Little Lake, California:

Little Lake is a small, spring-fed lake tucked between volcanic cliffs and a red cinder cone along California’s Highway 395. To most modern travelers, it’s just a quick blur on the drive north through the high desert. But beneath its quiet surface lies a deep and layered past—one shaped by ancient peoples, rugged prospectors, and enterprising families who turned this desert watering hole into a hub of life and legend.

A Desert Legacy Thousands of Years Old

Long before roads or railroads existed, Little Lake served as a seasonal home to Native American groups that lived and moved throughout the Mojave and Great Basin deserts. Archaeological findings suggest that humans camped here as far back as 10,000 years ago, drawn to the dependable water and abundant resources.

Rock art etched into the black basalt cliffs tells part of this story. Petroglyphs depict figures with atlatls, mountain sheep, and human forms, suggesting the spiritual and practical aspects of these early people’s lives. Over the centuries, different cultural traditions passed through, but one of the most important was the Pinto Culture. This group lived in the region several thousand years ago and left behind signature dart points and evidence of circular house foundations—some of the oldest in California.

Among the most intriguing discoveries is the so-called “Pinto Man,” a human burial found in a shallow grave near the lake, buried with a stone point. Excavations also revealed beads, tools, and a vast amount of obsidian flakes—remnants from toolmaking that still litter the ground today. The presence of local obsidian sources made Little Lake a crucial location for the production and trade of stone tools throughout the Southwest.

Lagunita and the Stagecoach Years

In the 1860s, Little Lake gained new importance. Mexican prospectors called it “Lagunita”—meaning “little lagoon”—as it offered the first fresh water after a dry stretch when traveling north from Indian Wells. When the Cerro Gordo mines boomed in the Eastern Sierra, Little Lake became a natural stop along the Visalia-to-Independence stage line.

A stone station was built here to water horses and rest travelers heading to and from the silver mines. Wagons loaded with ore, mail, and supplies rolled through regularly, and the station saw steady use for over a decade. Its reputation was such that, for many years, it remained untouched by bandits. Folklore tells of the infamous outlaw Tiburcio Vasquez sparing the station out of gratitude.

However, that peace was broken in 1875 when Vasquez was captured and executed. Shortly afterward, one of his lieutenants led a group of bandits to Little Lake, robbing the station and tying up the staff. It was the only known robbery during the stop’s operation—and a sign that times were changing. Within weeks, a new stage route bypassed Little Lake, and the old stone station was left to the wind and sun.

The Railroad Arrives

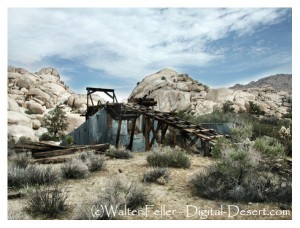

At the turn of the 20th century, Little Lake stirred back to life. Homesteaders like Charles Whittock filed claims and set up adobe ranch houses on the lake’s shore. In 1910, the Southern Pacific Railroad extended its tracks through the area, laying them across the marsh on wooden trestles. A small station was established, and a community began to take shape.

With the railroad came more people—workers, ranchers, and travelers. The growing village eventually took the name “Little Lake,” and a post office opened to serve the community. A few homes, a store, and a small hotel clustered near the tracks. When automobile travel expanded, Little Lake became a convenient stop for early motorists navigating the desert roads.

Bramlette’s Desert Resort

In the early 1920s, a man named William Bramlette saw potential in the quiet lakefront. An auto racer-turned-developer, Bramlette, purchased the land and the old buildings. He dammed the lake’s outlet to deepen the water and cleared the tule reeds. To control vegetation, he released muskrats—an idea that didn’t work out as hoped—but the result was a mile-long lake that could support fishing and boating.

Bramlette built a two-story lodge from concrete and native stone. The Little Lake Hotel, completed in 1923, became the centerpiece of a desert resort. He added a café, general store, service station, and cabins for guests. The lake was stocked with bass and crappie, and Southern Californians came in droves to fish, swim, and escape the city heat. Duck hunters found Little Lake especially inviting during the fall migration, and a private duck club was soon established.

For decades, the Bramlettes ran a bustling operation. The lava rock lodge became a landmark along the highway. Highway 6, later renamed U.S. 395, brought families, fishermen, and outdoor enthusiasts. Children played under cottonwoods while travelers dined, refueled, or stayed the night before continuing north.

Volcanoes, Waterfalls, and Ancient Trails

Little Lake is situated in a dramatic geological setting. The dark cliffs along the lake are ancient basalt flows from volcanic activity that occurred long ago. Just north of the lake lies Fossil Falls—a deep, sculpted gorge carved by meltwater from ancient glaciers. Though dry today, Fossil Falls shows the powerful interaction of water and lava in prehistoric times. Red Hill, a vivid cinder cone, stands nearby, a reminder of more recent eruptions.

The obsidian found around Little Lake originates from local volcanic domes and has been traced to campsites across the western desert. This made Little Lake part of a much larger trade and migration network for Indigenous peoples who came for the toolstone, water, and seasonal game.

Decline and Quiet Legacy

By the 1950s, Little Lake began to fade. In 1958, Highway 395 was rerouted to bypass the village. Traffic and business dropped. The railroad fell out of use and was abandoned by 1981. The Little Lake Hotel remained for several more decades, but after a devastating fire in 1989, it was never rebuilt. The post office closed in 1997, marking the end of permanent settlement.

Today, Little Lake is privately owned and used primarily as a wildlife refuge and seasonal hunting preserve. The lake continues to host migratory waterfowl and serves as habitat for fish and other wildlife. Archaeological protections ensure that its ancient history will not be lost. Occasionally, researchers and rock art enthusiasts visit the area under guided conditions to study its cultural treasures.

Though few structures remain, the spirit of Little Lake endures. It’s a place where volcanic forces and human stories meet—where early desert peoples chipped tools from obsidian, where stagecoaches stopped under the stars, and where modern families once came to fish and rest.

Little Lake may be quiet now, but its story runs deep, etched into stone, whispered in the wind, and remembered by those who still seek out the desert’s hidden corners.