The following is an excerpt from ‘White Heart of Mojave’ by Edna Brush Perkins

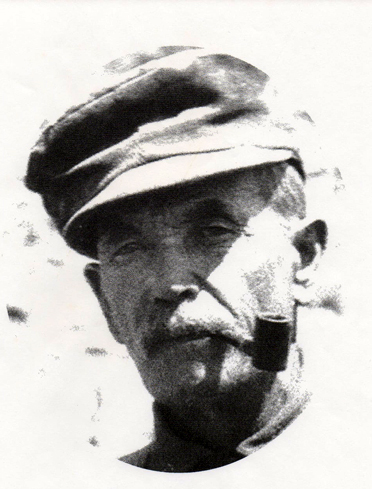

It was discouraging, but we persevered until we found a real old-timer. He was known as Shady Myrick. We never discovered his Christian name though he was a famous desert character. Wherever we went afterward everyone knew Shady. Evidently, the name was not descriptive for all agreed on his honesty and goodness. He was an old man, rather deaf, with clear, very straightforward-gazing eyes.

Most of his life had been spent on the Mojave as a prospector and miner, and much of it in Death Valley itself. The desert held him for her own as she does all old-timers. He was under the “terrible fascination.” As soon as we explained that we had come for no other purpose than to visit his beloved land he was eagerly interested and described the wonders of Death Valley, its beautiful high mountains, its shining white floor, its hot brightness, its stillness, and the flowers that sometimes deck it in the spring.

“If you go there,” he said, “you will see something that you’ll never see anywhere else in the world.”

He had gem mines in the Panamints and was in the habit of going off with his mule-team for months at a time. He even said that he would take us to the valley himself were he a younger man. We assured him that we would go with him gladly. We urged him—you had only to look into his eyes to trust him—promising to do all the work if he would furnish the wagon and be the guide, innocently unaware of the absurdity of such a proposal in the burning heat of Death Valley; but he only smiled gently, and said that

he was too old.

Silver Lake turned out to be the place for us to go after all. He described how we could

drive straight on from Joburg, a hundred and sixteen miles. There was a sort of a road all the way. He drew a map on the sand and said that we could not possibly miss it for a truck had come over six weeks before and we could follow its tracks.

“It ain’t blowed much, or rained since,” he remarked.

“But suppose we should get lost, what would we do?”

“Why should you get lost? Anyway, you could turn around and come back.”

We looked at each other doubtfully. In the far-spreading silence around Joburg the idea of getting lost was more dreadful than it had been at Barstow. There was not even a ranch in the whole hundred and sixteen miles. We hesitated.

“You are well and strong, ain’t you?” he asked. “You can take care of yourselves as well

as anybody. Why can’t you go?”

“You have lived in this country so long, Mr. Myrick,” I tried to explain, “you do not understand how strange it is to a newcomer. How would we recognize those mountains you speak of when we do not even know how the desert mountains look? How could we find the spring where you say we might camp when we have never seen one like it?”

“You can do it,” he insisted, “that’s how you learn.”

“And there is the silence, Mr. Myrick,” I went on, hating to have him scorn us for cowards,” and the big emptiness.”

He understood that and his face grew kind.

“You get used to it,” he said gently.

It was refreshing to meet a man who looked into your feminine eyes and said: “You can do it.” It made us feel that we had to do it. We spent a whole day on a hilltop near Joburg looking longingly over the sinister, beautiful mountains and trying to get up our courage. Happily we were spared the decision. Two young miners at Atolia sent word that they were going over to Silver Lake in a few days and would be glad to have us follow them. Perhaps it was Shady’s doing. We accepted the invitation with gratitude.

He understood that and his face grew kind.

“You get used to it,” he said gently. . . .

Chap. II – How We Found Mojave