It was the morning of the hottest day

the thick, warm, air began to weigh

heavy on God’s creatures one and all . . .

. . . so they hugged the shadows however small

and found a hole to scurry in

before the hottest day would begin.

Goodies that may or may not be true facts, somewhat exaggerated, or even wild-eyed stories. You be the judge.

I was out one day by wherever it is I was and shooting photos of the ‘this stuff’ and ‘that stuff’ out there and here comes this near-perfect little Volkswagen beetle. This car is just humming along, then all of a sudden it pulls over and this old guy asks where he can get some old-fashioned film developed. “Is there any place that still does that?” It took me a second (I’ve been shooting digital since the mid-90s) then I said “Walgreens” and that was kind of an ‘Aha’ moment.

So we start talking and I find out this guy was an engineer on the aqueduct and he would survey elevations along the channel because the ground moves nearly continually out there in the far western part of the Mojave. It doesn’t move much but if the water in the aqueduct breaches the side it could get nasty and catastrophic and such. This was so engineers could regulate the flow and all that.

We talk more. After a bit longer I find out this guy is Hugh Hefner’s first cousin. I think that is so cool and I mention the Baseball Hall of Famer Bob “Rapid Robert” Feller is my grandfather’s first cousin. That’s the best I got. He said he does not own a television. I ask if he reads a lot, is a writer or artist or how he stays occupied? He answered me with, “my equations.” How cool is that? So what he likes to do to relax is to try to work out cold fusion. I told him I like to take pictures and tell stupid jokes. And that is the day I met Hugh Hefner’s Cousin

Finding my first fossil was a much bigger deal than I thought it would have been. There was a lot of excitement and yelling. Running around, too–don’t know why, I mean, it wasn’t going anywhere. There were people from the museums, also. They were standing over in the shade grumbling in muffled mumbles. They coveted the find. However, smiling broadly with all rows of their sharpened teeth showing, they stood next to it for pictures.

In a little more than a whisper from their dark huddle, one could hear, “It should have been us. We are worthy.”

Elmer Long’s place — Historic Route 66 – Helendale, Ca.

Then there were the “Northers,” which the heavy winds that swept down the Cajon Pass from the Mohave desert were called. They were much more severe then and sometimes very cold, blowing for about three days at a time. Many people treated them as they would rainy weather, and by way of derision, they were sometimes called “Mormon rains,” coming as they did by way of San Bernardino. They often came before the rains and when sheep had been pastured in the early summer the surface of the ground was cut into fine dust and we would have a dust storm which would cover the inside of the houses with dust. Since the land was planted and roads oiled, the “Northers” have lost most of their disagreeable features. Being dry they clear the atmosphere and are one of the beneficial features in our healthy climate.

History of San Bernardino County – John Brown Jr., 1922

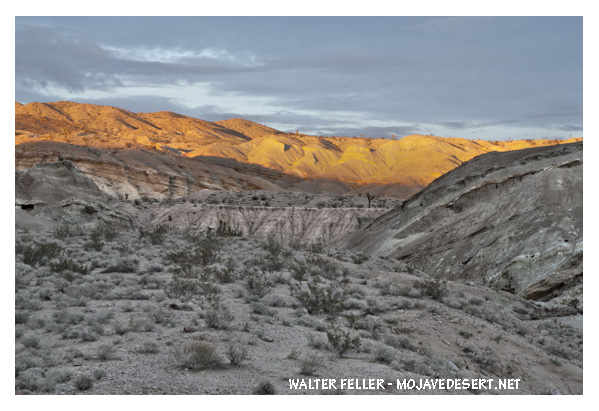

“It is often said that America has no real deserts. This is true in the sense that there are no regions such as are found in Asia and Africa where one can travel a hundred miles at a stretch and scarcely see a sign of vegetation—nothing but barren gravel, graceful, wavy sand dunes, hard, wind-swept clay, or still harder rock salt broken into rough blocks with upturned edges. In the broader sense of the term, however, America has an abundance of deserts—regions which bear a thin cover of bushy vegetation but are too dry for agriculture without irrigation…. In the United States the deserts lie almost wholly between the Sierra Nevada and the Rocky Mountain ranges, which keep out any moisture that might come from either the west or the east. Beginning on the north with the sagebrush plateau of southern Washington, the desert expands to a width of seven hundred miles in the gray, sage-covered basins of Nevada and Utah. In southern California and Arizona the sagebrush gives place to smaller forms like the salt-bush, and the desert assumes a sterner aspect. Next comes the cactus desert extending from Arizona far south into Mexico. One of the notable features of the desert is the extreme heat of certain portions. Close to the Nevada border in southern California, Death Valley, 250 feet below sea-level, is the hottest place in America. There alone among the American regions familiar to the writer does one have the feeling of intense, overpowering aridity which prevails so often in the deserts of Arabia and Central Asia. Some years ago a Weather Bureau thermometer was installed in Death Valley at Furnace Creek, where the only flowing water in more than a hundred miles supports a depressing little ranch. There one or two white men, helped by a few Indians, raise alfalfa, which they sell at exorbitant prices to deluded prospectors searching for riches which they never find. Though the terrible heat ruins the health of the white men in a year or two, so that they have to move away, they have succeeded in keeping a thermometer record for some years. No other properly exposed out-of-door thermometer in the United States, or perhaps in the world, is so familiar with a temperature of 100° F. or more. During the period of not quite fifteen hundred days from the spring of 1911 to May, 1915, a maximum temperature of 100° F. or more was reached in five hundred and forty-eight days, or more than one-third of the time. On July 10, 1913, the mercury rose to 134° F. and touched the top of the tube. How much higher it might have gone no one can tell. That day marks the limit of temperature yet reached in this country according to official records. In the summer of 1914 there was one night when the thermometer dropped only to 114° F., having been 128° F. at noon. The branches of a pepper-tree whose roots had been freshly watered wilted as a flower wilts when broken from the stalk.”

—The Chronicles of America.—Volume I. “The Red Man’s Continent,” by Ellsworth Huntington.

Millie was undeniably beautiful. She was quite clever also. She developed a system wherein she could chop wood without lifting a finger. Living at the post office and only store for miles around, she became quite astute at knowing when the cowboys and other such young men would be coming to pick up supplies and mail. She would study the dust coming off the roads in the distance. Seeing this she would walk over to the woodpile, take up her ax, and ineffectively swing it in a feigned attempt to split firewood as her happy victims arrived. She would sigh. What buck could resist? A delightful young lady, an ax, and a pile of wood needing splitting was just what a young man would need to impress and earn her attention. Before too long, a cord of expertly prepared firewood would be neatly stacked ready for cooking and heating.

-Walter Feller

by Bret Harte –

Francis Brett Hart, known as Bret Harte (August 25, 1836 – May 5, 1902), was an American short story writer and poet, best remembered for his short fiction featuring miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold Rush.

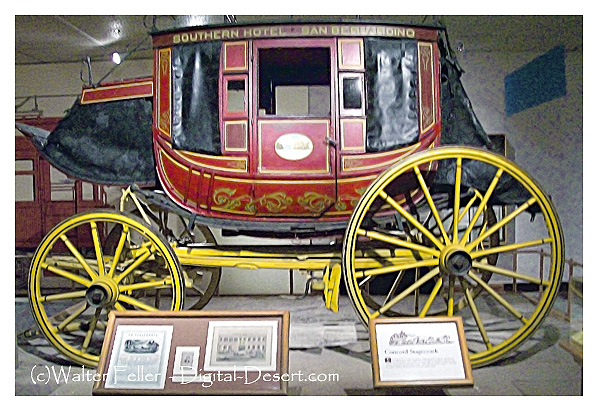

I stood with my shawl and carpetbag in hand, gazing doubtingly on the vehicle. Even in the darkness the red dust of Wingdam was visible on its roof and sides, and the red slime of Slumgullion clung tenaciously to its wheels. I opened the door; the stage creaked easily, and in the gloomy abyss the swaying straps beckoned me, like ghostly hands, to come in now and have my sufferings out at once.

I must not omit to mention the occurrence of a circumstance which struck me as appalling and mysterious. A lounger on the steps of the hotel, who I had reason to suppose was not in any way connected with the stage company, gravely descended, and walking toward the conveyance, tried the handle of the door, opened it, expectorated in the carriage, and returned to the hotel with a serious demeanor. Hardly had he resumed his position when another individual, equally disinterested, impassively walked down the steps, proceeded to the back of the stage, lifted it, expectorated carefully on the axle, and returned slowly and pensively to the hotel. A third spectator wearily disengaged himself from one of the Ionic columns of the portico and walked to the box, remained for a moment in serious and expectorative contemplation of the boot, and then returned to his column. There was something so weird in this baptism that I grew quite nervous.

Perhaps I was out of spirits. A number of infinitesimal annoyances, winding up with the resolute persistency of the clerk at the stage office to enter my name misspelt on the waybill, had not predisposed me to cheerfulness. The inmates of the Eureka House, from a social viewpoint, were not attractive. There was the prevailing opinion–so common to many honest people–that a serious style of deportment and conduct toward a stranger indicates high gentility and elevated station. Obeying this principle, all hilarity ceased on my entrance to supper, and general remark merged into the safer and uncompromising chronicle of several bad cases of diphtheria, then epidemic at Wingdam. When I left the dining-room, with an odd feeling that I had been supping exclusively on mustard and tea leaves, I stopped a moment at the parlor door. A piano, harmoniously related to the dinner bell, tinkled responsive to a diffident and uncertain touch. On the white wall the shadow of an old and sharp profile was bending over several symmetrical and shadowy curls. “I sez to Mariar, Mariar, sez I, ‘Praise to the face is open disgrace.'” I heard no more. Dreading some susceptibility to sincere expression on the subject of female loveliness, I walked away, checking the compliment that otherwise might have risen unbidden to my lips, and have brought shame and sorrow to the household.

