Settlers and Seekers in the Mojave Desert

The Mojave Desert has always been a land of extremes—of survival and ambition, of quiet persistence and sudden booms. Two cornerstone texts help tell this story: “Pioneer of the Mojave” by Richard D. Thompson and “Desert Fever” by Vredenburgh, Harthill, and Shumway. Though they cover different periods and perspectives, together they trace the transformation of the Mojave from a sparse frontier to an industrialized desert landscape.

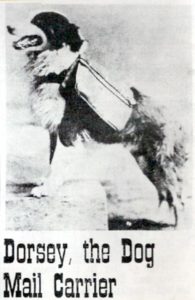

Pioneer of the Mojave introduces us to Aaron G. Lane, one of the first permanent settlers along the Mojave River in the 1850s. His crossing became a lifeline for travelers, freighters, and military expeditions. Lane’s story represents the early days, when survival hinged on access to water, good judgment, and cooperation with those passing through. His efforts in agriculture, trade, and hospitality helped anchor the Mojave as something more than space on a map.

But the story doesn’t end with the settlement.

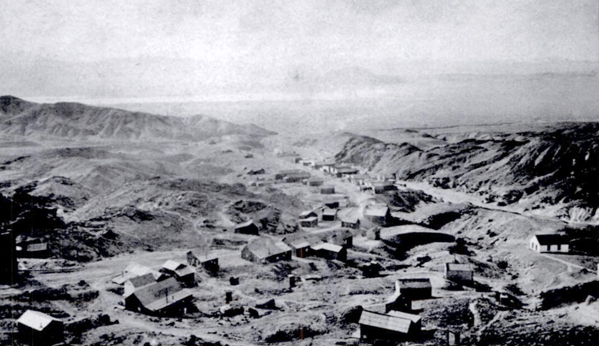

Desert Fever picks up where the pioneers left off, charting the feverish rush for gold, silver, borax, and copper that swept across the California desert in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Boomtowns sprang up where campsites once stood. Trail stops like Daggett and Calico became freight hubs. Water from the Mojave River—once used to grow alfalfa—was now hauled to stamp mills and ore crushers.

Both books share the same landscape, but their characters have different goals. Lane and his peers sought stability. The miners and speculators who came later chased their fortunes, often leaving ghost towns in their wake. What links them is the land itself—unforgiving but full of possibility.

By exploring both books side by side, we see the Mojave Desert not just as a backdrop but as a central character in its own evolving history.

Suggested Section Links (for below this intro):

- Pioneer of the Mojave → [Link to your Lane’s Crossing or full PDF/summary]

- Desert Fever → [Link to chapter index or embedded content]

- Related topics: [Mojave River history], [Daggett], [Panamint City], [Mining in the Mojave]