from: Loafing Along Death Valley Trails

A Personal Narrative of People and Places by William Caruthers

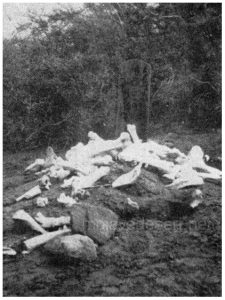

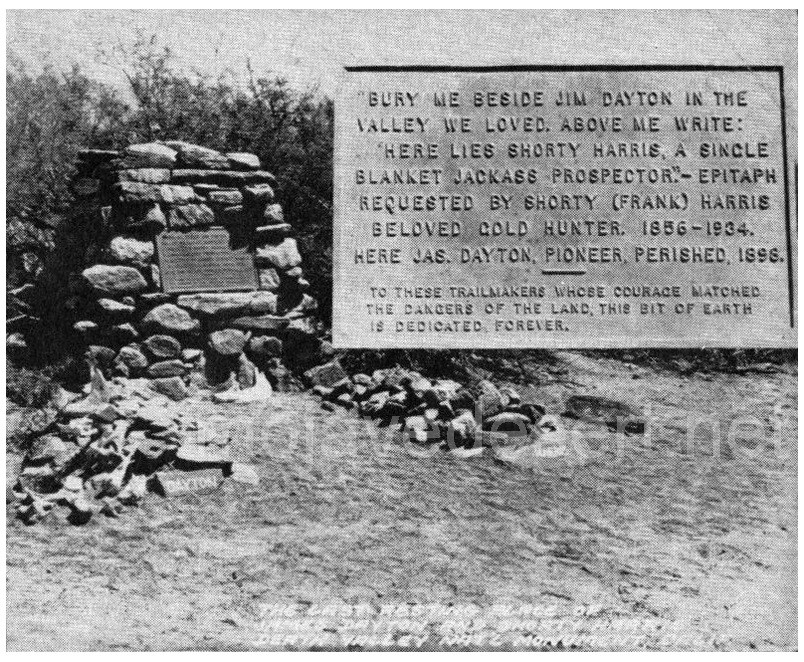

For years, on the edge of the road near Tule Hole, a rough slab marked Jim Dayton’s grave, on which were piled the bleached bones of Dayton’s horses. On the board were these words: “Jas. Dayton. Died 1898.”

The accuracy of the date of Dayton’s death as given on the bronze plaque on the monument and on the marker which it replaced, has been challenged. The author of this book wrote the epitaph for the monument and the date on it is the date which was on the original marker—an old ironing board that had belonged to Pauline Gower. In a snapshot made by the writer, the date 1898, burned into the board with a redhot poker shows clearly.

The two men who know most about the matter, Wash Cahill and Frank Hilton, whom he sent to find Dayton or his body, both declared the date on the marker correct.

The late Ed Stiles brought Dayton into Death Valley. Stiles was working for Jim McLaughlin (Stiles called him McGlothlin), who operated a freighting service with headquarters at Bishop. McLaughlin ordered Stiles to take a 12 mule team and report to the Eagle Borax Works in Death Valley. “I can’t give you any directions. You’ll just have to find the place.” Stiles had never been in Death Valley nor could he find anyone who had. It was like telling a man to start across the ocean and find a ship named Sally.

At Bishop Creek in Owens Valley Stiles decided he needed a helper. There he found but one person willing to go—a youngster barely out of his teens—Jim Dayton.

Dayton remained in Death Valley and somewhat late in life, on one of his trips out, romance entered. After painting an intriguing picture of the lotus life a girl would find at Furnace Creek, he asked the lady to share it with him. She promptly accepted.

A few months later, the bride suggested that a trip out would make her love the lotus life even more and so in the summer of 1898 she tearfully departed. Soon she wrote Jim in effect that it hadn’t turned out as she had hoped. Instead, she had become reconciled to shade trees, green lawns, neighbors, and places to go and if he wanted to live with her again he would just have to abandon the Death Valley paradise.

Dayton loaded his wagon with all his possessions, called his dog and started for Daggett.

Wash Cahill, who was to become vice-president of the borax company, was then working at its Daggett office. Cahill received from Dayton a letter which he saw from the date inside and the postmark on the envelope, had been held somewhere for at least two weeks before it was mailed.

The letter contained Dayton’s resignation and explained why Dayton was leaving. He had left a reliable man in temporary charge and was bringing his household goods; also two horses which had been borrowed at Daggett.

Knowing that Dayton should have arrived in Daggett at least a week before the actual arrival of the letter, Cahill was alarmed and dispatched Frank Hilton, a teamster and handy man, and Dolph Lavares to see what had happened.

On the roadside at Tule Hole they found Dayton’s body, his dog patiently guarding it. Apparently Dayton had become ill, stopped to rest. “Maybe the sun beat him down. Maybe his ticker jammed,” said Shorty Harris, “but the horses were fouled in the harness and were standing up dead.”