It was with the memory of these experiences resting heavily upon me that I stood hesitatingly before the stage door. The driver, about to mount, was for a moment illuminated by the open door of the hotel. He had the wearied look which was the distinguishing expression of Wingdam. Satisfied that I was properly waybilled and receipted for, he took no further notice of me. I looked longingly at the box seat, but he did not respond to the appeal. I flung my carpetbag into the chasm, dived recklessly after it, and–before I was fairly seated–with a great sigh, a creaking of unwilling springs, complaining bolts, and harshly expostulating axle, we moved away. Rather the hotel door slipped behind, the sound of the piano sank to rest, and the night and its shadows moved solemnly upon us.

To say it was dark expressed but faintly the pitchy obscurity that encompassed the vehicle. The roadside trees were scarcely distinguishable as deeper masses of shadow; I knew them only by the peculiar sodden odor that from time to time sluggishly flowed in at the open window as we rolled by. We proceeded slowly; so leisurely that, leaning from the carriage, I more than once detected the fragrant sigh of some astonished cow, whose ruminating repose upon the highway we had ruthlessly disturbed. But in the darkness our progress, more the guidance of some mysterious instinct than any apparent volition of our own, gave an indefinable charm of security to our journey that a moment’s hesitation or indecision on the part of the driver would have destroyed.

I had indulged a hope that in the empty vehicle I might obtain that rest so often denied me in its crowded condition. It was a weak delusion. When I stretched out my limbs it was only to find that the ordinary conveniences for making several people distinctly uncomfortable were distributed throughout my individual frame. At last, resting my arms on the straps, by dint of much gymnastic effort I became sufficiently composed to be aware of a more refined species of torture. The springs of the stage, rising and falling regularly, produced a rhythmical beat which began to absorb my attention painfully. Slowly this thumping merged into a senseless echo of the mysterious female of the hotel parlor, and shaped itself into this awful and benumbing axiom–“Praise-to-the-face-is- open-disgrace. Praise-to-the-face-is-open-disgrace.” Inequalities of the road only quickened its utterance or drawled it to an exasperating length.

It was of no use to consider the statement seriously. It was of no use to except to it indignantly. It was of no use to recall the many instances where praise to the face had redounded to the everlasting honor of praiser and bepraised; of no use to dwell sentimentally on modest genius and courage lifted up and strengthened by open commendation; of no use to except to the mysterious female, to picture her as rearing a thin-blooded generation on selfish and mechanically repeated axioms–all this failed to counteract the monotonous repetition of this sentence. There was nothing to do but to give in–and I was about to accept it weakly, as we too often treat other illusions of darkness and necessity, for the time being, when I became aware of some other annoyance that had been forcing itself upon me for the last few moments. How quiet the driver was!

Was there any driver? Had I any reason to suppose that he was not lying gagged and bound on the roadside, and the highwayman with blackened face who did the thing so quietly driving me–whither? The thing is perfectly feasible. And what is this fancy now being jolted out of me? A story? It’s of no use to keep it back– particularly in this abysmal vehicle, and here it comes: I am a Marquis–a French Marquis; French, because the peerage is not so well known, and the country is better adapted to romantic incident– a Marquis, because the democratic reader delights in the nobility. My name is something LIGNY. I am coming from Paris to my country seat at St. Germain. It is a dark night, and I fall asleep and tell my honest coachman, Andre, not to disturb me, and dream of an angel. The carriage at last stops at the chateau. It is so dark that when I alight I do not recognize the face of the footman who holds the carriage door. But what of that?–PESTE! I am heavy with sleep. The same obscurity also hides the old familiar indecencies of the statues on the terrace; but there is a door, and it opens and shuts behind me smartly. Then I find myself in a trap, in the presence of the brigand who has quietly gagged poor Andre and conducted the carriage thither. There is nothing for me to do, as a gallant French Marquis, but to say, “PARBLEU!” draw my rapier, and die valorously! I am found a week or two after outside a deserted cabaret near the barrier, with a hole through my ruffled linen and my pockets stripped. No; on second thoughts, I am rescued–rescued by the angel I have been dreaming of, who is the assumed daughter of the brigand but the real daughter of an intimate friend.

Looking from the window again, in the vain hope of distinguishing the driver, I found my eyes were growing accustomed to the darkness. I could see the distant horizon, defined by India-inky woods, relieving a lighter sky. A few stars widely spaced in this picture glimmered sadly. I noticed again the infinite depth of patient sorrow in their serene faces; and I hope that the vandal who first applied the flippant “twinkle” to them may not be driven melancholy-mad by their reproachful eyes. I noticed again the mystic charm of space that imparts a sense of individual solitude to each integer of the densest constellation, involving the smallest star with immeasurable loneliness. Something of this calm and solitude crept over me, and I dozed in my gloomy cavern. When I awoke the full moon was rising. Seen from my window, it had an indescribably unreal and theatrical effect. It was the full moon of NORMA–that remarkable celestial phenomenon which rises so palpably to a hushed audience and a sublime andante chorus, until the CASTA DIVA is sung–the “inconstant moon” that then and thereafter remains fixed in the heavens as though it were a part of the solar system inaugurated by Joshua. Again the white-robed Druids filed past me, again I saw that improbable mistletoe cut from that impossible oak, and again cold chills ran down my back with the first strain of the recitative. The thumping springs essayed to beat time, and the private-box-like obscurity of the vehicle lent a cheap enchantment to the view. But it was a vast improvement upon my past experience, and I hugged the fond delusion.

My fears for the driver were dissipated with the rising moon. A familiar sound had assured me of his presence in the full possession of at least one of his most important functions. Frequent and full expectoration convinced me that his lips were as yet not sealed by the gag of highwaymen, and soothed my anxious ear. With this load lifted from my mind, and assisted by the mild presence of Diana, who left, as when she visited Endymion, much of her splendor outside my cavern–I looked around the empty vehicle. On the forward seat lay a woman’s hairpin. I picked it up with an interest that, however, soon abated. There was no scent of the roses to cling to it still, not even of hair oil. No bend or twist in its rigid angles betrayed any trait of its wearer’s character. I tried to think that it might have been “Mariar’s.” I tried to imagine that, confining the symmetrical curls of that girl, it might have heard the soft compliments whispered in her ears which provoked the wrath of the aged female. But in vain. It was reticent and unswerving in its upright fidelity, and at last slipped listlessly through my fingers.

I had dozed repeatedly–waked on the threshold of oblivion by contact with some of the angles of the coach, and feeling that I was unconsciously assuming, in imitation of a humble insect of my childish recollection, that spherical shape which could best resist those impressions, when I perceived that the moon, riding high in the heavens, had begun to separate the formless masses of the shadowy landscape. Trees isolated, in clumps and assemblages, changed places before my window. The sharp outlines of the distant hills came back, as in daylight, but little softened in the dry, cold, dewless air of a California summer night. I was wondering how late it was, and thinking that if the horses of the night traveled as slowly as the team before us, Faustus might have been spared his agonizing prayer, when a sudden spasm of activity attacked my driver. A succession of whip-snappings, like a pack of Chinese crackers, broke from the box before me. The stage leaped forward, and when I could pick myself from under the seat, a long white building had in some mysterious way rolled before my window. It must be Slumgullion! As I descended from the stage I addressed the driver:

“I thought you changed horses on the road?”

“So we did. Two hours ago.”

“That’s odd. I didn’t notice it.”

“Must have been asleep, sir. Hope you had a pleasant nap. Bully place for a nice quiet snooze–empty stage, sir!”

–

We can speak of the unholy Wind

and no matter how clever or articulate,

the Wind may censure our little voice.

It was time to choose the first people. Everyone gathered to make their pleas and arguments. Rabbit’s ideas were mean and stupid. Rabbit wanted to be the first people. He became angry and kicked a large rock into the river changing its course. This is how the Virgin River came to meet the Colorado. . . . And why we are not rabbits.- Paiute legend

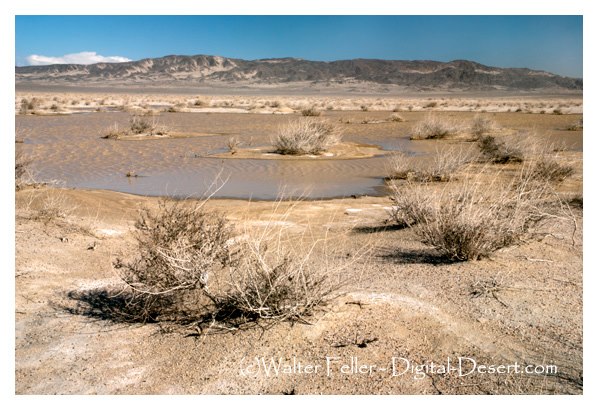

Virgin River

https://digital-desert.com/virgin-river/

Old ‘Long’ Johnson sat in his rocker on the porch whittling a stick thinking about the time he saved Nell from certain doom. ‘Dubious’ Dan had tied her to a log at the sawmill and she was just about ready to be cut in half the long way when Old ‘Long’ Johnson saved the day for her. Another time Old ‘Long’ Johnson saved Nell’s life her was when ‘Left-handed’ Larry tied her to the railroad track to be ran over by the 9:18. Old ‘Long’ Johnson was there at 9:17 to cut her loose. One other time Nell had been tied up by Steve the ‘Scuz’ and thrown in the river. Old ‘Long’ Johnson fetched her safely out just before she would have crossed the point of no return and went over the edge at Certain Death Falls. “Seemed as if no one liked Nell,” thought Old ‘Long’ Johnson. “She was quite mouthy.”

– The End –

. . . or is it just the beginning?

