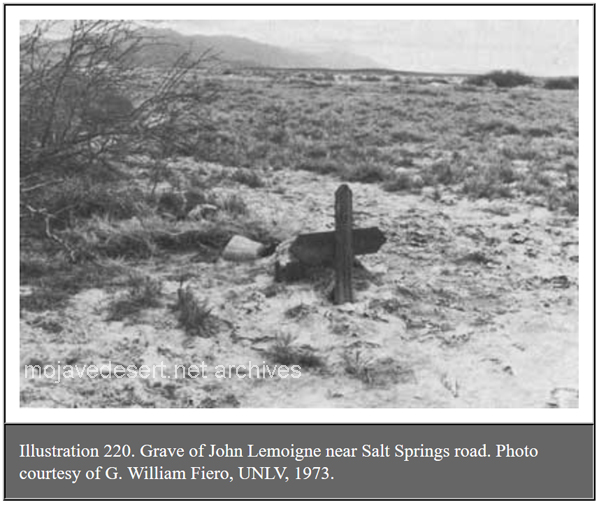

That incident, if true, was about the only undignified moment in Lemoigne’s life, which came to an end tragically in 1919. In death as in life Lemoigne has been the subject of considerable controversy. Many cannot even agree on the date of his demise, while, as Southworth writes, the number of people who claimed to have found and buried John Lemoigne reads like a Who’s Who of the desert region. Why Old John was heading toward Furnace Creek Ranch, or away from it, is not definitely known, although reportedly he had not been feeling well for some time and was journeying there to seek medical advice. Whatever the reason, he never reached his destination. According to Crampton he and Shorty Harris found the body lying under a mesquite bush about nine miles northwest of Furnace Creek Ranch near Salt Well. Apparently overcome by the heat or a sudden heart attack, Lemoigne had been unable to untie his burros, who perished with him. Proving his personal involvement in the event, Crampton says, are pictures he took of Old John and one of his burros as they lay when found. Reporting the incident at Furnace Creek Ranch, Crampton and Harris returned with Harry Gower, Oscar Denton, Tom Wilson, and a couple of other Indians for the burial, with Gower carving a grave marker.

According to Harry Gower, however, it was Death Valley Scotty who found Lemoigne eleven miles north of Furnace Creek and returned to the ranch to report it. Upon receiving the message at Ryan, Gower contacted the coroner at Independence and was told to go ahead and bury the body. Arriving at the scene with an Indian companion, Gower found the body partially eaten by coyotes and John’s gold watch hanging in a mesquite bush. Because of the hardness of the ground and the intense heat, the grave was only dug about two feet deep and was quite narrow. Lemoigne was wrapped in a blanket and lowered into the grave, over which a mound was erected and marked with stones and a board. Gower later sent the coroner the watch and a bill for $40 to cover costs of the burial detail. Gower states he was told later that Scotty felt he should have gotten the money, but no words ever passed between the two on the subject. Cower evidently did have some strong feelings about Crampton’s declared part in the whole affair:

The guy who is going to have a tough time getting squared with me is the alleged author who claims to have been associated with Le Moigne, and buried him on the desert. If he gains a bit of notoriety by his statement I have no objection as I got paid for my work. I’m sore because I doubt if he ever had the guts to dig a hole two feet deep in Death Valley in August.

Adding further confusion is Scotty‘s version:

In June 1918, I found him [Lemoigne] stretched out dead. He must have been on his way to Furnace Creek with his burros. I dug a hole and buried him right there by a clump of mesquite. Then I went on to Furnace Creek to give the notice. Cost me twenty dollars for feed for my string of mules. Gower got the ten-dollar fee for burying old John when the work was already done. I got nothing!

In 1922 when Sarah Perkins traveled through Death Valley, she by chance stumbled upon a sun-bleached board set in the sand. Written on it in pencil, she said, were the words “John Lemoign, Died Aug. 1919.” Nearby were the skeletons of two burros and a coffeepot beside a fireplace. This supports Gower’s contention that he buried John in August 1919, and pretty conclusively disputes Southworth’s romantic statement that “in deference to Old John, who always believed his burros were human, each body was buried in a separate grave.” At the time of his death John Lemoigne’s estate was valued at about $10.00 after all expenses were paid.