There could be no flowers for Jim Dayton nor peal of organ. So they went to his wagon, loosened the shovel lashed to the coupling pole. They dug a hole beside the road, rolled Jim Dayton’s body into it.

The widow later settled in a comfortable house in town with neighbors close at hand. There she was trapped by fire. While the flames were consuming the building a man ran up. Someone said, “She’s in that upper room.” The brave and daring fellow tore his way through the crowd, leaped through the window into a room red with flames and dragged her out, her clothing still afire. He laid her down, beat out the flames, but she succumbed.

A multitude applauded the hero. A little later over in Nevada another multitude lynched him. Between heroism and depravity—what?

Although Tule Hole has long been a landmark of Death Valley, few know its story and this I believe to be its first publication.

One day while resting his team, Stiles noticed a patch of tules growing a short distance off the road and taking a shovel he walked over, started digging a hole on what he thought was a million to one chance of finding water, and thus reduce the load that had to be hauled for use between springs. “I hadn’t dug a foot,” he told me “before I struck water. I dug a ditch to let it run off and after it cleared I drank some, found it good and enlarged the hole.”

He went on to Daggett with his load. Repairs to his wagon train required a week and by the time he returned five weeks had elapsed. “I stopped the team opposite the tules, got out and started over to look at the hole I’d dug. When I got within a few yards three or four naked squaw hags scurried into the brush. I stopped and looked away toward the mountains to give ’em a chance to hide. Then I noticed two Indian bucks, each leading a riderless horse, headed for the Panamints. Then I knew what had happened.”

Ed Stiles was a desert man and knew his Indians. Somewhere up in a Panamint canyon the chief had called a powwow and when it was over the head men had gone from one wickiup to another and looked over all the toothless old crones who no longer were able to serve, yet consumed and were in the way. Then they had brought the horses and with two strong bucks to guard them, they had ridden down the canyon and out across the desert to the water hole. There the crones had slid to the ground. The bucks had dropped a sack of piñon nuts. Of course, the toothless hags could not crunch the nuts and even if they could, the nuts would not last long. Then they would have to crawl off into the scrawny brush and grabble for herbs or slap at grasshoppers, but these are quicker than palsied hands and in a little while the sun would beat them down.

The rest was up to God.

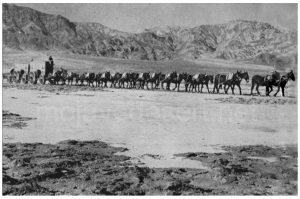

The distinction of driving the first 20 mule team has always been a matter of controversy. Over a nation-wide hook-up, the National Broadcasting Co. once presented a playlet based upon these conflicting claims. A few days afterward, at the annual Death Valley picnic held at Wilmington, John Delameter, a speaker, announced that he’d made considerable research and was prepared to name the person actually entitled to that honor. The crowd, including three claimants of the title, moved closer, their ears cupped in eager attention as Delameter began to speak. One of the claimants nudged my arm with a confident smile, whispered, “Now you’ll know….” A few feet away his rivals, their pale eyes fixed on the speaker, hunched forward to miss no word.

Mr. Delameter said: “There were several wagons of 16 mules and who drove the first of these, I do not know, but I do know who drove the first 20 mule team.”

Covertly and with gleams of triumph, the claimants eyed each other as Delameter paused to turn a page of his manuscript. Then with a loud voice he said: “I drove it myself!”

May God have mercy on his soul.

A few days later I rang the doorbell at the ranch house of Ed Stiles, almost surrounded by the city of San Bernardino. As no one answered, I walked to the rear, and across a field of green alfalfa saw a man pitching hay in a temperature of 120 degrees. It was Stiles who in 1876 was teaming in Bodie—toughest of the gold towns.

I sat down in the shade of his hay. He stood in the sun. I said, “Mr. Stiles, do you know who drove the first 20 mule team in Death Valley?”

He gave me a kind of et-tu, Brute look and smiled.

“In the fall of 1882 I was driving a 12 mule team from the Eagle Borax Works to Daggett. I met a man on a buckboard who asked if the team was for sale. I told him to write Mr. McLaughlin. It took 15 days to make the round trip and when I got back I met the same man. He showed me a bill of sale for the team and hired me to drive it. He had an eight mule team and a new red wagon, driven by a fellow named Webster. The man in the buckboard was Borax Smith.

“Al Maynard, foreman for Smith and Coleman, was at work grubbing out mesquite to plant alfalfa on what is now Furnace Creek Ranch. Maynard told me to take the tongue out of the new wagon and put a trailer tongue in it. ‘In the morning,’ he said, ‘hitch it to your wagon. Put a water wagon behind your trailer, hook up those eight mules with your team and go to Daggett.’

“That was the first time that a 20 mule team was driven out of Death Valley. Webster was supposed to swamp for me. But when he saw his new red wagon and mules hitched up with my outfit, he walked into the office and quit his job.”

~ the end ~