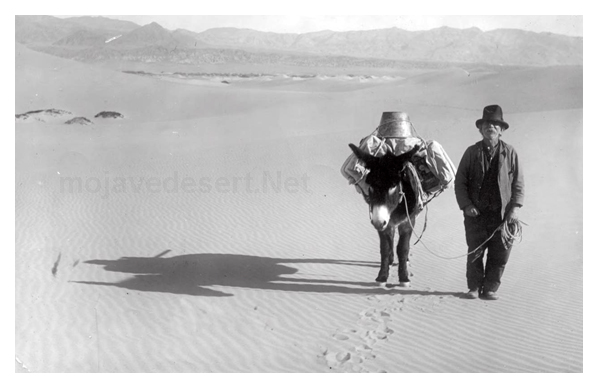

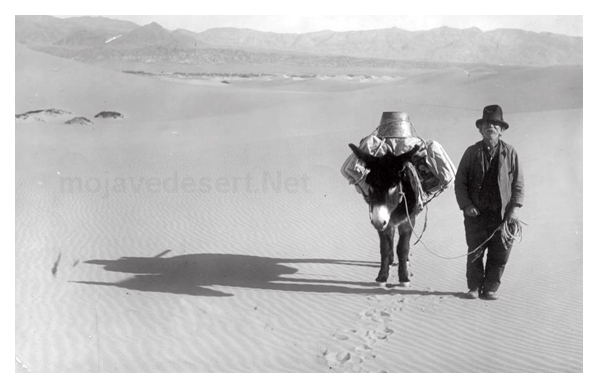

A gentleman named Bill had a hankering to wander about the desert. He had been told the way to really see the desert was to walk through it. He liked the idea and drove as far as Death Valley to start a good distance from all humanity and all things civilized. Here he met a Shoshone Indian Chief who traded him a fine burro for a fine, fairly new car. Off he went for a wonderful, if not occasionally harrowing adventure. Through Nevada into a corner of Utah back into Arizona and down the north rim of the Grand Canyon and back up the south rim to the village and then back to the desert in California. Well over a year had passed when he returned to his wife who was waiting for him in the little town of Baker in the middle of the Mojave. All was well upon his return and his adventures were becoming known far and wide. Bill had become known as ‘Burro’ Bill. One evening there was a knock at the door. Bill was surprised to see his friend, the Shoshone chief. The chief wanted his burro back. ‘Burro’ Bill said the burro was his now. They had been through so much together and he could not bear to part with the beast. The chief explained that a day or two after Bill and the burro departed the car had a flat tire and broke a wheel therefore was not drivable, therefore the deal was no good. The burro was still operable while the car that sat in Death Valley was not.

ref: review

Burro Bill and Me, Ramblings in the American Desert

Author: Edna Calkins Price

Bill owned a chicken ranch out in the great wide-open desert. He was called to go to the big city to do some business and would be gone for several weeks. He asked his friend, Buck, to watch his chicken ranch while he was gone. Buck accepted and each and every day he fed and watered the chickens and gathered the eggs.

One day a rainy deluge swept across the desert causing flash flooding, panic, and havoc. The runoff from the rain destroyed all the chicken feed on Bill’s ranch. Since it would be a while before Bill returned, Buck was in a bit of a fix over the chicken feed. Buck went into the little town nearby to buy some more. He needed two sacks of feed but could only afford one. Buck, being the resourceful individual that he was, went next door to the lumber mill and bought a sack of sawdust. By mixing the sawdust with the chicken feed he would have enough to feed the chickens and keep them from starving.

Buck’s plan appeared to work, but soon one of the chickens laid a wooden egg–and then another hen laid one, and there was another, and another, and another.

When Bill returned from the big city all of his chickens were laying wooden eggs.

Now, everybody pretty much knows that wooden eggs are useless and it didn’t take but a minute or so for Bill to realize the predicament he was in.

Bill solved his problem by getting out of the egg business.

The end.

From: Edward Fitzgerald Beale, a Pioneer in the Path of Empire, 1822-1903

The water of Little Salt Lake is as briny, we were told, like that of Great Salt Lake, and we noticed that its shores were covered with saline incrustations for a mile or more from the water’s edge; but the Mormons stated that the salt was of little value, being impregnated with saleratus and other alkaline matter, which rendered it unfit for use. They obtain their supplies of this article from mines of rock salt in the mountains. The excitement occasioned by the threats of Walkah, the Utah chief, continued to increase during the day we spent at Parowan. Families flocked in from Paragoona, and other small settlements and farms, bringing with them their movables, and their flocks and herds. Parties of mounted men, well-armed, patrolled the country; expresses came in from different quarters, bringing accounts of attacks by the Indians, on small parties and unprotected farms and houses. During our stay, Walkah sent in a polite message to Colonel G. A. Smith, who had military command of the district, and governed it by martial law, telling him that, “The Mormons were d—d fools for abandoning their houses and towns, for he did not intend to molest them there, as it was his intention to confine his depredations to their cattle, and that he advised them to return and mind their crops, for, if they neglected them, they would starve, and be obliged to leave the country, which was not what he desired, for then there would be no cattle for him to take.” He ended by declaring war for four years. This message did not tend to allay the fears of the Mormons, who, in this district, were mostly foreigners, and stood in great awe of Indians.

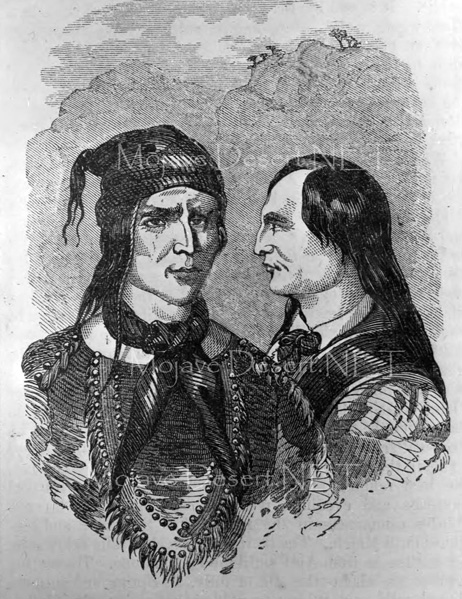

The Utah chieftain who occasioned all this panic and excitement is a man of great subtlety and indomitable energy. He is not a Utah by birth but has acquired such an extraordinary ascendency over that tribe by his daring exploits, that all the restless spirits and ambitious young warriors in it have joined his standard. Having an unlimited supply of fine horses, and being inured to every fatigue and privation, he keeps the territories of New Mexico and Utah, the provinces of Chihuahua and Sonora, and the southern portion of California in constant alarm. His movements are so rapid, and his plans so skillfully and so secretly laid, that he has never once failed in any enterprise and has scarcely disappeared from one district before he is heard of in another. He frequently divides his men into two or more bands, which making their appearance at different points at the same time, each headed, it is given out, by the dreaded Walkah in person, has given him, with the ignorant Mexicans, the attribute of ubiquity. The principal object of his forays is to drive off horses and cattle, but more particularly the first, and among the Utahs we noticed horses with brands familiar to us in New Mexico and California.

This chief had a brother as valiant and crafty as himself to whom he was greatly attached. Both speaking Spanish and broken English they were enabled to maintain intercourse with the whites without the aid of an interpreter. This brother the Mormons thought they had killed, for, having repelled a night attack on a mill, which was led by him, on the next morning they found a rifle and a hatchet which they recognized as his, and also traces of blood and tracks of men apparently carrying a heavy body. Although rejoicing at the death of one of their most implacable enemies, the Mormons dreaded the wrath of the great chieftain, which they felt would not be appeased until he had avenged his brother’s blood in their own. The Mormons were surprised at our having passed in safety through Walkah’s territory, and they did not know to what they were to attribute their escape from destruction. They told us that the cattle tracks which we had seen a few days previously were those of a portion of a large drove lifted by Walkah, and that the mounted men we had noticed in the mountains in the evening of August 1st were scouts sent out by him to watch our movements. They endeavored to dissuade us from prosecuting our journey, for they stated that it was unsafe to travel even between their towns without an escort of from twenty-five to thirty men.

He has adopted the name of Walker (corrupted to Walkah) on account of the close intimacy and friendship which in former days united him to Joe Walker, an old mountaineer, and the same who discovered Walker’s Pass in the Sierra Nevada.

The Mormons had published a reward of fifteen thousand dollars for Walkah’s head, but it was a serious question among them who should “bell the cat.”

After a down pouring rain water had collected in a small natural basin the sticks and stems and twigs and dried up flowers had fermented into an intoxicating brew that the local desert fauna seemed to enjoy drinking. There was what turned into a drunken festival in which the hare, sloppily and completely boozed up challenged a tee-totaling tortoise to a race. The tortoise, who was not too bright, accepted the contest mainly because the rabbit was staggering about insulting the clutch of eggs the sober tortoise hatched from and complaining that the whole tortoise famn-damily was slow and stupid.

Bobcats and rats and mice and snakes and lizards and coyotes put aside their differences to watch the tiny marathon and gathered together at the starting line. The judge, a badger, got a gun from somewhere and wildly fired it toward the sky and a batch of drunken Canada geese that happened to be flying by, winging one but not quite killing it, only making it wish it were dead from the pain. And that was the start of the race.

The hare bolted and leaped sideways rather uncontrollably as if one hind leg were much shorter than the other–he rocketed into a patch of California Buckwheat (eriogonum fasciculatum) and fell over. The tortoise, who calculated the rabbit was too stoned to follow the course, felt that if he were slow and steady and persistent, that he could beat the rabbit.

A bit later, the rabbit passed the tortoise faster than the tortoise had ever seen a rabbit move. However, the tortoise continued to believe that if he were slow and steady and persistent, that he could beat the rabbit and sure enough, the tortoise plugged along and quietly passed the rabbit taking a nap under a desert willow (chilopsis linearis). The tortoise smugly snickered as he passed the hungover hare.

