Desert Magazine – Feb. 1967

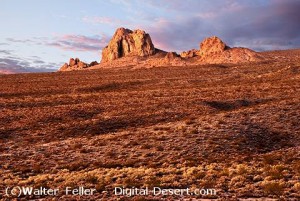

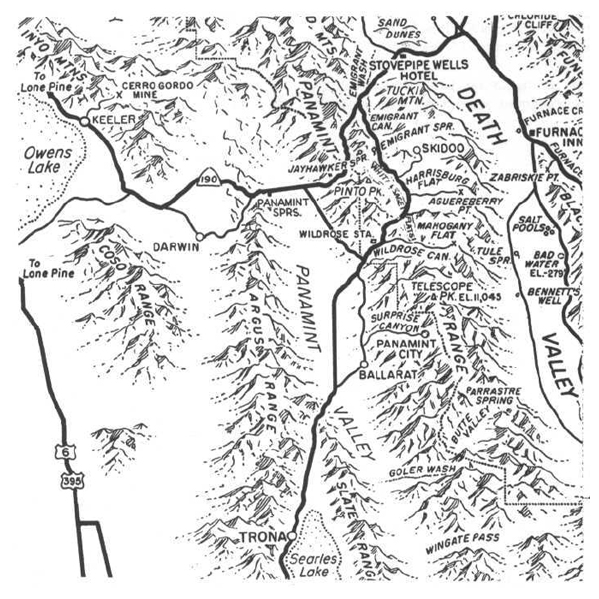

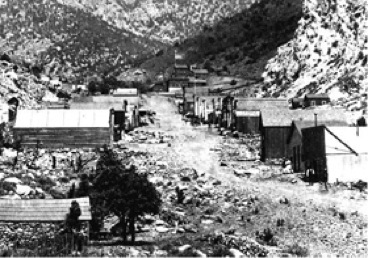

TODAY’S TRAVELER to Panamint sees a crazy quilt of bare foundations and ramshackle walls. He marvels, too, at the old brick mill which for almost 100 years has challenged decay and oblivion. But it is not what he sees that affects the traveler; it’s what he feels. As he stands on the road looking up Surprise Canyon which nestles unpretentiously on the Western slope of the Panamint Range, about 10 miles south of Telescope Peak, the years roll back. Breezes echo gruff, untutored voices, and there is a raucous clang as the 20-stamp mill’s witchery produces precious silver ingots for shipment to “Frisco,” fabled financial capitol of the 70s. The lizard on the big granite boulder is unimpressed that a bearded miner’s pick lay on this same rock many years ago. And now, one looks vainly on the old dirt road for tracks of heavily-loaded desert burros. They’re gone just like the silver city herself.

The story of Panamint probably began in 1859 with the discovery of the Comstock lode. On this date a silver fever began which swept the United States and was especially “fatal” in the Western frontier where curiously every man was a modern day Jason tirelessly searching for his kind of fleece. But after 1859 many frontier men thought of just one thing—to trek the unknown for silver.

William T. Henderson was such a man. Spurred on by the silver news emanating daily from the Comstock, and from legends of the enormously rich lost Gunsight mine, the bearded prospector coaxed his burro across colorful Death Valley. With him were S. P. George and Indian George. S. P. George was weaned on the old gunsight lore. Indian George had long since discarded the ways of the red man and made the hopes of the white man his own.

These three dreamers in I860 skirted the flaming cliffs on the west side of Panamint Mountain. While Henderson found nothing to satisfy his thirst for silver, there was something about the ancient granite and metamorphic rocks of Panamint escarpment that promised wealth untold. So, he returned. This time with a legendary adventurer named William Alvord, a sourdough named Jackson, and the ever faithful Indian George. Again Henderson’s dreams of wealth were stymied. He left Panamint never to return. Alvord, his partner, was more unfortunate still. In the upper reaches of Surprise Canyon he was bushwacked by Jackson and left for vultures. All these anxious probings for silver into the desolate sunscorched Panamints were futile. Silver wasn’t discovered until late in 1872 when two of the most colorful champions of the silver west, R. E. Jacobs and Bob Stewart, wandered up Surprise Canyon and found a huge fragment of rich silver ore.

