He Witnessed the Death Valley Tragedy of ’49

By J.C. Boyles – Desert Magazine — Feb – 1940

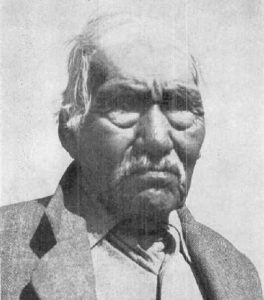

When the ill-fated Jayhawker and Bennett-Manly parties trekked across Death Valley in 1849 the white gold-seekers were in mortal fear of the Indians who lurked along the trail. Today, 90 years later, Indian George Hansen, venerable patriarch of the Death Valley Shoshones who as a boy witnessed the tragedy of the Americans, discloses that the Indians also were afraid of the whites. “The hearts of our people were heavy for these strange people,” he said, “but we were afraid. They had things that made fire with a loud noise and we had never seen these before.” Indian George is nearly 100 years old today, but he has a vivid recollection of the incidents of his long life on the Death Valley desert. The accompanying interview was given to a man who has for many years been an intimate friend and advisor to the aged Indian.

Many wheels spin through the Panamint range these days, rolling along to Death Valley with well-dressed and well-fed sightseers bound for de luxe winter resorts which draw visitors from all over the world. The sleek automobiles and their big rubber tires attract only a casual glance now from Indian George. But he remembers when he and his people of the Shoshone tribe nearly 90 years ago saw for the first time a wheel in Death Valley. The wheels were creaking, iron-rimmed wagonwheels of the ill-fated ragged Jayhawker party on their tragic way to California. It was around Christmas time in 1849. Indian George was a small boy then. He was born at Surveyor Well in Death Valley about the year 1841. And the first white man he saw on the desert so long ago in a world he had known as inhabited exclusively by Indians terrified him. He ran from the sight and thus won his tribal name, Bah-vanda-sava-nu-kee (Boy-Who-Runs-Away).

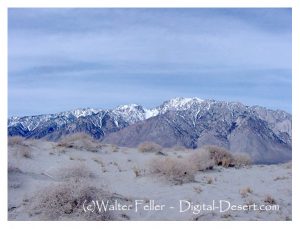

“Boy-Who-Runs-Away” is a venerable patriarch of his people now. Nearing his 100th birthday, he has the dignity of great age. His head is as white as the winter snow on Telescope peak high above his home in Panamint valley. Despite the burden of his years, he retains a delightful sense of humor that makes him chuckle at recollection of the incident that gave him his name. And his memory goes back clearly to the days before the white man invaded his world.

On a late October day we sat in the shade of the cottonwoods at the old Indian ranch where he has made his home for the past 70 years. There he lives with his daughter Isabel, granddaughter Molly and Old Woman, his sister-in-law. At nearby Darwin he has many great-grandchildren.

Bah-vanda-sava-nu-kee’s home place is watered by a stream from the melting snows of the Panamints. The pungent smell of goats permeated the air.

Leaves of the cottonwoods had begun to turn yellow with the first cold of autumn, dust devils swirled over the mud flats, a blue haze lay over the mountains. Lean hungry mongrel dogs sniffed at my feet, Old Woman silently shelled pinon nuts, the silence broken only by the cracking of hulls.

Around us was the region called home by a small band of Shoshones for many generations before the white man’s coming. Coville called the tribe the Panamint Indians, most southerly of the Shoshonean family whose homes were on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada and northward nearly to Canada. In Death Valley and along its border the desert band lived widely separated, in wickiups close to springs or water holes, utilizing in a barren, forbidding territory, every edible shrub and root, every living thing that walked and crawled.

The women gathered mesquite beans, wild grass seed and pinon nuts which were winnowed and ground into coarse flour. The men snared rabbits and quail and hunted the wily bighorn sheep in the nearby mountains.

Bah-vanda-sava-nu-kee has seen here in his lifetime a development of human history equivalent to man’s progress through all that long, long stretch of time since the first wheel astonished travelers afoot. During the past 20 years I have studied the story of his life.

While Old Woman shelled the pinons,

I said:

“Grandfather, you have seen many winters and the wisdom of an old man is good. That is why I have come to you to hear of the old times.”

After a long silence, Bah-vanda-savanu-kee spoke:

“My son, you are Kwe-Yah, the Eagle.’ I have known your father for many, many years. You have been to the white man’s school and have learned his ways, many of which are good, and you

understand our people and many of our ways are good.

“I am growing old, my limbs creak, my eyes are dim with age. To you, my son, I can talk plain and you will understand without me saying foolish things like when I talk to white people.”