Later History of the Lemoigne Mine

Because no heirs were known to exist, Beveridge Hunter and Bill Corcoran relocated Lemoigne’s eight mining claims, soon, disposing of the property to a W.J. Loring and associates. Because of the area’s remote location, Hunter and Corcoran realized they would either have to sell the mine outright or enlist the cooperation of someone with the investment capital necessary to turn the property into a paying concern. A Brandon & Co. of Boston had an option on the group, but Brandon was killed before a sale could be consummated. Corcoran and Hunter then managed to interest Harry C. Stemler and Associates of Tonopah, who were in some way connected with the Loring interests, in the property, but they insisted on visiting the mine before making a firm decision. Despite a harrowing experience during the return from the mine, during which Stemler and Corcoran almost died from thirst and exhaustion, the former decided to take a bond on the property. The claims deeded to him in Lemoigne Canyon were the Blossom, Captain, Captain No. 2, Captain No. 3, Hunter, Atlantic, Pacific, and Sunshine.

In August, despite the heat, Corcoran was told to take charge of development work and intended despite the 132-degree temperature to begin a force immediately at three places on the ledge; ore would be hauled to Beatty by tractor across the floor of Death Valley. Incentive to begin operations was provided by an engineer for the Loring interests who declared that the ore in the mine would average 61-1/2% lead for the full length of the three claims, and who also estimated that there was $2,500,000 worth of ore in sight. Development work already consisted of a twenty-five-foot tunnel previously excavated by Hunter and Corcoran and a twenty-five-foot-deep shaft, plus several cuts made to keep track of the vein’s course and of the consistency of its values.

The eight claims acquired by Stimler were later quitclaimed to the Interstate Silver Lead Mines Corporation of Nevada, but by 1923 a W. R. McCrea of Reno and a John J. Reilly, who once leased on the Florence Mine at Goldfield, were developing the property, on which they held a lease with option to buy, and were driving a crosscut tunnel to intersect the rich ledge. In May 1924 it was thought that the main lode was discovered when a rich strike, “bigger than anything before encountered in any of the workings at the mine,” was made on the Birthday Claim west of the old workings.

By June Corcoran had purchased more machinery for the mine and, in addition, all the buildings and pipelines belonging to Carl Suksdorf at Emigrant Spring, with plans underway to make this one of the biggest lead-producing mines in the western United States. A year later John Reilly had organized the Buckhorn Humboldt Mining Company and had purchased the Lemoigne Mine from Corcoran and Hunter for a substantial amount of cash and stock. McCrea became the company’s manager and principal owner and, later, president, after Reilly’s death in March 1925. Immediate plans were made to construct an eight-mile auto truck route to the Trona-Beatty Road in order to facilitate shipping to the smelters. Four leasers were also working on ground near the company property, though by April the number had increased to ten, forcing two trucks to leave every day loaded with shipping ore. Property of the Lemoigne South Extension Mining Company (composed of Messrs. Turner, Burke, McDonald, Clark, and Smith) adjoined the Lemoigne Mine proper and was uncovering ore running up to 80% lead. [

Development was still being steadily pushed by the Buckhorn Humboldt people in the spring of 1926 to uncover a large amount of high-grade ore in sight as well as the vast quantities of low-grade milling ore that seemed to be present. Several lessees were at work, notably on the Miller Lease and the Dollar Bill Matthews ground. By May only four sets of leasers were operating, and the number was evidently reduced to three by June. In 1926 the California Journal of Mines and Geology described the mine as located in the LeMoigne District and still owned by the Buckhorn Humboldt Mining Company. It was under lease to L.P. (?) McCrea, M. L. Miller, and associates of Beatty, Nevada. A twenty-five-foot tunnel had been driven west in the canyon north of the main camp and was intersecting an ore lens from which 150 tons of ore had been shipped running 50% lead and three to five ounces of silver per ton. South of these workings on a ridge above Lemoigne Canyon a 165-foot tunnel had developed a lens from which 100 tons of ore had been shipped averaging 50% lead with five ounces of silver per ton. The ore was being hauled by truck to Beatty at a cost of $18 per ton. Two men were employed at the mine. The property must still have been active in 1928, because in May of that year Margaret Long mentions a road that was washed out and would have to be regraded by the next truck through to Lemoign.”