The great migration to the silver diggings began. Crude buildings sprang up like mushrooms after a spring rain. The most useful Panamint edifice was, of course, the Surprise Valley Mining and Water Company’s 20-stamp mill. It was finished in a matter of weeks while miners with huge stacks of ore chaffed at the bit. Good mechanics, carpenters, and millwrights got top wages of $6 per day. Most popular, of course, were the saloons and Panamint in those days had some fine ones. Like San Francisco, Panamint had its own Palace Hotel. Its barroom was built by skilled Panamint craftsmen and had a beautiful black walnut top. On the side walls were handsome pictures of voluptuous females in varying states of dishabille. But Dave Neagle, the owner of this splendid saloon, was especially proud of his magnificent mirror. It was 8 x 6 feet with double lamps on each side.

Fred Yager early determined that his “Dexter” saloon was going to surpass Neagle’s. Fred especially wanted the finest mirror in town. So, he sent to San Diego for a beauty. The mirror installed was to be a 7 x 12 foot sparkler. Tragedy struck, however, when an inebriated miner fell on the shimmering reflector just as it was being positioned against the wall. Sheltered in the confines of his Palace, Dave must have smiled at his rival’s sore plight—perhaps murmuring encouragingly that breaking a mirror leads to seven years bad luck.

There were two outstanding architectural omissions in Panamint. There was no jail—criminals had to be taken to Independence for incarceration. Further, though it was sorely needed, Panamint never had a hospital. On several occasions Panamint News editors Carr and later Harris cried out in their columns for a community hospital. Interestingly enough, the two crusading editors were mute concerning the lack of a jail.

Although it was not bruited about as such, the building owned and tastefully decorated by Martha Camp, played a significant role in the development of the new town. In Martha’s care was a bevy of attractive, if overly painted, young ladies whose lives were dedicated to two things: to make money and keep miners content.

It cannot be doubted, however, that Panamint prosperity was due to its mines. The two richest were suitably entitled Jacobs Wonder and Stewarts Wonder. Assays of these two mines showed ore values ranging from $100 to $4,000 per ton, the average being about $400. Stewart, a well known Nevada senator, later joined with another Nevada senator, J. P. Jones, to form Surprise Valley’s biggest mining combine, The Surprise Valley Company. Stewart and Jones had other local interests. They owned the Surprise Valley Water Company and a toll road procured from grizzly Sam Tait which trailed up Surprise Canyon. Charges for ascending this road were quite nominal: $2.00 for a wagon, 4 bits for a horseman, and 2 bits for a miner and burro.

The two editors of the Panamint News, at first Carr and later Harris, were rhapsodic in their faith in Panamint’s ultimate prosperity. Late in 1874 the front page of the news throbbed with excitement. “There is reason to believe, the News stated, that a busy population of from three to four thousand souls will be in Panamint in less than a year,” and later, “When we begin to send out our bullion it will be in such abundance as will cause the outside world to wonder if our mountains are not made of silver.” Harris’ beginning enthusiasm must have haunted him later, for his paper of March 2, 1875 modestly informs us that “there were only 600 people at Panamint.”

Despite the fact that the Havilah Miner proclaimed that Panamint City’s silver yield would one day eclipse the Comstock, capital funneled slowly and sporadically into the silver city. Private persons mostly subsidized Panamints mining activities. Senator Jones’ faith in Panamint was shown by hard cash accumulations of partially developed mines. The Senator’s brother caught the silver virus and plunked down $113,000 for a number of claims in the Panamint district. Stock sales never boomed. One wonders if the wildly energetic silver sun of the Comstock lode were not out to eclipse a potential rival. After all, shares in the Con Virginia were flirting a’la Croesus with the San Francisco stock exchange at the $700 mark. More dramatic was E. P. Raine’s method of seeking money for Panamint. He carted 300 lbs. of rich ore across the Mojave to Los Angeles. He staggered into the Clarendon Hotel and dumped the ore on a billiard table. Unfortunately, hotel patrons were more interested in the fact that Raine bought drinks for all than they were in the welfare of Panamint.