There was another interval of silence, and then he continued, speaking slowly and deliberately. As nearly as I can do so, I use his own words:

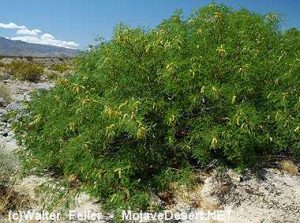

Long ago I was born in a camp of mesquite in To-me-sha, they call that place Death Valley. It was at Surveyor Well. From the earliest time I can remember we would move away in the summer to the high cool country among the juniper and pinon trees. There we would stay until the pinon nut harvest was over, returning to the valley when the snow came.

When there was plenty of meat every one was happy, even E-shev-ipe the coyote and Wo-te-ah the fox smelled the meat cooking over the hot stones and came for their share. When every one had eaten all he could hold, there was story telling and dances. Sometimes we played the hand game and sang the gamblers song all night long. Those were happy days with our people.

Cold winter evenings we sat about the camp fire, in the shelter of the mesquite, the old men told stories of days that were gone. Our women worked at basketmaking, some baskets were made for gathering seeds and pinon nuts, others were for beauty. It was a gift of our women to make good baskets.

Old Kaw “the crow” was the best story teller, he told the stories over and over, so that the boys would know and remember, and he went away back the life time of many old men. He told of the Mojaves and how our young men drove them from the valley. They came in from the south to steal our pinon-nut caches and carry off our women. We did not like these people, we were high above them. Always after a fight they built a big fire and burned their dead ones. Long after this when I was a young man, that is, after the white man came, the Mojaves came back and killed white men and made much trouble. This time we helped the white men who were good to us. White men gave us guns and went with us on the war path. We found the Mojaves near that place Mojave where the railroad is now and killed many and brought back the white man’s stock. After that we never saw the Mojaves again. They were not our kind of people.

My father Inyo (Place-of-the-Spirit) was head man at that time, what the white man calls a chief. When our people had trouble they came to him, and he he listened, and what he said to them was right. In my father’s time I heard of the animal the white man calls buffalo but we never saw that animal. We traded willow baskets, salt and arrow heads for the buffalo hide from other Indians who came down from the north. Our people used this hide for moccasins and made warm blankets from rabbit skins cut in strips and twisted them sewed together. This way the hair was on both sides and very warm in winter time.

When I was a little boy I wandered over the desert far from home, always looking for something to eat. I learned how to snare rabbits and quail and hunt Cuc-wata the chuckawalla. Cuc-wata was quick, he would run and hide in the crack of big stones and blow himself full of wind, so he could not be pulled out. For this hunting I carried a sharp stick, I catch hold of his tail and punch a hole to leave out the wind, then I could easy pull him out. This meat was very good.

When I found the track of To-koo-vichite the wild cat, I would trail him to his den, and later tell my father who would smoke him out and kill. This meat was very sweet.

Sometimes when I would start out to hunt, Woo-nada-gum-bechie (Dust Devil) would cross my path, then I would always return, for that was a bad sign. The old men say that is the ghost of one who died and maybe that is so.

When Oot-sup-poot, the meadow lark, came back that was a good sign that cold wind had gone. Then I could travel far with my bow and arrow and some times bring home big birds that were going north. I was becoming a big hunter and brought much meat to my mother’s wickiup. I learned to track and use the bow and arrow when very young. My father made the arrows from a hollow reed that grows in the canyons. You can find that kind of reed over there in the canyon where this water comes from. We placed a sharp stick about as long as a hand in the end, this stick we burned in a fire and scraped with a stone to a hard sharp point. Some arrows we pointed with black stone (obsidian) that came from the Coso hills. That time there was many Wa-soo-pi (big horn sheep) on Sheep mountain and all over the Ky-eguta (Panamint range). No Indian boy today could hunt them like we did with bow and arrow. Some time I trailed Wasoo-pi for three, four days. When I see him lay down, I crawl close slow, slow, like a fox, from rock to rock, always with the wind in my fact;, when he would raise his head to smell the wind, I lay flat without a move. When I get close, I raise up slow, slow, and drive the arrow into meat.

When I was about as high as that wagon wheel, (pointing to an old wheel leaning against the corral fence) may be about ten or 12 summers, a big thing happened in my life.

This I must remember well, and in the telling, tell it straight. Snow was on See-umba mountain (Telescope peak) when this happened.

A strange tribe of other people (the Jayhawker-Manly- Bennett Party 1849) came down Furnace Creek, some walking, slow like sick people and some in big wagons, pulled by cows. They stopped there by water and rested. When other Indians see them, they run away and tell all other Indians at other camps.

Our people were afraid of this strange people. They were not our kind and these cows my people had never seen before.