The tortoise kept its pace and crossed the finish line proudly proclaiming that he had won the race. Judge Badger, with his gun in claw, fired it into the air hitting another flying goose then walked right up to the tortoise and said, “didn’t you see the rabbit? He went back to tell you you lost.” The embarrassed tortoise crawled back to his burrow, entered and slept the rest of the summer and everything else in the animal world went back to normal including the two coyotes that tracked the course back to the still passed out rabbit and ate him.

The end. There is no moral.

S. Wallace Austin – January 26, 1929

The recent death of Wyatt Earp ( January 13, 1929) recalls to mind the part he played in the claim jumping expedition to Searles Lake in October 1910. At the time I was Acting Receiver for the California Trona Company and was in charge of a group of placer mining claims covering some 40,000 acres. The party had been organized at Los Angeles by Henry E. Lee, an Oakland attorney and probably was the best equipped gang of claim jumpers ever assembled in the west. It consisted of three complete crews of surveyors, the necessary helpers and laborers and about 20 armed guards or gunmen under the command of Wyatt Berry Stapp.

The party of 44 in number, arrived at Searles Lake in seven touring cars and established a camp at the abandoned town of “Slate Range City” about eight miles southeast of the company’s headquarters. On the morning following their arrival we saw some of the surveyors across the lake and our foreman road over and ordered them off the property but they paid no attention to his protest an proceeded to do a very thorough job or surveying and staking.

As I considered it necessary to make some show of force in protecting our claims, I visited the enemy’s camp at sunrise the next day with our whole force of five men who were armed with all the weapons they could collect. It was a very critical moment when we jumped from our wagon and walked up in front of the mess house where the raiders were assembled for breakfast. I stood in the center with my boys on either side of me. There was a shout and men came running from all directions and fearing there might be trouble.

I started right off to explain to the surveyors present that I had only come over to give notice that I was officially and legally in possession of the claims and that they were trespassers.

Before I got very far a tall man with iron grey hair and a mustache pushed his way to the front and in a loud voice demanded why I had come into their camp with armed men. At the same time he grabbed hold of my shotgun held by the boy on my left and attempted to take it away from him. At this attack upon us I drew an automatic and ordered him to let go. He did so and then ran to a building nearby saying “I’ll fix you.” Before he could secure a rifle, however, the cooler headed members of the party surrounded him and calmed him down. Also, you may be sure every effort was made to prevent a fight, as, in spite of our bold being, we were pretty badly scared.

Just as things seemed to have quieted down, one of the excited jumpers accidentally discharged a gun. No one was hurt but, it was a very tense moment for all of us. Having failed to dislodge the enemy the following day I called for a US Marshall and when he arrive the claim jumpers were all arrested and sent home including “Wyatt Berry Stapp”, none other than the famous Marshal Wyatt Stapp Earp.

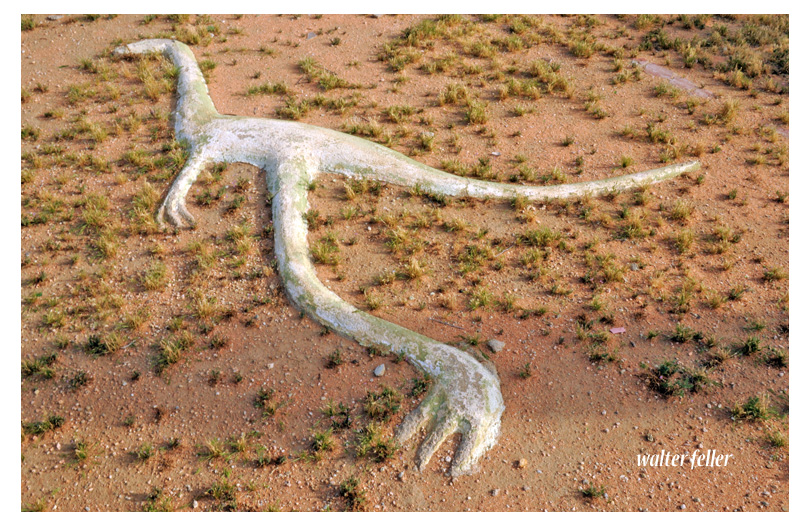

Apple Valley’s Dinosaur Park – by Myra McGinnis

If you drove north on Central Avenue in Apple Valley, about 3 miles from Highway 18, a strange sight might give you a moment surprise: a group of dinosaurs would appear on the horizon. This meant figures represent the work of Lonnie Coffman, a soft-spoken, wiry, energetic man, who, in the 1960s, began the building of his childhood fantasy a dinosaur park.

With his Midwestern family to board to provide recreational trips and entertainment, Coffman spent much of his childhood in the public library reading about prehistoric animals and dreaming of the park he would someday build for other children to enjoy. According to a former neighbor, Rose McHenry, he worked from dawn until dark every day on his hobby. He never charged the busloads of schoolchildren that visited the park, climbing over this meant replicas, and listening to the man, usually of few words, expound on the life of the dinosaur.

He had written to Washington to get the exact measurements of Noah’s Ark to add to his collection, when, after 12 years of personal funding, his savings ran out. Coffman appealed to the county for help to continue building his 17 1/2 acre park, but was turned down. He had no other recourse but to give up his dream. According to Mrs. McHenry, Lonnie Coffman left the area about 1982 a heartbroken man, leaving his concrete dinosaurs to the winds and sands of the desert.

Adapted from Mojave V – Mohahve Historical Society

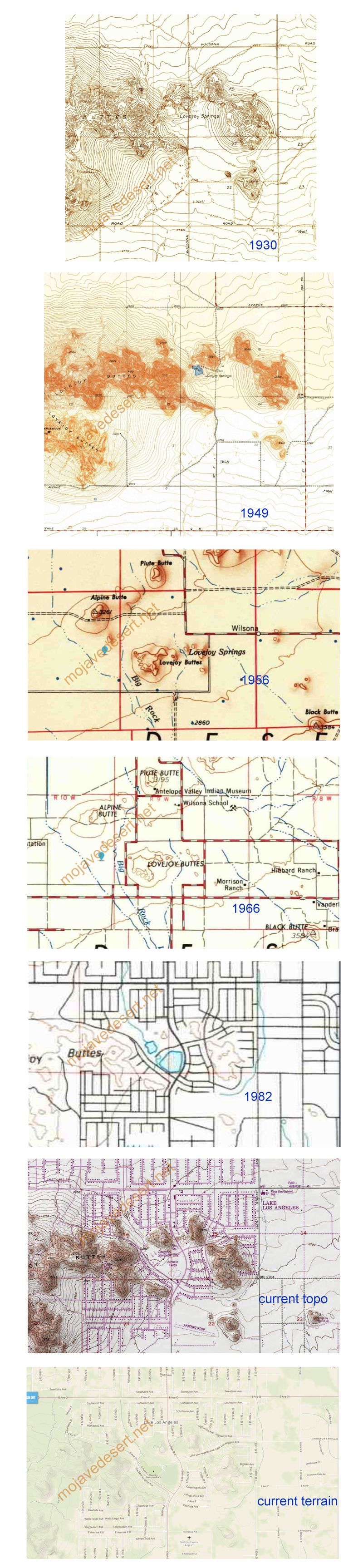

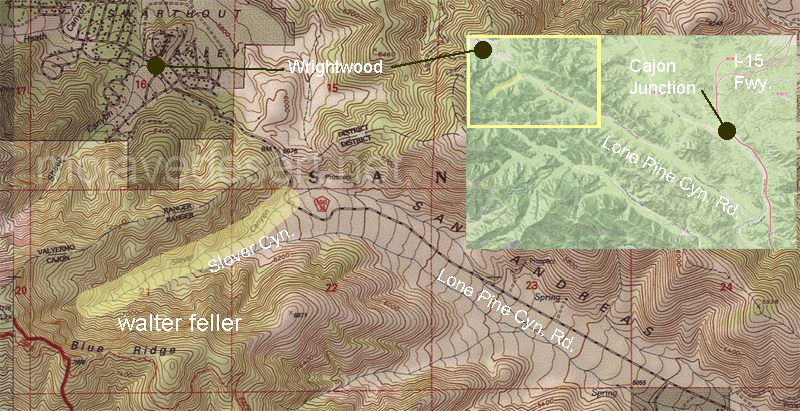

The Story of Lovejoy Springs becoming Lake Los Angeles, in maps …

“I was down in San Berdo the other day, and a man got me into one of them women’s afternoon fandangos; you know, one of them afternoon affairs where they all talk and don’t say nothing. And a “fly-up-the-creek” woman came up, all “a side-winding,” and said: ‘Now Mr. Scott, I’m sure in your desert travels you must have lots of opportunities to do kind deeds. What you tell the ladies the kindest deeds you ever did?”

“Well, lady,” I says, ” let me think a minute. One time several years ago I been traveling all day on a horse, and I came in on a dry camp way up in one of the canyons. There was an old road leading up to it; hadn’t been used for years; but I noticed fresh tracks on it. When I got to the camp, there sat an old man and an old woman. They must have been 70 years old apiece. When they saw me they both began to cry, and I said: ‘ my goodness, how in the hell did you two ever get up here?’ Well, they said, they were driving through the valley, and it was so hot they thought they were going to die, and they come up to this road and they thought it led to a higher place where it would be so hot, so they took it and got up there, and it was night, so they camped there all night in the morning they found their horse had wandered off. They had looked for him but he was gone, and they’d been there most a week and had no food. Well, I open my packet built a fire and made them a cup of coffee and fried some bacon and stirred up some saddle blankets (hot cakes) for them, and say, you ought to see them two old folks eat! It cheered them up considerable.