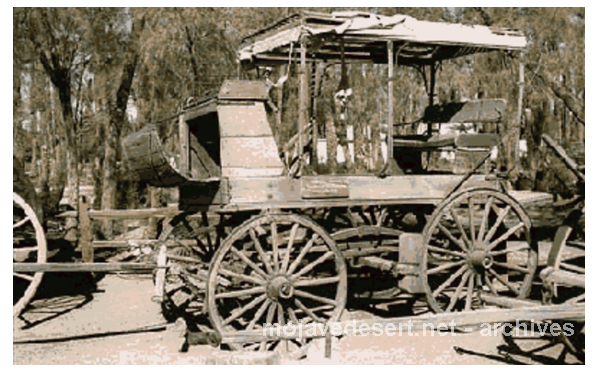

Probably the most popular method of getting freight to Panamint was sending goods via Remi Nadeau’s Cerro Gordo Freighting Company. Remi’s swaggering mule teams made daily trips from San Fernando to the Panamint mines. Remi was ever the epitome of optimism. Although untouched by such 20th Century transportation behemoths as the cross country truck and the jet cargo plane, Remi’s corporate slogan was “all goods marked C. G. F. C. will be forwarded with dispatch.”

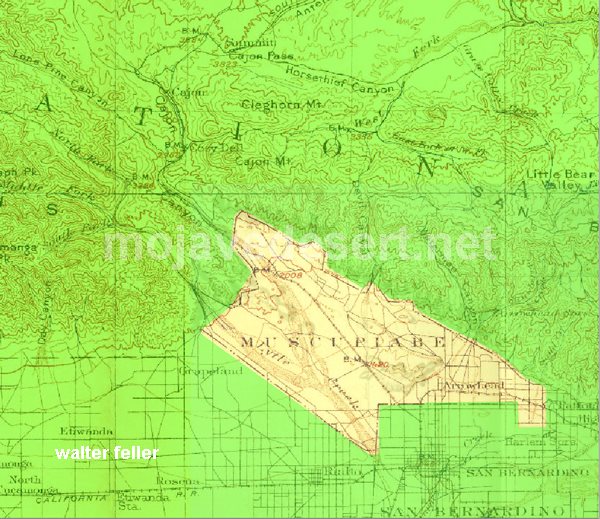

But most characteristic of Panamint transportation in the early days was the solitary miner who arrived on foot followed by a heavily-laden burro. Within his hair-matted bosom slumbered the lion’s share of the vigor and courage of frontier America. Courage, however, wasn’t always the answer on the torrid road to Panamint. Bleached bones of unlucky prospectors sparkled all too frequently in the Mojave sun. When Panamint hearts were at their lightest and silver ore seemed to stretch like a ribbon of wealth to the center of the earth, the people of Panamint, spear headed by their grey-haired champion, Senator Jones, attempted to build a railroad from Shoo Fly (Santa Monica) to Independence. This railroad was to make Panamint the silver empire of the world. Already England was being heralded as an inexhaustible market for Panamint silver. Unfortunately, however, the railroad was to remain a dream railroad. The project clashed with the wishes of the great Southern Pacific quadrumvirate of Stanford, Crocker, Hopkins, and Huntington. The proposed Shoo Fly to Independence railroad won some initial battles—Senator Jones’ Chinese laborers soundly trounced a corps of General Huntington’s forces in the Cajon Pass, but the good Senator lost the decisive battle for his beloved railroad in the hallowed halls of Congress. The Southern Pacific, sans Winchester, had a clear blueprint for winning the West.

Recreation for Panamint’s thrifty merchants and boisterous sourdoughs centered, of course, in the city’s saloons. Whiskey was excellent and surly Jim Bruce dealt in a neat hand of faro. Whether tired miners came into Dave Neagle’s to ogle at pictures of nude ladies, to have a few drinks, or to chat with lovely, but garishly painted young ladies, all present usually had a good

time. Rarely was there serious gun play. Once a Chinese window washer served as target for the six gun of a frolicsome and intoxicated miner, but usually life in a Panamint bar did little to disturb the city’s reputation as an “orderly community.” In their more gentle moments, some men attended the Panamint Masonic Lodge.

