The Death Valley Railroad (DVRR) was a short-line narrow-gauge railroad built to support borax mining in one of the harshest and most remote regions of the American West. Though just 20 miles long, it played a major role in the borax industry during the early 20th century.

Origins and Purpose (1914):

The DVRR was built in 1914 by the Pacific Coast Borax Company, which was transitioning from using massive twenty-mule teams to more efficient rail transportation. The railroad connected the mining town of Ryan, California, located on the western slope of the Funeral Mountains, with the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad at Death Valley Junction, just across the border in Nevada. This made it easier to haul borax out of the desert and get it to market.

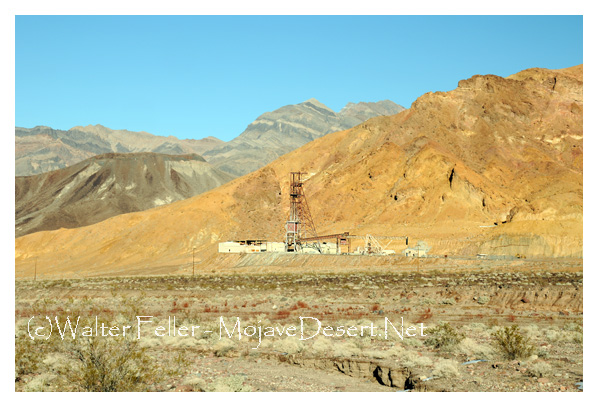

Construction and Equipment:

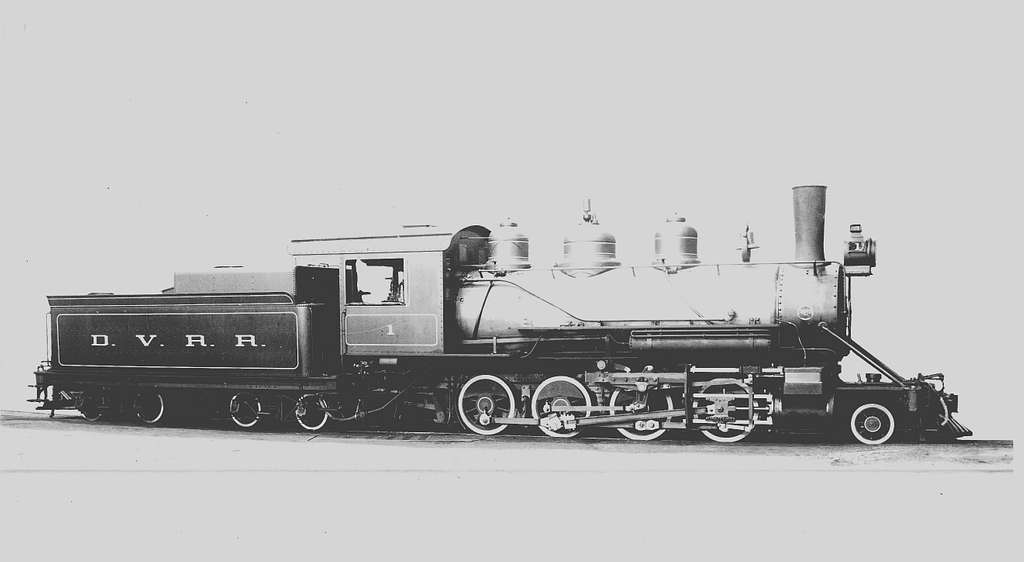

The line was narrow gauge (3 feet wide), which made it easier to build in the rugged terrain of Death Valley. The DVRR used two Baldwin-built 2-8-0 “Consolidation” type steam locomotives—No. 1 (built in 1914) and No. 2 (built in 1916)—which pulled ore cars loaded with borates from the mines at Ryan to Death Valley Junction. From there, the Tonopah & Tidewater carried the loads further to the mainline railroads.

Working Conditions:

Life along the DVRR wasn’t easy. The heat was intense, water was scarce, and the terrain unforgiving. Workers lived in company housing at Ryan, where the Pacific Coast Borax Company built a full company town—complete with school, post office, and even a movie theater.

Decline and Closure (1930):

By 1928, the main borax mine at Ryan was exhausted, and by 1930, the DVRR was officially shut down. The equipment, including locomotives and rolling stock, was sold to the United States Potash Company in New Mexico, where they were used in similar work until the 1950s.

Legacy:

Though it operated for only 16 years, the Death Valley Railroad represents a key transition in the desert’s industrial history—from mule teams to steam power. The railbed can still be traced in places, and some of the original structures at Ryan still stand. Today, Locomotive No. 2 is preserved at the Borax Museum in Furnace Creek, while No. 1 is on display in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

The DVRR was a brief but vital chapter in the saga of mining in Death Valley—a rugged little line that conquered heat, grade, and distance in service to the white gold of the desert.