Our people were afraid of this strange people. They were not our kind and these cows my people had never seen before.

Never had they seen wagons or wheels or any of the things these people had, the cows were spotted and bigger than the biggest mountain sheep, with long tails and big horns. They moved slow and cried in a long voice like they were sick for grass and water.

Some of these people moved down the valley, some moved up, and they stopped at Salt creek crossing. Them that moved down the valley stopped where Indian Tom Wilson has ranch at Bennett’s well.

When it came night, we crawled close, slow like when trailing sheep. We saw many men around a big fire. They killed cows and burned the wagons and made a big council talk in loud voices like squaws when mad. Some fall down sick when they eat the skinny cows. By and by they went away, up that way where Stove Pipe hotel is now, they walk very slow, strung out like sheep, some men help other men that are sick. One man, he can go no more, he lay down by a big rock, that night he went to his fathers. As they go, they drop things all along the trail, maybe they are worthless things, or too heavy to carry.

After they go we went to that place at Salt creek and found many things that they left there. Because some died, we did not touch those things. When they burned the wagons some parts did not burn, that was iron, and we did not understand this.

Those people who went down the valley to Bennett’s Well stayed there a long time. They had women and children. By and by they went away, all go over Panamints and we never see them again. The hearts of our people were heavy for these strange people, but we were afraid, they had things that made fire with a loud noise and we had never seen these before.

After this happened we were afraid more of the strange ones would come. We watched Furnace creek for a long time, but no more come.

May be about three or four summers after this, I was on the trail with my father in Emigrant canyon, when we see man tracks that was not made with moccasins, my father, he say: “Look, not made by Shoshone.”

We followed these tracks and when we come around by big rock we saw a white man there, very close. When we see him we stop quick, I run. away, may be that is why they call me “Boy-Who-Runs-Away.”

This white man made peace sign to my father and give him a shirt, when I see that, I come back. That place was near Emigrant spring.

I think that white man was scared as much as we were. He talked in a strange tongue and made signs with his hands. He was not white, he was same color as a saddle and because of this color I thought he looked like a sick Indian, he had long hair on his face, not like our people.

After this meeting from time to time other white men come into our country. They were rock-breakers looking for the yellow-iron. Mostly they come in pairs without their women, this we thought was strange for it is not a custom of our people to go that way. There were strange stories coming to us of many white people, in the valley of the river (Owens valley) by the high mountains west of here that made war on our people and killed many. Hearing this we were afraid there would be trouble.

After this meeting from time to time other white men come into our country. They were rock-breakers looking for the yellow-iron. Mostly they come in pairs without their women, this we thought was strange for it is not a custom of our people to go that way. There were strange stories coming to us of many white people, in the valley of the river (Owens valley) by the high mountains west of here that made war on our people and killed many. Hearing this we were afraid there would be trouble.

(The old man shifted his seat to throw a stick at a yelping dog)

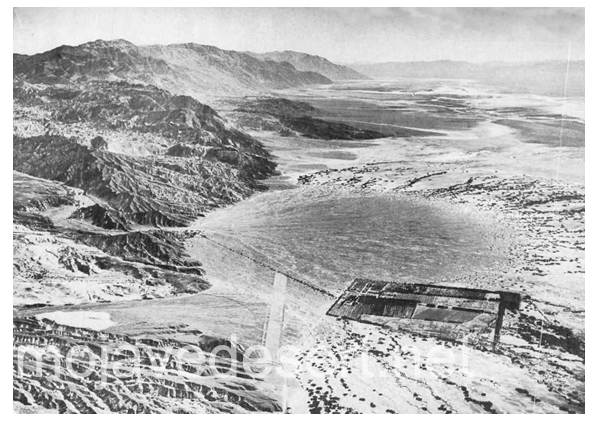

By this time I was married and living not far from Wild Rose spring, and again a big thing happened in my life. This time many white men with Mexicans and Chinese came to the Panamints and all go up that way in what the white man calls Surprise canyon. They built many houses and they all stop there.

I did not know there were so many people and so many different kinds, they brought horses, mules, burros and cows. They called that place Panamint City.

They made roads all over the desert to that place where they all lived. You can see the road now in Surprise canyon, that was a long time ago. I think most of those people have gone to their fathers.

These white men all carried guns and some times they fight among themselves.

At the time I worked with Hungry Bill, my brother-in-law, for a Mexican packer, cutting and packing pinon timber for the mines. He had many burros, these were the first we ever saw. (The old man laughed to himself). It was not long before we had burros of our own. Hungry Bill was good at finding things that were lost and I think some of those burros were not “lost.”

Learns Mule Skinner’s Language

First I learned to speak a little Mexican, it was easier to learn, then I learned a little American, at first only the words the mule skinners called the mules when they were mad.