For the respectable female, recreational possibilities were severely limited. Legendary is the dance that Miss Delia Donoghue, proprietress of the Wyoming Restaurant, threw in honor of George Washington, the father of her country. To a four piece combo led by learned Professor Martin and paced by the twangs of a soused harpist, doughty men danced with 16 lovely ladies, almost the entire female population of the city.

Panamint certainly wasn’t as wicked as Tombstone, but it had its share of crime. Crime in this petulant silver metropolis ranged from writing threatening letters and petty thievery to infamous murder. The anonymous letters were sent to editor Harris. They criticized his reporting of the murder of Ed Barstow, night watchman for the Panamint News building, by gun fighter and chief undertaker Jim Bruce. This murder took place in Martha Camp’s pleasure house on Maiden Lane. Ed learned that his pal Jim was making time with Sophie Glennon who, demimonde damsel or not, was his girl. He burst into the bedroom firing his six gun blindly. Jim, drawing from his wide experience in such emergencies, sighted his target carefully and pumped two bullets into his erstwhile friend. A sentimental wrapping was given the whole affair when on his death bed Barstow confessed that he was drunk at the time and that his friend was guiltless. More sentiment was piled on when editor Harris used the crime as an excuse for moralizing on the dangers of drink.

A woman figured in one Panamint murder. Sleek Ramon Montenegro resented the words Philip de Rouche used to his comely escort. Montenegro, as lithe as a rattlesnake and with all its speed, knocked down the offender. For revenge, de Rouche later used the butt of his gun to play tattoo on Montenegro’s face. However, the handsome Latin won out in the end. Panamint sreets were a sea of flame for one moment as Montenegro’s gun flashed and killed the Frenchman. Taken to Independence for trial by Deputy Sheriff Ball, Montenegro was tried by a Grand Jury and, although pleading guilty, was acquitted.

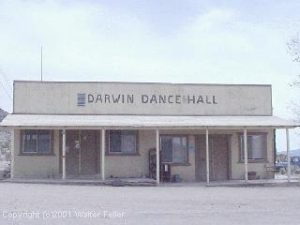

Panamint’s most celebrated crime would probably never have been committed if Panamint were a stable community and due process of law an accepted way of righting wrongs in the silver city. A. Ashim was a respected member of the Panamint community. He belonged to the local Masonic Lodge and ran the town’s largest general merchandising business. But like most town males, Ashim had a six gun and had experience using it. So, when Nick Perasich ran off to Darwin leaving behind an unpaid bill of $47.50 at his store, Ashim walked into a Darwin restaurant. There Ashim shot Perasich three times, killing him instantly. The vendetta which resulted was not inferior to Mafia revenge killings of our day. Perasich’s brothers, led by the volatile Elias, pressed to kill Ashim. They almost succeeded. Hiding behind cornstalks along the roadside, they intercepted the stage and fired into it. Ashim escaped, but his mother received a powder burn on her nose.

But it was those wily ex-New Yorkers, Small and McDonald, who turned Panamint criminology into something resembling a comic opera. From their infamous castle nestled in Wild Rose Canyon, these disheveled silver “knights” rode their sleek chargers into clandestine rendezvous with those jolting fortresses of the West, Wells-Fargo stagecoaches. Once, the wily knaves hunted for a silver mine—and found one. They had no intention of working it. As soon as they could, they unloaded the mine on Senator Stewart. Money received from the sale of the mine could not have come at a more fortuitous moment for the unholy pair. They had been apprehended by Jim Hume, Wells-Fargo investigator, for robbing the Eureka and Palisades stage. Wells-Fargo forgot to press charges when Small and McDonald turned over to them the money received from the Senator for the sale of the mine.

After their close brush with Wells-Fargo, a legend started by twinkle-eyed Senator Stewart says that the desperados kept their eye on Senator Stewart’s progress with his new mine. Alarmed by the undue concern of the bandits with his property, Stewart devised a clever ruse to foil the waiting thieves. He melted ore from the mine into five silver balls weighing over 400 pounds each. When the bandits thought the time was ripe, they opened their saddle bags and

pounced on the mine. Imagine their amazement at the sight of the five huge balls of silver. Legend adds that Stewart was horribly vilified by the disappointed pair for his unsportsmanlike conduct. In this case, however, legend is not correct. Remi Nadeau tells us in his book on California ghost towns that Stewart’s mill fashioned five massive ingots as a precaution against theft.

