From: Edward Fitzgerald Beale, a Pioneer in the Path of Empire, 1822-1903

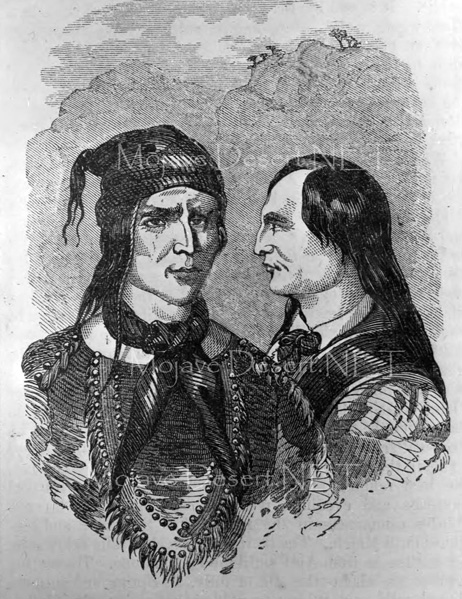

Walkara

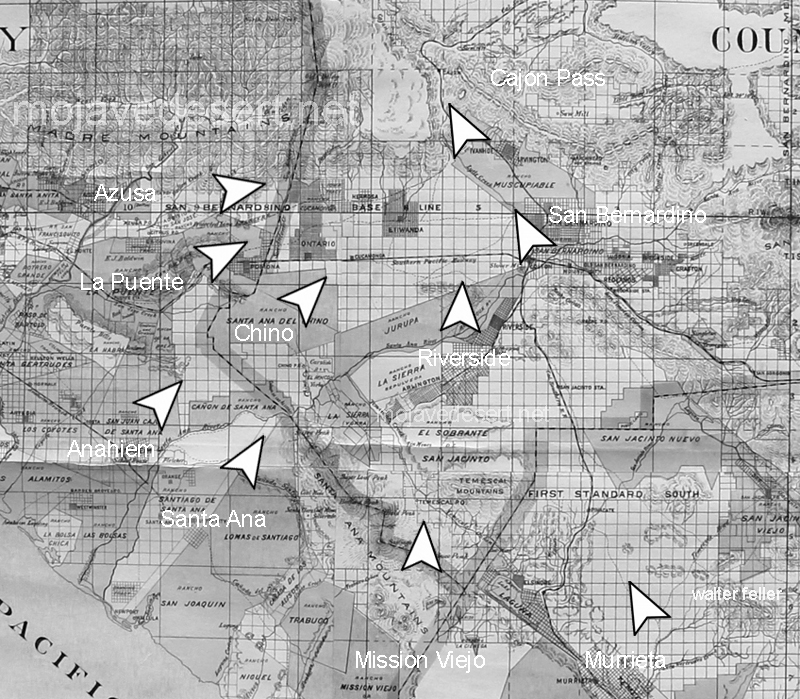

The water of Little Salt Lake is as briny, we were told, like that of Great Salt Lake, and we noticed that its shores were covered with saline incrustations for a mile or more from the water’s edge; but the Mormons stated that the salt was of little value, being impregnated with saleratus and other alkaline matter, which rendered it unfit for use. They obtain their supplies of this article from mines of rock salt in the mountains. The excitement occasioned by the threats of Walkah, the Utah chief, continued to increase during the day we spent at Parowan. Families flocked in from Paragoona, and other small settlements and farms, bringing with them their movables, and their flocks and herds. Parties of mounted men, well-armed, patrolled the country; expresses came in from different quarters, bringing accounts of attacks by the Indians, on small parties and unprotected farms and houses. During our stay, Walkah sent in a polite message to Colonel G. A. Smith, who had military command of the district, and governed it by martial law, telling him that, “The Mormons were d—d fools for abandoning their houses and towns, for he did not intend to molest them there, as it was his intention to confine his depredations to their cattle, and that he advised them to return and mind their crops, for, if they neglected them, they would starve, and be obliged to leave the country, which was not what he desired, for then there would be no cattle for him to take.” He ended by declaring war for four years. This message did not tend to allay the fears of the Mormons, who, in this district, were mostly foreigners, and stood in great awe of Indians.

The Utah chieftain who occasioned all this panic and excitement is a man of great subtlety and indomitable energy. He is not a Utah by birth but has acquired such an extraordinary ascendency over that tribe by his daring exploits, that all the restless spirits and ambitious young warriors in it have joined his standard. Having an unlimited supply of fine horses, and being inured to every fatigue and privation, he keeps the territories of New Mexico and Utah, the provinces of Chihuahua and Sonora, and the southern portion of California in constant alarm. His movements are so rapid, and his plans so skillfully and so secretly laid, that he has never once failed in any enterprise and has scarcely disappeared from one district before he is heard of in another. He frequently divides his men into two or more bands, which making their appearance at different points at the same time, each headed, it is given out, by the dreaded Walkah in person, has given him, with the ignorant Mexicans, the attribute of ubiquity. The principal object of his forays is to drive off horses and cattle, but more particularly the first, and among the Utahs we noticed horses with brands familiar to us in New Mexico and California.

This chief had a brother as valiant and crafty as himself to whom he was greatly attached. Both speaking Spanish and broken English they were enabled to maintain intercourse with the whites without the aid of an interpreter. This brother the Mormons thought they had killed, for, having repelled a night attack on a mill, which was led by him, on the next morning they found a rifle and a hatchet which they recognized as his, and also traces of blood and tracks of men apparently carrying a heavy body. Although rejoicing at the death of one of their most implacable enemies, the Mormons dreaded the wrath of the great chieftain, which they felt would not be appeased until he had avenged his brother’s blood in their own. The Mormons were surprised at our having passed in safety through Walkah’s territory, and they did not know to what they were to attribute their escape from destruction. They told us that the cattle tracks which we had seen a few days previously were those of a portion of a large drove lifted by Walkah, and that the mounted men we had noticed in the mountains in the evening of August 1st were scouts sent out by him to watch our movements. They endeavored to dissuade us from prosecuting our journey, for they stated that it was unsafe to travel even between their towns without an escort of from twenty-five to thirty men.

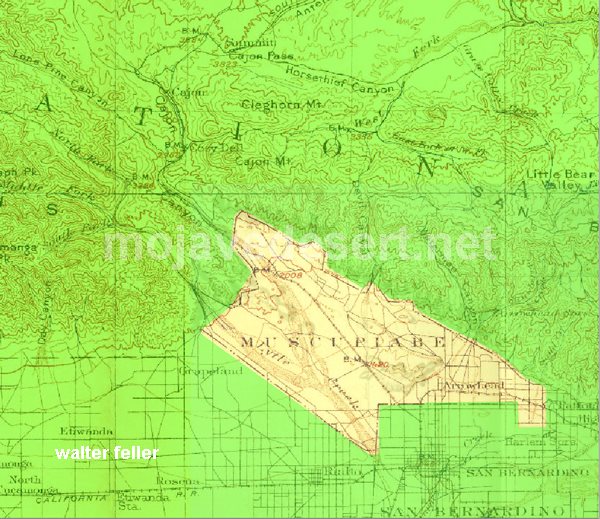

He has adopted the name of Walker (corrupted to Walkah) on account of the close intimacy and friendship which in former days united him to Joe Walker, an old mountaineer, and the same who discovered Walker’s Pass in the Sierra Nevada.

The Mormons had published a reward of fifteen thousand dollars for Walkah’s head, but it was a serious question among them who should “bell the cat.”