We sat around the fire all the evening and powwowed, and they was a nice old couple. We all slept that night on the ground. They was pretty cold, so I gave them a blanket I had. The next morning I made them some more coffee and gave them some breakfast. I had to be going, so I packed up and got astride my horse. I sort of hated to leave the old couple; they seemed kind enough sort of people; but there was nothing else to do; so I said goodbye, and they both was crying; said they’d sure die; no way for them to get out. They couldn’t walk. It was 100 miles from help, and there was no automobiles in those days. But I got on my horse and started off, and then I looked around and saw them two old people a-standing there crying, and, you know, I just couldn’t stand it to leave them old people there alone to die, so I’d just took out my rifle and shot them both. Lady, that was the kindest deed I ever did.”

“Oh, Scotty,” I said, “Why did you tell those women such a tale as that?”

“Well, you know all them bandits you meet when you go out; you got to tell them something, ain’t you?”

“I suppose so, but it seems to me you might think up something better than that to tell at a ladies club meeting.”

“Well, that’s what I told that bunch, anyway. You’ve got to send up some kind of a howl if you’re going to be heard. There are so many free schools and so much ignorance.”

And Scotty lighted another fifteen cent cigar (he always smoked the best), …

from Death Valley Scotty by Mabel – Bessie M. Johnson

– Death Valley Natural History Association

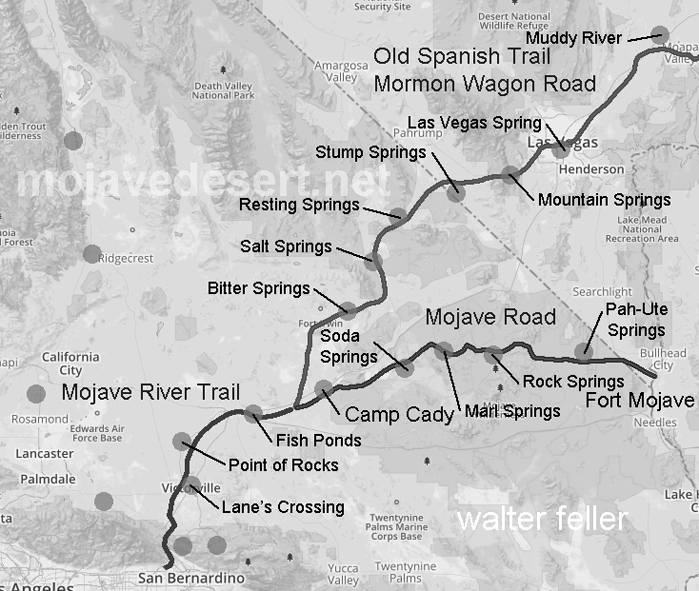

I have heard that the Paiute Indians have a legend–a story they would tell about a giant who crossed the desert with an olla full of water in each arm. With each step he would leave his footprint in the ground, and water would spill from the olla into the hole as he walked on. The giant was so large that these waterholes were one day’s walk between each for a normal-sized man. The Indian learned this and used these waterholes to travel great distances and trade with other Peoples beyond the desert. As time went on and things went the way things do, one such trail became the Mojave Road. — Editor

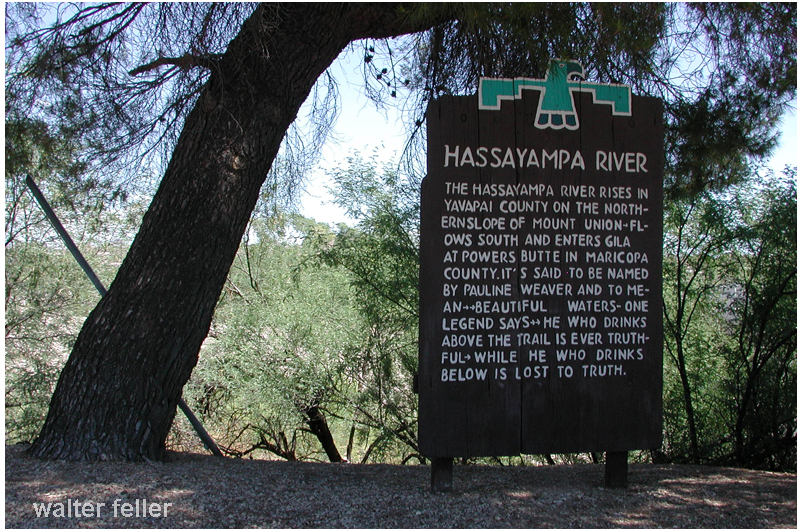

The legend of the Hassayampa River as it runs through Wickenburg, Arizona, has it that if you drink from the river’s waters you will never tell the truth again. There, of course, are some caveats and loopholes some weak-kneed people may use to claim the curse will not affect them, but it does–they may be lying, however.

At any rate, it was not people who went into the desert merely to write it up who invented the fabled Hassayampa, of whose waters, if any drink, they can no more see fact as naked fact, but all radiant with the color of romance. I, who must have drunk of it in my twice seven years’ wanderings, am assured that it is worthwhile.

~ Land of Little Rain – Mary Austin

Country of Lost Borders

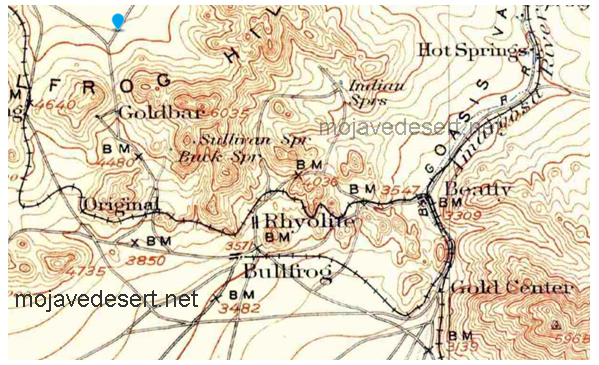

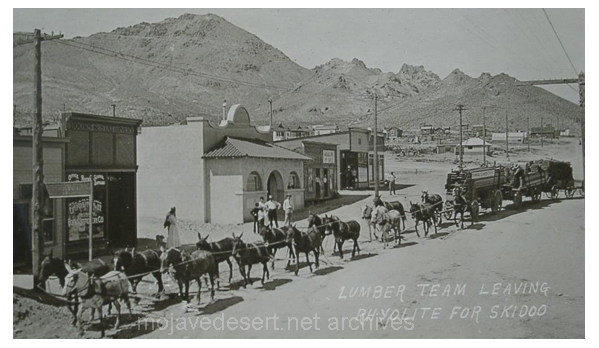

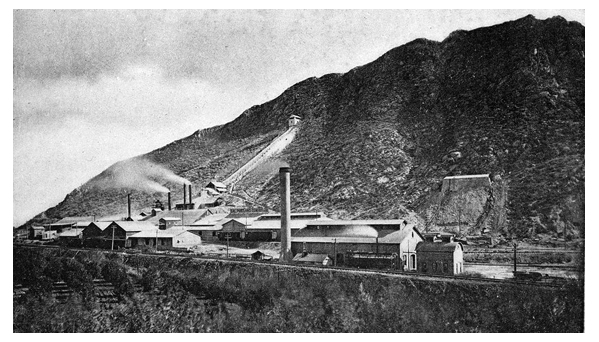

Shorty Harris and his companion eating next to an automobile somewhere in Death Valley during the 1920s. Rhyolite, Nevada was founded in 1904 after Shorty Harris and Ed Cross discovered Rhyolite Quartz at the Bullfrog mine. By 1906 the town had two railroad lines and a population of 10,000. The mines, however, did not produce as expected and by the early 1910s Rhyolite was abandoned. Aurora, Nevada was a silver mining boomtown founded in 1860. The heyday of Aurora ran throughout the 1860s (Mark Twain briefly lived there), but it slowly declined after 1870. It went through a rebirth in 1912 when a new stamp mill and cyanide plant were built at the mines. In 1917, however, the mill closed down and by the early 1920s Aurora was abandoned. Calico, California was initially founded as a silver mining town in 1882 but by 1890 the cost of recovering the silver became prohibitive. The town, however, continued to exist until 1907 due to the production of Borax.

At Furnace Creek ranch, Mr. Harris learned of the finding of three partially decomposed bodies between Lee’s camp in Echo canon and the Lida C. [sic] borax mine, at the foot of a low hill on the north side of the Funeral range. The presence of the bodies was first reported at Ash Meadows by an Indian, who was attracted to the spot by a band of coyotes and a …

The prospector is one of the unique, one of the most exceptional and most worthy of all those remarkable characters who have exploited and led the way for the development of the west. The west owes him a debt of gratitude which the west can never pay. Always poor, often homeless, self-reliant, hopeful, generous and brave, he has been the solitary explorer of desert and mountain vastness. He is the one who unlocked from its imprisoned silence the countless millions of what is now the world’s wealth. He penetrates the most remote and inaccessible regions, defies hunger and storms alike, sleeps upon the mountain side or in improvised cabins, restlessly wanders and searches through weeks and months and years for nature’s hidden and hoarded treasures. Often-times his search ends in poverty and distress and failure, sometimes in success. Without the prospector – this poor isolated wanderer – the great mining centers of the west would not exist. Without his uneasy, never-tiring efforts, millions of dollars now on their way to minister to the happiness and comfort of the country would never have been poured into the channels of business and commerce.

(Excerpt taken from “100 Years of Real Living” by the Bishop Chamber of Commerce, 1961)

The devil wanted a place on earth, sort of a summer home.

A place to spend his vacation whenever he wanted to roam.

So he picked out Barstow, a place both wretched and rough.

Where the climate was to his liking and the people were hardened and tough.

He dried up the streams in the canyons and ordered no rain to fall.

He dried up the lakes in the valley then baked and scorched it all.

Then over his barren desert he transplanted shrubs from hell.