The criminal activities of Small and McDonald were destined to end soon after the robbery on Harris and Rhine’s store in the spring of 1876. Briefly, the brigands made nuisances of themselves around Bodie. A dispute over spoils, however, led to a heated dispute which led to gun play. John Small was not quite as fast on the draw as his partner.

Why did Panamint die? People nowadays think that the silver veins were surface-bound and did not extend to any great depth. This reasoning appears quite cogent; after all, the silver city’s star did rise and set in four short years. A contrary viewpoint, however, was expressed by Professor O. Loew who, late in 1875, was quoted as saying: “Never have I seen a country where there was a greater probability of true fissure veins than that of Panamint. In the Wyoming and Hemlock mines large bodies of ore will be encountered.” But even as Loew spoke, decay burdened the wind. Editor Harris left Panamint for Darwin in 1875; Doc Bicknell followed soon after. Before Harris packed his wagon for Darwin he advanced his notion why Panamint died—the lack of road and rail transportation. Harris genuinely felt that a railroad could have saved the city.

There was another reason why Panamint became an untimely ghost town. Two hard-bitten prospectors, Baldwin and Wilson, discovered two rich mines in the nearby Coso mountains. The two miners told the people of Panamint that they had the two richest mines in the world. Panamint accepted their words and their enthusiasm as gospel. Immediately a great exodus of wagons trailed down Surprise Canyon headed for the promising capital of the Cosos, Darwin. Unquestionably the discovery of these silver mines in the Cosos provided the coup de grace for the already stricken city as Coso mines were “argentiferous” and did not require milling.

The deluge that swept down Surprise Canyon in 1876 was perhaps the final curtain in this historic drama of the old West. Its rushing waters played around empty shacks and deposited layers of heavy silt on little more than dreams. But there was one person enslaved by the charm of the silver city, Jim Bruce. Long after the mines were closed this formidable faro dealer and gunfighter lived a tranquil if uncertain existence in the city he loved.

Panamint flexed feeble muscles of silver again in 1947. On this date Nathan Elliott, movie press agent, established the American Silver Corporation in a last ditch attempt to wrest silver from long dormant Panamint mines. Elliott spun a sumptuous verbal web that entrapped many of the film Capitol’s finest. Aided by Vice President and Comedian Ben Blue, the silver-tongued promoter succeeded in raising $1,000,000. With this money Panamint mines were deepened. But Elliott’s hopes for a bonanza never materialized. To the wonder and rage of the movie world, the great developer vanished into protective oblivion.

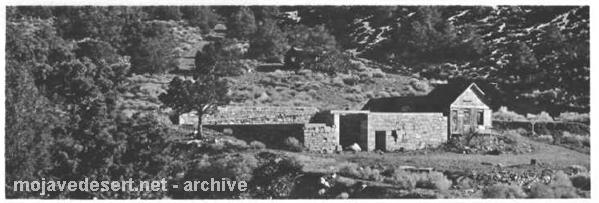

Today Panamint is deserted except for the Thompson sisters who live up Surprise Canyon a few miles north of the old mill. They are old-time residents of the area and their residence, Thompson camp, is a soothing backdrop of green poised against bitter desolation. The Thompson home is encircled by tall trees; a fenced yard secures a well-watered lawn which always has the appearance of being freshly mowed.’ This is due to the wonderful “automatic mower” owned by these ladies, a dusky well-fed burro.

These soft-spoken daughters of the Mojave own a number of mining claims in the area. From time to time they hire miners to sample ores from neighboring hills or to repair rickety scaffolding. Although, the Thompson sisters run a relaxed operation now, their mining activities

would be greatly accelerated by an increase in the price of silver. You can be assured of this not only from what they say, but also from the silvery sparkle that sometimes dances in their eyes.

from:

Tempest in Silver by Stanley Demes – Desert Magazine – February 1967