Historical Timeline

Pre-1776: Willow Springs was a lifeline in the Mojave Desert for centuries. Natural springs made it a vital rest stop for Native peoples, wildlife, and early travelers crossing the dry high desert.

1776: Spanish missionary Francisco Garcés passed through the area and noted the springs in his journals. It was the first known written record of Willow Springs.

1844: Explorer John C. Frémont camped here under the shady willows during one of his expeditions. Back then, this little water source was one of the few dependable spots in the region.

1850: Members of the Jayhawker and Bennett-Arcan parties, who had gotten lost trying to cross Death Valley, stumbled upon Willow Springs. It saved their lives.

1860s: As silver poured out of Cerro Gordo and other desert mines, freight wagons and stagecoaches made Willow Springs a key stop. It was a desert pit stop for the booming mineral trade.

1862: Nelson and Adelia Ward settled near the springs and built an adobe inn, affectionately known as the “Hotel de Rush” because of the nonstop stream of guests needing food, shelter, and water.

1864–1872: The stage lines between Los Angeles and Havilah regularly stopped here. The little station at Willow Springs was part of the high desert’s transportation backbone.

1875: The Riley family was running the station when bandits — remnants of the Tiburcio Vásquez gang — staged a robbery. Crime rode the trails, too.

1900: Ezra “Struck-it-Rich” Hamilton bought the land and springs, hoping to support his mining ventures with the water. He saw more than just dust and rock — he saw a future.

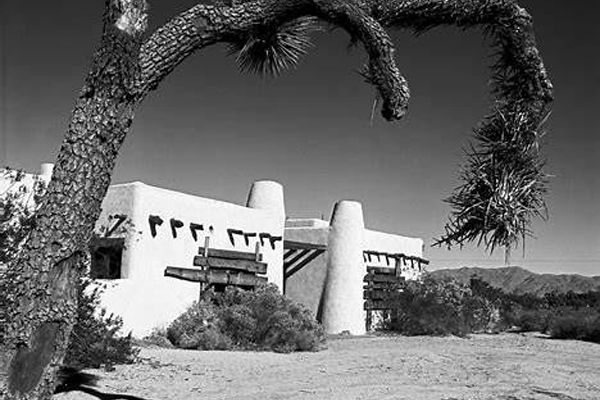

1904: Hamilton poured more than $40,000 into building a resort town. He built 27 stone buildings: a hotel, a school, a swimming pool, and more. For a while, Willow Springs buzzed with promise.

1909–1918: The community had its own post office — a mark of stability and connection to the wider world.

1915: After Hamilton died, interest in the resort faded, and the land changed hands. Without his leadership, the town began to fade.

1952: The Tehachapi earthquake damaged several of the original stone buildings and shook up what was left of the settlement.

1953: Just down the road, Willow Springs International Raceway opened. It became the oldest permanent road racing facility in the U.S. and drew drivers and car lovers from all over.

1962: Bill Huth bought the raceway and turned it into a hotspot for motorsports, hosting countless events over the years.

1996: The raceway was officially recognized as a California Point of Historical Interest — a nod to its unique role in racing history.

2015: Bill Huth passed away, but his family kept the raceway running, honoring his legacy.

2024: The Huth family put Willow Springs Raceway up for sale, possibly closing a major chapter in California motorsports history.

Present Day: The original springs have dried up, but the name and the stories remain. The ruins of Ezra Hamilton’s stone resort still stand, and the engines’ roar echoes from the track nearby. Willow Springs is where desert survival, gold rush dreams, and racing legends all intersect.