The cactus, thistle and prickly pear. The climate suited them well.

Now, the home was much to his liking, but animal life, he had none.

So he created crawling creatures that all mankind would shun.

First he made the rattlesnake with its forked poisonous tongue;

Taught it to strike and rattle and how to swallow its young.

The he made scorpions and lizards and the ugly old Horned Toad.

He placed spiders of every description under rocks by the side of the road.

The he ordered the sun to shine hotter, hotter and hotter still.

Until even the cactus wilted and the old Horned Toad looked ill.

Then he gazed on his earthly kingdom as any creator would.

He chuckled a little up his sleeve and admitted that it was good.

‘Twas summer now and Satan lay by a prickly pear to rest.

The sweat rolled off his swarthy brow so he took off his coat and vest.

“By Golly,” he finally panted, “I did my job too well, I’m going

Back where I came from. Barstow is hotter than Hell.”

~ Anonymous

-= Mojave River Valley Museum =-

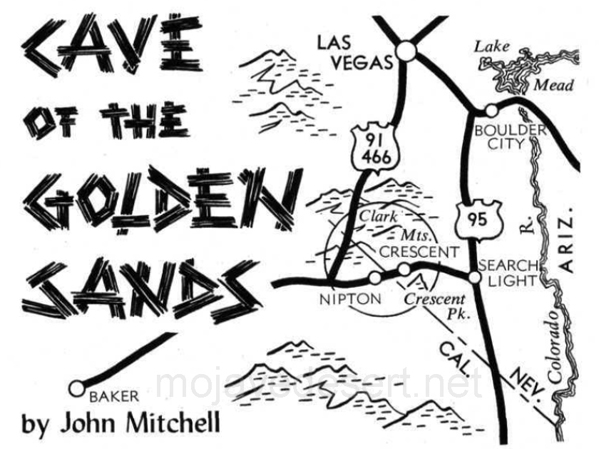

by John Mitchell – Desert Magazine, December 1967

Fifty years ago, about the time the Salt Lake railroad was being built from Salt Lake City to

San Pedro, California, many small mining camps were springing up all along the line and the hills were full of prospectors. An old man with long white whiskers, mounted on a burro and driving four others ahead of him, showed up at the little mining camp of Crescent, Nevada. After watering his burros at the water trough near the windmill he pulled off to one side and made camp. By the time his burros were unpacked and hobbled and the campfire going, Winfield Sherman, Ike Reynolds, Bert Cavanaugh, Jim Wilson and the writer had gathered around to pass the time of day with the newcomer.

During the conversation, which was carried on mostly by Winfield Sherman, a typical long-haired, bewhiskered desert rat, the old prospector volunteered the information that his name was Riley Hatfield, that he hailed from Raleigh, North Carolina, and that he had come out west on the advice of the family doctor. He said he was headed for Searchlight, Nevada, to purchase provisions and to see a doctor about a heart ailment that had been troubling him.

The old man was very polite, had a good outfit and looked prosperous. However, he did not seem to be much interested in the Crescent camp despite the buildup we old-timers had given it while sitting around the campfire.

The old man broke camp shortly after breakfast the next morning and by sunup was headed out over the trail in the direction of Searchlight. Two days later the writer happened to be in Searchlight to pick up mail and provisions and met the prospector at Jack Wheatley’s boarding

house.

After dinner I joined the old man on the front porch for a smoke and a little chat. During the conversation he told me he had some placer gold for sale and asked me if I knew anyone who would buy it. I referred him to the assay office at either the Duplex or Quartette mine. Later that afternoon he told me he had sold the gold at the Duplex assay office. He reached into his pocket and pulled out five or six of the most beautiful gold nuggets I had ever seen. He said he was sending them to a friend.

I saw the prospector several times the following day and late that afternoon he told me he had purchased his supplies and had seen a doctor and would be ready to pull out early the next day. He asked me to accompany him as far as Crescent where I had my own camp.

After breakfast the next morning we headed our two pack outfits in the direction of Crescent Peak 14 miles west.

About noon we stopped for lunch and to give the burros a chance to browse. While the bacon was sizzling and the coffee pot was sputtering the old man told me he had discovered four pounds of gold nuggets in a black sand deposit near the Clark Mountains northeast of

Nippeno (now called Nipton.) He invited me to go with him as he did not like to be out in the desert alone.

He said that one day while camped just below Clark Peak, he climbed a short way up the mountainside and saw off to the east a dry lake bed that suddenly filled with water. It looked so real he could see trees along the shore and their reflection in the water.

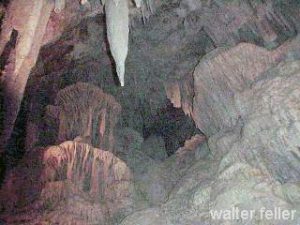

The route he was following to Crescent and Searchlight was in that general direction so he decided to investigate the lake or whatever it was. As he approached the lake later it had entirely disappeared, and he then realized that it was only a beautiful mirage. Fortunately he had brought a good supply of water along. About noon while skirting the western edge of the dry lake bed he saw what seemed to be the entrance to a cave on the east side of a small limestone hill about 50 feet above the level of the dry lake bed.

There is something interesting about a cave. It may contain anything—an iron-bound chest full of gold and silver and precious gems, bandit loot, old guns, saddles, artifacts, bones of man or long extinct animals. I sometimes think this love of the cave has been handed down to us by ancient ancestors who lived in caves. When one of those old-timers headed for his cave two jumps ahead of a three-toed whang-doodle the cave looked good to him.

Likewise this cave looked good to the old prospector and he decided to make camp and explore it. At least it offered shelter from desert sand storms.

The entrance was a long tunnel. He had not gone far inside when he heard the sound of running water. Returning to the mouth of the cave for a lantern, he made his way back along the narrow entrance and soon came to a great dome-shaped chamber resembling an amphitheatre full of churning water. As he stood there a small whirlpool appeared in the center and suddenly the water rushed out with a roar like thunder. The bottom seemed to have dropped out of the cave. The floor was shaped like a large basin with bench-like terraces or

steps that led down to the dark center. The terraces were piled high with black sand that trickled down with the receding water.

Hanging from the ceiling were thousands of beautiful stalactites while other thousands of stalagmites stood up from the floor of the cave. In places they formed massive columns. Around the interior of the cavern were many grottos sparkling with crystals. The walls were

plastered with lime carbonate like tapestries studded with diamonds. Never in his life had he seen anything like it. Above the top terrace was a human skeleton and in a nearby grotto were the bones of some extinct animal, probably a ground sloth.

The center of the basin-shaped bottom of the cave was now filled with black sand that had slid down from the surrounding terraces. On the way out he gathered a few handfuls of the sand

which later was found to be sprinkled with yellow nuggets that gleamed in the desert sunlight. That night the old prospector sat by his campfire smoking and reveling in the dreams of a Monte Cristo. Was he not rich?

According to his story the water in the cavern rises and falls with the ebb and flow of the tides in the Pacific and is active twice every 24 hours. First a rumbling sound like a subterranean cannonading is heard coming from the dark interior and then suddenly the pile of black sand that chokes the tube-like chimney, is seen to rise up, and a dark column of water 18 feet in diameter bulges up from the center and reaches a height of 45 or 50 feet. This dome of

water and sand spreads out into waves and breaks into white spray as it dashes against the terraces. The play or intense agitation keeps up for several hours and then the pool settles down and is quiet as a millpond.

If the old man told the truth about the sand in the lake bed and in the cavern, it would be difficult to compute the value of the gold that could be taken from this cave. Then, too, every time the tide comes it brings up more gold. How far the black stream reaches down the underground stream, I am unable to say.

Our dinner was over by the time the old man had finished his story, and we began to break camp.

He invited me to go along with him to his cave and work with him. This I readily agreed to do as soon as I could sell my mining claims in the Crescent camp. The old man promised to be back in about three weeks with more gold at which time I hoped to be ready to accompany him.

I sold my claim to an old French Canadian named Joe Semenec, who was prospecting for a Dr. John Horsky, of Helena, Montana.

The old prospector never returned and to this date no word has ever come out of the desert as to his fate. I have since learned that an old man with long white whiskers was found dead on the dry lake bed near Ivanpah. He and his burros were shot to death. I do not know if this was the same man or not.

The old man had told me that there was from three to six feet of this heavy black sand on the dry lake bed, which is now covered by a shroud of snow white sand.

Naturally I do not know the exact location of this million dollar cave. If I did I would locate it myself instead of writing this story which will, no doubt, stir interest in that part of the desert. This cave should not be confused with one that recently was discovered out on Highway 91 east of San Bernardino, California, which is said to extend for a distance of eight miles and to contain a fortune in gold.

Some old prospector or desert rat with a magic lamp to transport him to this hole in the ground, could live like a king, if he had enough money to buy a small electric light plant, some rails and an ore car. He could live in a fairy palace with nothing to do but wait for the tide to come in with more gold.

–.–

In December of 1849 anxious gold seekers and their wagons broke away from the Mojave San Joaquin Company (Mojave Sand-walking Company) to take a shortcut to the goldfields of California. Their map was incomplete and vague not informing these wayward pioneers of the numerous ranges of mountains between them and their destination. As a result they lost their way in the rocky canyons and sandy washes leading down into what we now know as Death Valley.

It was obvious to the travelers that Indians lived in the area, but they all had fled from the wanderers with one exception. Both Julia Brier and William Manly, members of this band of Lost 49ers recorded the first known encounter with this remaining Timbisha Shoshone Indian.

The next morning the company moved on over the sand to — nobody knew where. One of the men ahead called out suddenly, “Wolf! Wolf!” and raised his rifle to shoot.

“My God, it’s a man!” his companion cried. As the company came up we found the thing to be an aged Indian lying on his back and buried in the sand — save his head. He was blind, shriveled and bald and looked like a mummy.