McCrae and the Buckhorn Humboldt Mining Company continued to hold the Lemoigne Mine from 1937 through 1948, although by 1938 the twelve claims were reported as idle. Bev Hunter later refiled on the property, subsequently leasing it to W. V. Skinner of Lone Pine, who produced a little ore in 1953. By 1962 Roy Hunter was evidently attempting some sporadic mining activity at the old mine. Total production from the property was said to have a gross value of approximately $38,000, realized from the shipment of over 600 tons of ore containing 30% lead, 7% zinc, and 4 ozs. of silver per ton. During its active lifetime up to 1963, the Lemoigne Mine was developed by about 600 feet of workings taking place on three levels and one sublevel, which were connected by a vertical shaft, and by three stopes. The shaft on the property had been extended to about eighty feet in depth. Again in 1974 mining activity resumed on the site, and by December 1975 a Harold Pischel was working on a previously unexplored hillside looking for sulfide ore. Material reportedly carrying 14 ozs. of silver per ton was being stockpiled at the adit entrance.

Present Status (1981)

The Lemoigne Mine is located in Lemoigne Canyon, the southernmost canyon of the Cottonwood Mountains, which form the northerly extension of the Panamint Range. The claims, ranging in elevation from 4,950 to 5,700 feet, are reached via a jeep trail, crossing an alluvial fan, that is often subject to severe washing and that trends north off of California State Highway 190 approximately three miles east of the Emigrant Ranger Station. The claim area is reached after about 9-1/2 miles of very rough 4-wheel driving. This writer was unable to personally view the mine because the road into Lemoigne Wash was barely visible following a series of heavy downpours in the area during the early fall of 1978. The site was visited by. the LCS crew in 1975 and the following account of structures found is based on their data and on that collected during an archeological reconnaissance of the area.

Near the junction of the North and South forks of Lemoigne Canyon are the remains of a campsite appearing to date from the 1930s. Only a leveled tent site and assorted debris were found. On up the road at the entrance to the Lemoigne claim the trail forks again into two short smaller canyons, both showing evidence of occupation by man. The southern or left one contains a relatively new corrugated-metal structure with a nearby pit toilet, a metal trailer, and the only structure of real historic significance in the area–the rock cabin built by John Lemoigne in the 1880s. This latter is a partial dugout, carved into the bedrock and lined with wooden cribbing. The front is part stone and part wood, with flattened five-gallon metal cans being used for paneling in some areas. Shelves are built into some of the walls, which tends to verify this as Old John’s home:

When Jean arrived in America, he had with him volumes of the classics in French, English, and German, which he kept on shelves in the stone cabin he built below his lead prospect in a canyon west of Emigrant wash . . . .

The cabin structure itself is intact but filled with garbage and debris. Crampton states that when he visited Lemoigne’s lead property around December 1919 the cabin had already been rifled of everything of value. Beyond these buildings the road leads to an active mine adit surrounded by some five other small adits dating from an earlier period.

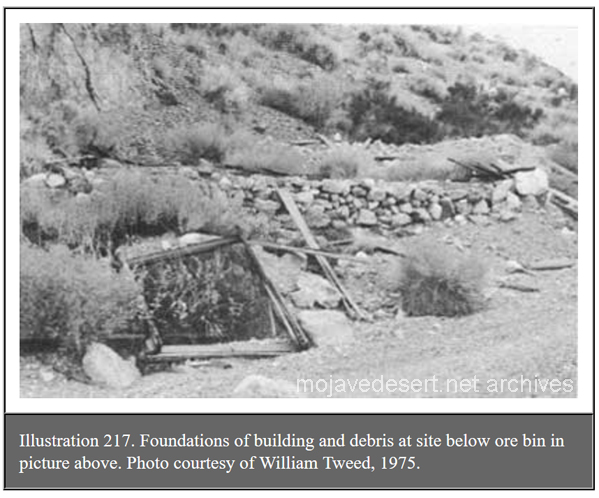

The northern canyon fork leads up past the site of at least four leveled habitation sites, about eight feet square, either for tent houses or wooden buildings, set against a cliff and about one-tenth of a mile below a one-chute ore bin. Wooden boards, stove parts, and old bedsprings were found scattered through the area. The ore bin is in a narrow box canyon and at the foot of a rail tramway descending on a very steep incline from a mine tunnel on the ridge above. The tramway was controlled by a gasoline-powered winch still in place at the entrance to the tunnel.

