Piute Hill Fort Best Preserved Mojave Outpost

By L. BURR BELDEN

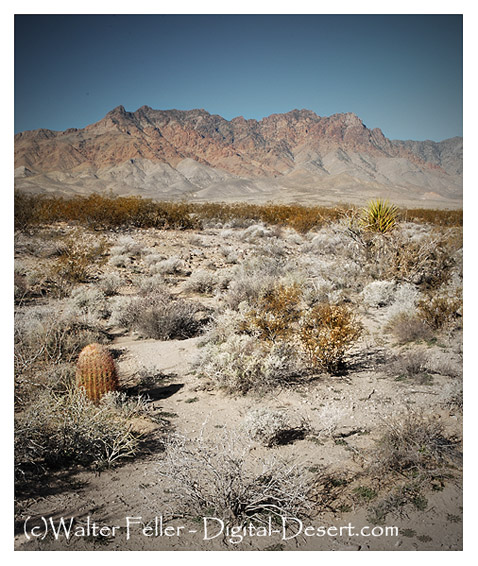

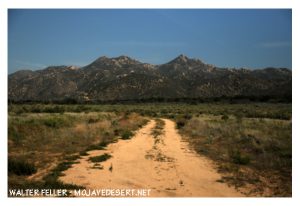

Fortifications along the western extension of the Santa Fe trail, route of the Whipple survey, were built initially because of Indian attacks on covered wagon trains of settlers. The Mojave War followed the massacre of one train by Indians at the Colorado River crossing a few miles above the present Needles.

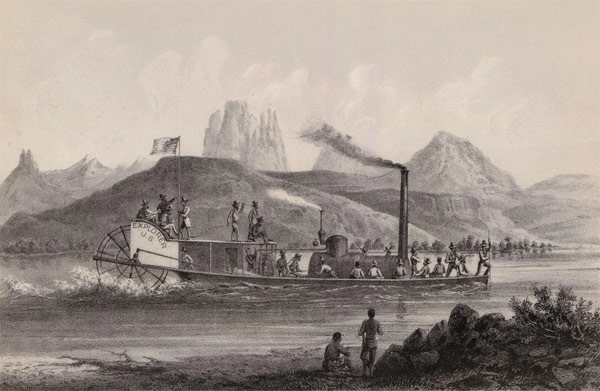

The Army was not slow in punishing the Mojave tribes, and entire regiment being collected at Fort Yuma and going upstream. This was in the winter of 1858-59. The initial fort, Ft. Mojave, was established at the time. Supplying of this river outpost was both expensive and difficult.

Soldiers attacked

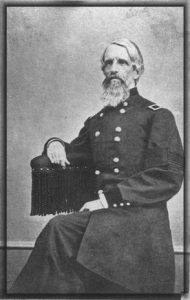

The road over the desert San Bernardino had been given a bad name by Lt. Col. William Hoffman would take in the company of mounted infantry in a small dragoon escort from the Cajon Pass to the river. Hoffman’s command had been attacked by Indians in route. The Col. was under orders to find a site for a desert fort. He saw nothing between Summit Valley in the river he considered a likely site. In fact, Hoffman condemned the entire route as unsuited for travel.

It is probable the Hoffman report influenced the Army in initially supplying Fort Mojave by steamer from Yuma. When the river was slow and supplies could not be taken at far upstream the fort garrison was desperate. At this juncture In Winfred Scott Hancock, the same officer who appeared in a recent issue of the series, called on the Banning stage and freight lines to take supplies through. Banning’s experience Teamsters had no trouble They drove again heavy freight wagons, each drawn by eight mule teams to the river in 16 days. The Fort Mojave garrison again had both food and ammunition.

Cady Old Site

Hancock at the time an assistant quartermaster, prove that not only the Mojave Valley road was practical. He also reduce the Army’s transport expense to Fort Mojave by two thirds. The hall from drum barracks at Wilmington to the Colorado River via Cajon Pass cost only a third as much per pound as the long water haul around Baja California and transfer shipment to river steamer.

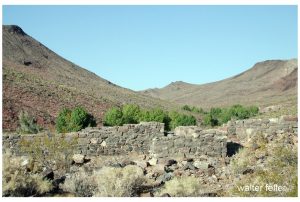

The site of Camp Cady was used as an Indian “fort” even before California became a part of the United States. Indians engaged in stealing horses from the Mexican ranchos built a crude sort of stronghold on the rocky hillsides of the Mojave River near that spot. It was a few miles East of the old Spanish Trail and also guarded the entrance to narrow Afton Canyon which could serve as an escape route if pursuit became too hot.

There is documentary evidence of the Indian use of their crude stronghold in 1845 point Benjamin Wilson, the Don Benito of Mexican rule, meeting Indians there in battle in 1845 a few days after the historic discovery of Bear Valley.

Wilson’s account of the pursuit of the horse thieves attributed depredations to renegade Indians from Mission San Gabriel but it is probable Sun desert tribes had Braves in the raiding parties. Wilson was alcalde at Jurupa and was called upon by Gov. Pico to punish the Indians. The acalde gathered a large posse including 22 young Californians mounted on fleet horses. The larger party in fact train went up Cajon Pass. Wilson in the young ranchers took the route up to Santa Ana Canyon, enjoyed hunting bear in what Wilson named Bear Valley, and joined the pack train somewhere near Rancho Verde in the present Apple Valley.