Later I learned to prospect and find the metal those white people wanted so badly. I did very good but never received anything but grub and promises from those people. One man he gave me a check, when I showed it to another white man he laughed. May be that was a

white man’s joke. One white man I packed for, his name was George. We prospect all over the Ky-e-gutas. When we go out I tell him, “You stay back of me, this is my country,” when we comeback to Panamint City where they all live, I tell him, “Now, you go first, this is your country.”

Lots of white men have fun, they say, “Hello George, he your son?” After that every one called me George, that’s how I got that name.

Another man who was a “government man” gave me that name “Hansen,” he said I must have a name for the books, at Washington so Uncle Sam would know me. (The old man laughed). I

don’t know this Uncle Sam, but I guess he is all right, for when my son Mike or daughter Isabel is sick he sends a medicine man from the agency.

Too Many Beans for Bill

“Hungry Bill” he got his name from the white people at Panamint City. He was always hungry like a coyote, and a pretty bad Indian. I guess the government man did not give him another name because he was not much good, may be Uncle Sam didn’t want him on the books.

One white man at Stone Corral put some medicine in beans. When Hungry Bill eat all he could hold, he got sick. After that he never liked beans any more. About that: time they made another place at Kow-wah and called that place Ballarat. When they come in from outside

they stop there on way to Panamint City. Pretty soon some horse soldiers come and stopped at that place, the chief of those soldiers had a Ka-naka (Negro) who worked for him. When I first saw that black man I thought he was a white man burned black.

Hungry Bill, he was smart Indian. One time he made camp by the road, two white men come along, they have guns, when they see Hungry Bill they shoot at ground, they say “Dance, Injun,

dance.” Hungry Bill he did that, he dance close by sage brush by his gun, when white men make a big laugh, quick, Hungry Bill he pick up his gun, point at white men, he say “Now you dance same me.” This time Hungry Bill had a big joke on white men.

After all those people go away from Panamint City they leave many things, that is where I got many things you see about this ranch. One man he brought those stage wagons and he say: “George, I leave them here with you, some day I come back and get them.” He never came back, that was a long time ago.

Long time after they all go away, more white men come, this time to Sheep mountain. They call that place Skidoo. Me and my cousin Shoshone Johnnie we packed wood and timber to that place. After they have a big fight, Joe Simpson he shoot Jim Arnold, other white men

hang Joe Simpson by his neck, after that we stayed away. One white man he give to my daughter Isabel a picture of Simpson hanging by his neck. That was not good, maybe Simpson was drunk when he shot Arnold. It’s bad way to die, man’s spirit cannot get out when he dies with rope around the neck.

In this telling I must not: forget my friend John Searles.

Across the mountains to the south of here there is a dry white lake, where in the old days our people went for salt. There is a town there now and a big mill. They call that place Trona. I go

there often, and have many friends at that place. When I go there for grub, every one say “Hello George, how are you?” With my father and Hungry Bill we went there for salt long ago, that is where I met this man. He had a camp and horse corral by the lake. When we saw this, we stayed away. That night Searles he came to our camp and made signs for work.

My father and I worked there a long time, we liked the Chinamen, they were little bit like our people. Some white man told to me “Chinaman and Injun all same.” May be so, but I do not believe that.

When we went away, Searles he said: “George, you are always welcome and any time you stop here, China boy will feed you, but not Hungry Bill, you tell him to stay away.”

“Take Mule Home, Eat ’em”

Then he say: “Come here,” and he showed me old mule in the corral, he said: “You taken home, make jerky, plenty good meat. You no keep him, you eat, sabe?” We did this, for in the old days any kind of mea: was good. John Searles was a good man and known to our people as “Bear Fighter.” When he was a young man he had a big fight with a bear in Tehachapi mountains, that is how he got that name:. He had big scar on neck from that fight, when he talk to me he hold his head this way (the old man bent his head slightly to the left shoulder).

Many times after that I thought of John Searles and the good meat we eat at his

camp. Some people say he killed Indians, but that is not true.

That time Hungry Bill would go away for a long time south of Mojave, when he come back, he always bring horses and mules, then all the Indians would have plenty meat. This was not good and caused lots of trouble- with the white men. I think that is why Searles told him to stay away.

The lean dogs sniffed the air and ran off barking. It was Molly, granddaughter of Bah-vanda-sava-nu-kee bringing in the goat herd to the shelter of the corral for the night.

Old Woman threw a stick on the dying fire, the flames lit up the old Indian’s face, “My son, the few thing I have told you are but the flutter of a crow’s wing in my life. Soon I will go to the land of my fathers along with all these other people I have told you about.’

-end-