He must have been one hundred and fifty years old. The men dug him out and gave him water and food. The poor fellow kept saying, “God bless pickaninnies!” Wherever he had learned that. His tribe must have fled ahead of us and as he couldn’t travel he was left to die.

Excerpt from the December 25, 1898 edition of The San Francisco Call

Our Christmas Amid the Terrors of Death Valley – Julia Brier

The following account of the same incident was written by William Manly in his book, Death Valley in ’49

Next morning I shouldered my gun and followed down the cañon keeping the wagon road, and when half a mile down, at the sink of the sickly stream, I killed a wild goose. This had undoubtedly been attracted here the night before by the light of our camp fire. When I got near the lower end of the cañon, there was a cliff on the north or right hand side which was perpendicular or perhaps a little overhanging, and at the base a cave which had the appearance of being continuously occupied by Indians. As I went on down I saw a very strange looking track upon the ground. There were hand and foot prints as if a human being had crawled upon all fours. As this track reached the valley where the sand had been clean swept by the wind, the tracks became more plain, and the sand had been blown into small hills not over three or four feet high. I followed the track till it led to the top of one of these small hills where a small well-like hole had been dug and in this excavation was a kind of Indian mummy curled up like a dog. He was not dead for I could see him move as he breathed, but his skin looked very much like the surface of a well dried venison ham. I should think by his looks he must be 200 or 300 years old, indeed he might be Adam’s brother and not look any older than he did. He was evidently crippled. A climate which would preserve for many days or weeks the carcass of an ox so that an eatable round stake could be cut from it, might perhaps preserve a live man for a longer period than would be believed.

~ Love that disparate history 🙂

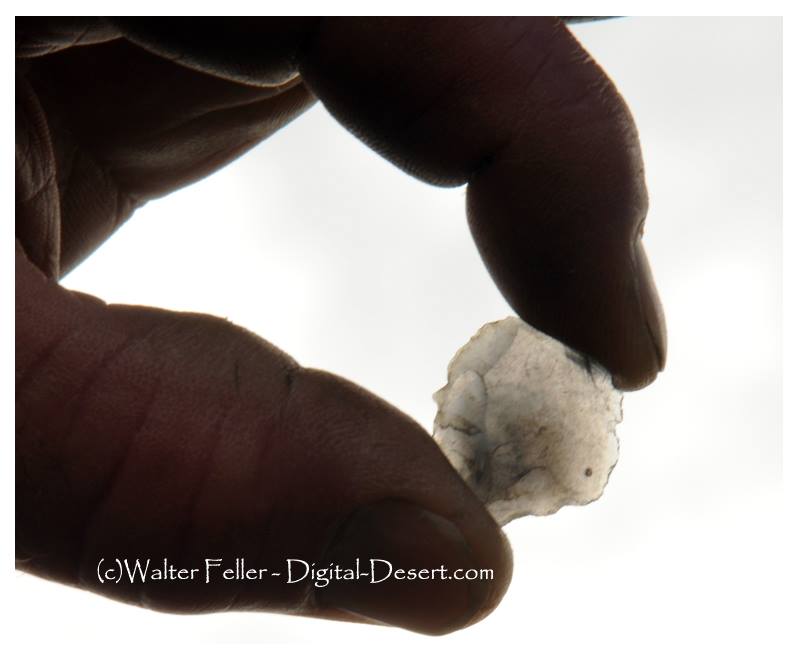

I suppose the cool thing about this flake is that it was found in a little spot in a large meadow at the bottom of a valley in a local mountain range hundreds of miles from the closest source of obsidian. This may mean it was part of a trade or series of trades between Indian groups maybe even thousands of years ago. With each trade, with each mile from the source the rock that this flake was part of became more and more valuable. With each trade the material became more precious and smaller flakes like this, which may have been discarded as debitage closer to the source, but used for smaller items and valued the further the distance away.

This flake was found in what could have been an ancient campfire, or fire pit as there was countless bit of charcoal the same color as the little rock. The difference in texture made the piece standout from the charcoal. The gentleman that found this noticed this difference from his experience, developing an eye for these types of relics while I stood there spacing out at the beautiful scenery. He held it up to the light so I could snap a picture showing its translucence. Amazing to me. He flipped it up into the air like a coin–it landed back on the midden. Then we went somewhere else.

from: Half a Century Chasing Rainbows

By Frank "Shorty" Harris as told to Phillip Johnston

Touring Topics: Magazine of the American Automobile Association of Southern California - October 1930

The best strike I ever made was in 1904 when I discovered the Rhyolite and Bullfrog district. I went into Boundary Canyon with five burros and plenty of grub, figuring to look over the country northeast from there. When I stopped at Keane Wonder Mine, Ed Cross was there waiting for his partner, Frank Howard, to bring some supplies from the inside. For some reason, Howard had been delayed, and Cross was low on grub.

“Shorty,” he said, “I’m up against it, and the Lord knows when Howard will come back. How are the chances of going with you?”

“Sure, come right along,” I told him, “I’ve got enough to keep us eating for a couple of months.”

So we left the Keane Wonder, went through Boundary Canyon, and made camp at Buck Springs, five miles from a ranch on the Amargosa where a squaw man by the name of Monte Beatty lived. The next morning while Ed was cooking, I went after the burros. They were feeding on the side of a mountain near our camp and about half a mile from the spring. I carried my pick, as all prospectors do, even when they are looking for their jacks—a man never knows just when he is going to locate pay-ore. When I reached the burros, they were right on the spot where the Bullfrog mine was afterward located. Two hundred feet away was a ledge of rock with some copper stains on it. I walked over and broke off a piece with my pick—and gosh, I couldn’t believe my own eyes. The chunks of gold were so big that I could see them at arm’s length—regular jewelry stone! In fact, a lot of that ore was sent to jewelers in this country and England, and they set it in rings, it was that pretty! Right then, it seemed to me that the whole mountain was gold.

I let out a yell, and Ed knew something had happened; so he came running up as fast as he could. When he got close enough to hear, I yelled again: “Ed we’ve got the world by the tail, or else we’re coppered!”

We broke off several more pieces, and they were like the first—just lousy with gold. The rock was green, almost like turquoise, spotted with big chunks of yellow metal, and looked a lot like the back of a frog. This gave us an idea for naming our claim, so we called it the Bullfrog. The formation had a good dip, too. It looked like a real fissure vein; the kind that goes deep and has lots of real stuff in it. We hunted over the mountain for more outcroppings, but there were no other like that one the burros led me to. We had tumbled into the cream pitcher on the first one—so why waste time looking for skimmed milk?

That night we built a hot fire with greasewood, and melted the gold out of the specimens. We wanted to see how much was copper, and how much was the real stuff. And when the pan got red hot, and the gold ran out and formed a button, we knew that our strike was a big one, and that we were rich.

“How many claims do you figure on staking out?” Ed asked me.

“One ought to be plenty,” I told him. “If there ain’t enough in one claim, there ain’t enough in the whole country. If other fellows put extensions on that claim of ours, and find good stuff, it will help us sell out for big money.”

Ed saw that that was a good argument, so he agreed with me.

After the monuments were placed, we got some more rich samples and went to the county seat to record our claim. Then we marched into Goldfield, and went to an eating-house. Ed finished his meal before I did, and went out into the street where he met Bob Montgomery, a miner that both of us knew. Ed showed him a sample of our ore, and Bob couldn’t believe his eyes.

“Where did you get that?” he asked.

“Shorty and I found a ledge of it southwest of Bill Beatty’s ranch,” Ed told him.

Bob thought he was having some fun with him and said so.

“Oh, that’s just a piece of float that you picked up somewhere. It’s damn seldom ledges like that are found!”

Just then I came walking up, and Ed said, “Ask Shorty if I ain’t telling you the truth.”

“Bob,” I said, “that’s the biggest strike made since Goldfield was found. If you’ve got any sense at all, you’ll go down there as fast as you can, and get in on the ground floor!”

That seemed to be proof enough for him, and he went away in a hurry to get his outfit together—one horse and a cart to haul his tools and grub. He had an Indian with him by the name of Shoshone Johnny, who was a good prospector. Later on, it was this Indian who set the monuments on the claim that was to become the famous Montgomery-Shoshone Mine.

It’s a might strange thing how fast the news of a strike travels. You can go into a town after you’ve made one, meet a friend on the street, take him into your hotel room and lock the door. Then, after he has taken a nip from your bottle, you can whisper the news very softly in his ear. Before you can get out on the street, you’ll see men running around like excited ants that have had a handful of sugar poured on their nest. Ed and I didn’t try to keep our strike a secret, but we were surprised by how the news of it spread. Men swarmed around us and asked to see our specimens. They took one look at them, and then started off on the run to get their outfits together.

I’ve seen some gold rushes in my time that were hummers, but nothing like that stampede. Men were leaving town in a steady stream with buckboards, buggies, wagons, and burros. It looked like the whole population of Goldfield was trying to move at once. Miners who were working for the big companies dropped their tools and got ready to leave town in a hurry. Timekeepers and clerks, waiters and cooks—they all got he fever and milled around, wild-eyed, trying to find a way to get out to the new “strike.” In a little while, there wasn’t a horse or wagon in town, outside of a few owned by the big companies, and the price of burros took a big jump. I saw one man who was about ready to cry because he couldn’t buy a jackass for $500.

A lot of fellows loaded their stuff on two-wheeled carts—grub, tools, and cooking utensils, and away they went across the desert, two or three pulling a cart and the pots and pans rattling. When all the carts were gone, men who didn’t have anything else started out on that seventy-five-mile hike with wheelbarrows; and a lot of ’em made it alright—but they had a hell of a time!