Wilson, wounded by a poisoned arrow, had his life saved by Lorenzo Trujillo. Trujillo, a New Mexican, was leader in the little colony of Agua Mansa and its twin town, Trujillo. In the Apple Valley fight the Indians were defeated in three of them killed. Wilson shot the notorious Joaquin, the ex-mission Indian, who was a ringleader among the horse thieves.

Several of Wilson’s Horseman pursued the remnant of the Indians down the Mojave though the wounded Wilson was forced to turn back. Nothing Indians halted in their crude fort near the site of Camp Cady. There, though the entrenched behind rocks, they were again defeated and dispersed.

In addition to the soldiers at the Mojave Desert forts there were a few civilians quartered at some of the posts. For instance, the returns of Camp Cady for December 1866 indicate an assistant wagon master was stationed there. He was paid $75 a month. Teamsters, their number not specified, received hundred and $75 a month, and herders $35 a month. Other notations would indicate the herders, at least some of them, were Indians. The Teamsters, whose work was the most skilled, where the aristocrats of the road whether they drove Concord stages and six horses or whipped along multiple freight teams. The Army officers themselves received far less pay.

There were also, at least at Cady and Mojave, sutler stores. The Army had no canteen or post exchange in that. And contractors, called settlers, were granted the privilege of establishing stores on military reservations and also, for that matter, with armies in the field. Suites that supplemented the monotonous menu, tobacco and whiskey as well as such notions as red, writing paper and ink were for sale at the sutler stores.

Soldiers receiving $7.50 a month did not have much money to spend but there was no place to go and as a result the software store almost invariably raked in the Army man’s wages. Passing travelers also helps well the sutler income.

The system was a poor one, and the cause of continuous complaint. The soldier, at times was victimized both by high prices in shoddy material. At one juncture soldier resentment in Camp Cady passed the usual grumbling stage and the garrison simply looted the store.

Looting did not satisfy the enraged soldiery. They set fire to the store and literally drove the hated sutler from the camp. The sutler came to San Bernardino and swore out complaints. That was in August 1867 after Camp Cady was manned by regulars.

First Lieut. Manual Eyre Jr. in command at Cady, reported the affair to first Lieut. C. H. Shepherd, assistant adjutant general at Fort Mojave. He said:

“Yesterday the sheriff was here and took with him five of my men for preliminary examination under charges of arson and robbery. The case is stated in my letter addressed to a AAAG at your headquarters, dated August 8, 1867. I should, I think, be in San Bernardino during the trial of these men, if they are held for trial. I also desire to present before the grand jury’s citizens who have harbored deserters.

“The posted by you till will be established under superintendence of an officer from Mojave. Could not an officer be spared temporarily to relieved Lieut. Drum and allow him to relieve me for 10 days or two weeks? If the Rock Springs garrison is withdrawn, I can leave Lieut. Drum here in command until my return?

“The intention of this man Dead (the sutler) is evident to me. He will try to obtain money from these men to let them off. If so, I would like to be present to prosecute him for attempting to compound a felony. I am of the opinion that, as much as I dislike it, I should be in San Bernardino as soon as possible, even if the men are released after preliminary examination when, of course they would be turned loose 100 miles from camp to find their way as they see fit.”

Both because it served as a headquarters post, and because it was maintained long after the little way stations along the Old Government Road were abandoned, Fort Mojave is far better known than such points as Fort Piute, Rock Springs, Marl Spring, Fort Soda, Bitter Spring, Resting Springs or even Cady.

Until recent years Fort Mojave was maintained as an Indian school. When it ceased to be an army post, however, it is records were moved. Some were taken to Whipple barracks in Prescott, others to the Presidio at San Francisco. For Mojave, however had a wealth of old records that escaped attention of the detail entrusted to their moving. Within the past few years the grounds of the old fort were converted to agricultural use. The remains of an old adobe building were bulldozed flat. In the process the bulldozer broke through an old wooden floor long covered with several inches of earth. The accident disclosed a long forgotten cellar. In it were scores of packing boxes containing more records. These were assembled and shipped to Washington. Stacked in a line these rediscovered records stretch 29 feet.

As yet this latest ” mine” of Pioneer Army records has not been made available to historical researchers. Presumably in a few years, however, they will have been cleaned, indexed and deposited in the national archives and will furnish a far more detailed commentary on conditions in the Southwest during the pre-railroad decades,, and on Army activities at a dozen or more all but forgotten published such as Las Vegas, Resting Springs, El Dorado Canyon, and numerous early Arizona camps. Frequent transfers of headquarters seem to have made Fort Mojave a convenient depository for numerous papers no one wanted to which, under regulations, could not be destroyed. Paperwork in the military was almost as involved in the mid-19th century as it is today. Doubtless the company clerk of the Battalion Sgt. major of 1867 rebelled inwardly at the detail required of his job and doubtless to adjutants were hard put to find storage space for the growing mountains of paper but to their credit it must be noted they observed the rules and did not indulge in the periodic bonfires that mark some of the other branches of the federal service. For instance, research on Colorado River steamers is difficult because the customs offices of registry made it a practice to destroy old records.