Evaluation and Recommendations

The Lemoigne silver-lead-zinc Mine was probably first worked in the late 1880s, though the exact location date was not found by this writer. The mine was only sporadically worked by Lemoigne, who spent most of his forty years in the Death Valley region searching for minerals and performing assessment work for fellow miners. A newspaper article in 1923, in fact, mentioned that Lemoigne had confined his development of the area to shallow surface holes. According to a recent study of the claims, they have been developed through the years by about 1,300 feet of workings. Most ore removed was high-grade, the many low- and medium-grade pockets being considered economically infeasible to mine during the 1920s when the mine saw its highest production rate. According to a 1976 report, the total value of all metals recovered at the Lemoigne Mine, based on January 1976 prices, would be about $116,000.

The historical significance of this site is not based on the volume of ore produced at the mine or on its monetary value. Its importance lies in its early discovery date and especially in its associations with John Lemoigne, considered by many to be the dean of Death Valley prospectors. It is not that Old John is completely forgotten–his lead mine is shown on the USGS Panamint Butte quad at the end of a canyon that also bears his name. His gravesite is marked on the Chloride Cliff quad just south of the Salt Springs jeep trail. (Attempts to locate the site by this writer were unsuccessful, though the wooden cross was still in place in February 1973.) It is simply that he is often overshadowed by the braggadocio of such highly-publicized wanderers of the desert as Death Valley Scotty and Shorty Harris. Leomoigne was a completely different breed, more attune in tastes and life-style to Pete Aguereberry, the other transplanted Frenchman in the valley who, like Old John, stayed to pursue a quiet and uneventful life in the desert they both loved so well.

Lemoigne’s biographer, Frank Crampton, expressed his appraisal of the man this way:

Old John typified the breed of prospectors and old-timers and the Desert Rats who centered on Death Valley. Few, if any, did any prospecting of any consequence in the valley, they were not looking for non-metallics but for gold, silver, lead, copper or one of the other of the lesser metals. Death Valley was not the place where metals were found in paying quantities and the breed knew it . . . . Old John was the best of them all. He had the knowledge of a highly educated man, and the fortitude to accept the fate that had befallen him when he arrived at Death Valley and learned that Daunet was dead. But the greatest of all attributes was that he loved the desert, and Death Valley best of all, and without effort adapted himself to it. Old John Lamoigne [sic] deserves imortality [sic] He was the epitome of them all and represents the best of a breed of men who are no longer.

Because the Lemoigne Mine was the scene of some of the earliest mining activity within the monument and the home of John Lemoigne until his death in 1919, the mine area and the stone cabin that Lemoigne built are considered to be locally significant and eligible for inclusion on the National Register. The leveled tent or house sites and ore bin in the box canyon probably date from the 1920s era of mining activity when the mine was being developed and was shipping ore. Some sort of camp had to have been situated here to house the Buckhorn Humboldt Mining Company employees and the various lessees. Based on the 1975 LCS research notes, these structures are not considered significant.

An interpretive marker near the stone cabin identifying the site would be appropriate. The tent foundations and old ore bin should be mentioned as probable vestiges of early twentieth-century activity in the area. An exhibit at the visitor center might dwell further on Lemoigne’s life, emphasizing his long tenure in the valley, his knowledge of the classics, and his degrees as a mining engineer–traits which set him apart from his desert comrades.

Attempts were made by this writer to determine the extent of mining enterprises in Cottonwood Canyon further north where Lemoigne had filed on some quartz claims in the late 1880s. An arduous all-day hiking trip failed to turn up any signs of such activity. A monument employee, however, stated that about 1976 the remains of two buildings were found at Cottonwood Springs. One corrugated steel and tin shack contained a wood-burning stove and a set of bedsprings. No evidence of mining was seen in the immediate area, and no prospect sites are shown on the USGS Marble Canyon quad.

from: Death Valley Historic Resource Study

A History of Mining – Vol. I, Linda W. Greene – March 1981