When Ed and I got back to our claim a week later, more than a thousand men were camped around it, and they were coming in every day. A few had tents, but most of ‘em were in open camps. One man had brought a wagon load of whiskey, pitched a tent, and made a bar by laying a plank across two barrels. He was serving the liquor in tin cups, and doing a fine business.

That was the start of Rhyolite, and from then on things moved so fast that it made even us old-timers dizzy. Men were swarming all over the mountains like ants, staking out claims, digging and blasting, and hurrying back to the county seat to record their holdings. There were extensions on all sides of our claim, and other claims covering the country in all directions.

In a few days, wagon loads of lumber began to arrive, and the first buildings were put up. These were called rag-houses because they were half boards and half-canvas. But this building material was so expensive that lots of men made dugouts, which didn’t cost much more than plenty of sweat and blisters.

When the engineers and promoters began to come out, Ed and I got offers every day for our claim. But we just sat tight and watched the camp grow. We knew the price would go up after some of the others started to ship bullion. And as time went on, we saw that we were right. Frame shacks went up in the place of rag-houses and stores, saloons, and dance halls were being opened every day.

Bids for our property got better and better. The man who wanted to buy would treat me with plenty of liquor before he talked business, and in that way, I got all I wanted to drink without spending a bean. Ed was wiser, though, and let the stuff alone—and it paid him to do it too, for when he did sell, he got much more for his half than I got for mine.

One night, when I was pretty well lit up, a man by the name of Bryan took me to his room and put me to bed. The next morning, when I woke up, I had a bad headache and wanted more liquor. Bryan had left several bottles of whiskey on a chair beside the bed and locked the door. I helped myself and went back to sleep. That was the start of the longest jag I ever went on; it lasted six days. When I came to, Bryan showed me a bill of sale for the Bullfrog, and the price was only $25,000. I got plenty sore, but it didn’t do any good. There was my signature on the paper and beside it, the signatures of seven witnesses and the notary’s seal. And I felt a lot worse when I found out that Ed had been paid a hundred and twenty-five thousand for his half, and had lit right out for Lone Pine, where he got married. Today he’s living in San Diego County, has a fine ranch, and is very well fixed.

As soon as I got the money, I went out for a good time. All the girls ate regularly while old Shorty had the dough. As long as my stake lasted I could move and keep the band playing. And friends—I never knew I had so many! They’d jam a saloon to the doors, and every round of drinks cost me thirty or forty dollars. I’d have gone clean through the pay in a few weeks if Dave Driscol hadn’t given me hell. Dave and I had been partners in Colorado and Utah, and I thought a great deal of him. Today he’s living over in Wildrose Canyon and going blind. Well, I had seven or eight thousand left when Dave talked to me.

“Shorty,” he said, “If you don’t cut this out you’ll be broke in a damn short time and won’t have the price of a meal ticket!”

I saw that he was right, and jumped on the water wagon then and there—and I haven’t fallen off since.

Rhyolite grew like a mushroom. Gold Center was started four miles away, and Beatty’s ranch became a town within a few months. There were 12,000 people in the three places, and two railroads were built out to Rhyolite. Shipments of gold were made every day, and some of the ore was so rich that it was sent by express with armed guards. And then a lot of cash came into Rhyolite—more than went out from the mines. It was this sucker money that put the town on the map quickly. The stock exchange was doing a big business, and I remember that the price of Montgomery-Shoshone got up to ten dollars a share.

Businessmen of Rhyolite were live ones, alright. They decided to make the town the finest in Nevada—and they came mighty near doing it. Overbury built a three-story office building out of cut stone—it must have cost him fifty thousand. The bank building had three stories too, and the bank was finished with marble and bronze. There were plenty of other fine business houses and a railroad station that would look mighty good in any city.

Money was easy to get and easy to spend in those days. The miners and muckers threw it right and left when they had it. Many a time I’ve seen ‘em eating bacon and beans, and drinking champagne. Wages were just a sideline with them—most of their money was made in mining stock.

Rhyolite was a great town, and no mistake—as live as the Colorado camps were thirty years before, but not so bad. We had a few gunfights, and several tough characters got their light shot out, which didn’t make the rest of us sore. We were glad enough to spare ‘em. I saw some of those fights myself, but I never took any part in the fireworks. “Shorty, the foot racer” was what they called me because I always ducked around the corner when the bullets began to fly. I knew they were not meant for me, but I wasn’t taking any chances.

There was plenty of gold in those mountains when I discovered the original Bullfrog, and there’s plenty there yet. A lot of it was taken out while Rhyolite was going strong—$6,000,000 or $7,000,000—but they quit before they got the best of it. Stock speculation—that’s what killed Rhyolite! The promoters got impatient. They figured that money could be made faster by getting gold from the pockets of suckers than by digging it out of the hills. And so, when the operators of the Montgomery-Shoshone had a little trouble; when they ran into the water and struck a sulfite ore which is refractory and has to be cut and roasted to be turned into money—the bottom dropped out of the stock market and the town busted wide open, She died quick, too. Most of the tin horns lit out for other parts, and that’s a sure sign a mining camp is going on the rocks.

If the right people ever got hold of Rhyolite they’ll make a killing, but they’ll have to be really hard rock miners and not the kind that does their work only on paper. Rhyolite is dead now—dead as she was before I made the big strike. Those fine buildings are standing out there on the desert, with the coyotes and jackrabbits playing hide and seek around them.

-|-

from: Half a Century Chasing Rainbows

By Frank “Shorty” Harris as told to Phillip Johnston

Touring Topics: Magazine of the American Automobile Association of Southern California

October 1930

Don Pablo further stated that he knew Cristobal Slover very well; was a neighbor of his where they lived with the New Mexican colonists just south of Slover Mountain in Agua Mansa; this mountain took its name from him; he was buried at its southern base, but no mark is there to show his grave. He killed the bear and the bear killed him was the brief summary of the last bear hunt this Rocky Mountain hunter and trapper was in; he wounded the grizzly, then followed him into a dense brush thicket where the bear got him.

Cristobal Slover (Isaac Slover), the noted hunter and trapper of the Rocky Mountains, settled with his wife Dona Barbarita, at the south end of what is now known as Slover Mountain, near Colton, San Bernardino County, about the year 1842. He belonged to that class of adventurous pioneers who piloted the way blazing the trails, meeting the Indian, the grizzly, the swollen rivers, the vast deserts, and precipitous mountains, all kinds of trials, privations, and dangers in opening the way for others to follow and establish on these Western shores a civilization the nation can be proud of.

In the book entitled “Medium of the Rockies,” written by his old Rocky Mountain companion, John Brown, Sr., may be found a brief and interesting historical reference to Mr. Slover in the simple and exact words of the author which are here given: “A party of fur trappers, of whom I was one, erected a fort on the Arkansas River in Colorado, for protection, and as headquarters during the winter season. We called it ‘Pueblo.’ The City of Pueblo now stands upon that ground. Into this fort, Cristobal Slover came one day with two mules loaded with beaver skins. He was engaged to help me supply the camp with game, and during the winter we hunted together, killing buffalo, elk, antelope, and deer, and found him a reliable and experienced hunter. He was a quiet, peaceable man, very reserved. He would heed no warning and accept no advice as to his methods of hunting. His great ambition was to kill grizzlies—he called them ‘Cabibs.’ He would leave our camp and be gone for weeks at a time without anyone knowing his whereabouts, and at last he did not return at all, and I lost sight of him for several years.

“When I came to San Bernardino in 1852 I heard of a man named Slover about six miles southwest from San Bernardino, at the south base of the mountain that now bears his name, so I went down to satisfy my mind who this Slover was and to my great surprise here I again met my old Rocky Mountain hunter, Cristobal Slover, and his faithful wife. Dona Barbarita. We visited one another often and talked about our experiences at Fort Pueblo and of our other companions there James W. Waters, V. J. Herring, Alex Godey, Kit Carson. Bill Williams, Fitzpatrick, Bridger, Bill Bent, the Sublette and others, and where they had gone, and what had become of them.

“Mr. Slover’s head was now white, but his heart was full of affection. He took my family to his home and made us all welcome to what he had. His wife and mine became as intimate as two sisters, and frequently came to visit us.

“He never forgot his chief enjoyment in pursuing the grizzly; when no one else would go hunting with him he would go alone into the mountains, although his friends warned him of the danger.

“One day he went with his companion. Bill McMines, up the left fork of the Cajon Pass almost to the summit where he came across a large grizzly and Slover fired at close range. The bear fell but soon rose and crawled away and laid down in some oak brush. Slover after re-loading his rifle began approaching the monster in spite of the objection of McMines. As the experienced bear hunter reached the brush the bear gave a sudden spring and fell on Mr. Slover, tearing him almost to pieces. That ended his bear hunting. Frequently the most expert hunters take too many chances, as was the case this time. McMines came down the mountain and told the tale, and a party went back and cautiously approached the spot; found the bear dead, but Slover still breathing but insensible. He was brought down to Sycamore Grove on a rude litter and there died. The scalp was torn from his head, his legs and one arm broken, the whole body bruised and torn. He was taken to his home and buried between his adobe house and the mountain the spot was not marked, or if so has rotted away so that I have been unable to locate the grave after searching for it, so to place a stone to mark the resting place of my old Rocky Mountain associate, Cristobal Slover, as I have brought from Cajon Pass a granite rock and placed it at the grave of my other companion, V. J. Herring, more familiarly known as “Uncle Rube.” My other Rocky Mountain companion, James W. Waters, more familiarly known as “Uncle Jim,” has also passed on ahead of me and has a fine monument to mark his resting place adjoining my family lot, where I hope to be placed near him when I am called from earth, both of us near our kindred for whom we labored many years on earth.”

Brown, John Jr., and James Boyd. History of San Bernardino and Riverside Counties. Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois: 1922.

Also see: