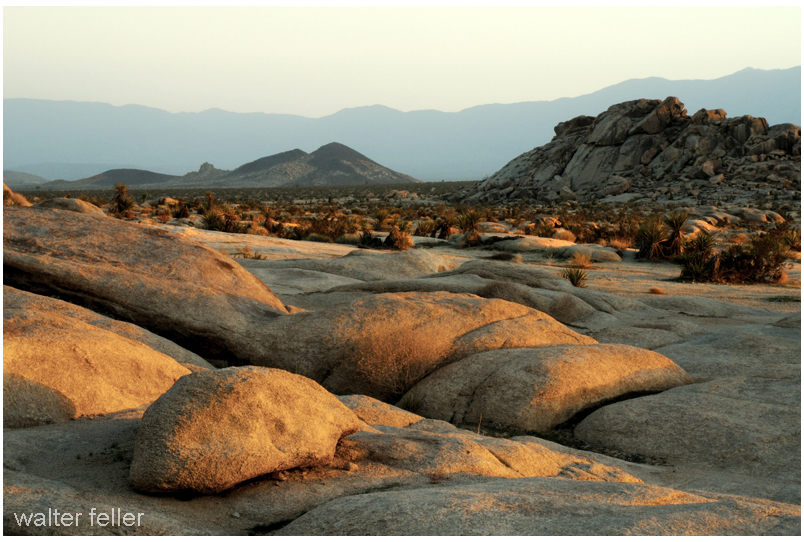

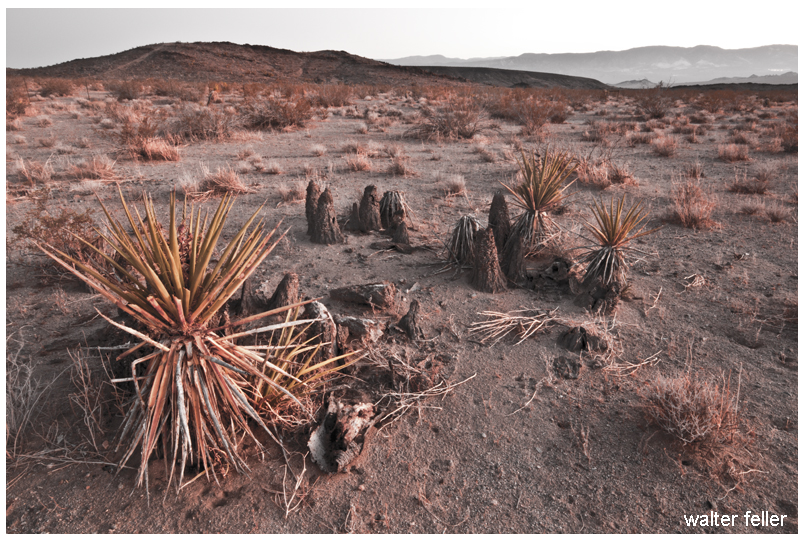

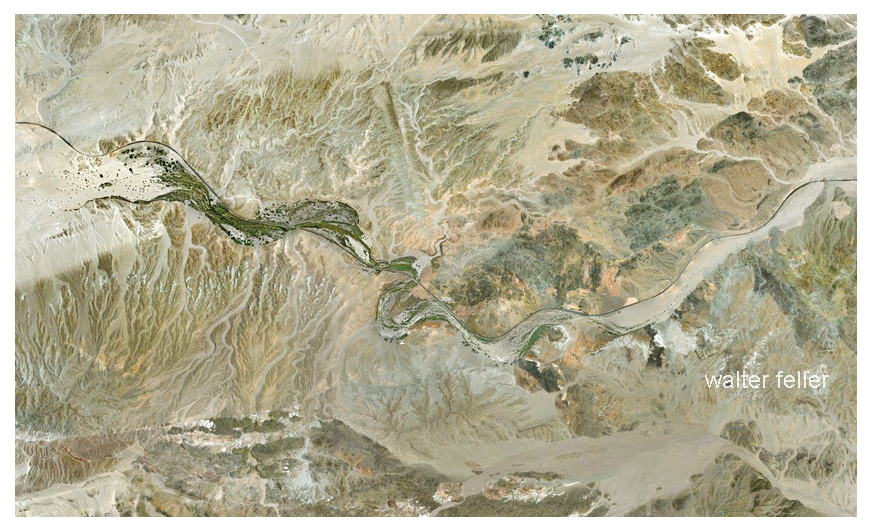

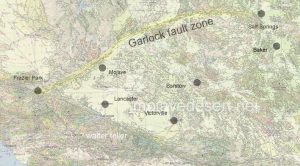

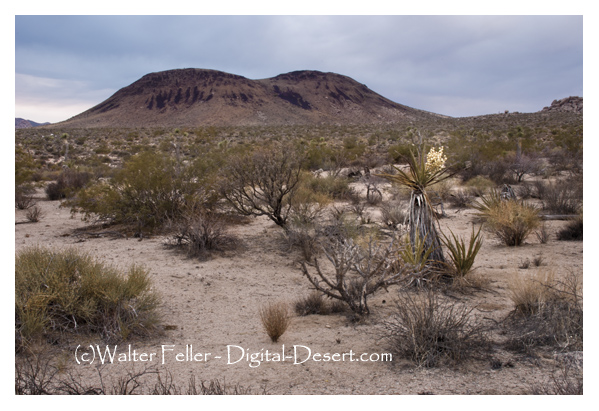

Introduction: The Desert of Illusions Dawn breaks over the Mojave Desert with a hushed reverence. The air is cool and clear, and distant mountains seem deceptively close in the sharp light of early morning. Shimmering heat waves appear on the horizon as the sun climbs, hinting at water that is not there. This land of illusions plays tricks on the eyes and ears. A lone traveler here sinks into the silence and wide-open space, and soon, the mind starts picking up signals most folks usually miss. Shadows at the edge of vision start to move. The senses sharpen. Moreover, sometimes, the line between what is real and imagined blurs.

The Vast Silence and Heightened Senses

One of the Mojave’s most striking features is its deep silence. Away from towns or traffic, the desert can be nearly soundless. In that stillness, the ears strain to find and often invent input. People in extreme quiet sometimes report hearing phantom sounds: faint music, whispers, or even voices. The Mojave is not a sealed room, but the open expanse and quiet air have a similar effect. Cut off from the usual background noise, a lone traveler here sinks into the silence and wide-open space, and soon; the mind starts picking up signals most folks usually miss. Hearing becomes hypersensitive. One may notice their heartbeat or the scrape of a boot echoing off distant rocks. Some desert wanderers describe hearing whispers on the wind—just enough to make some turn their heads.

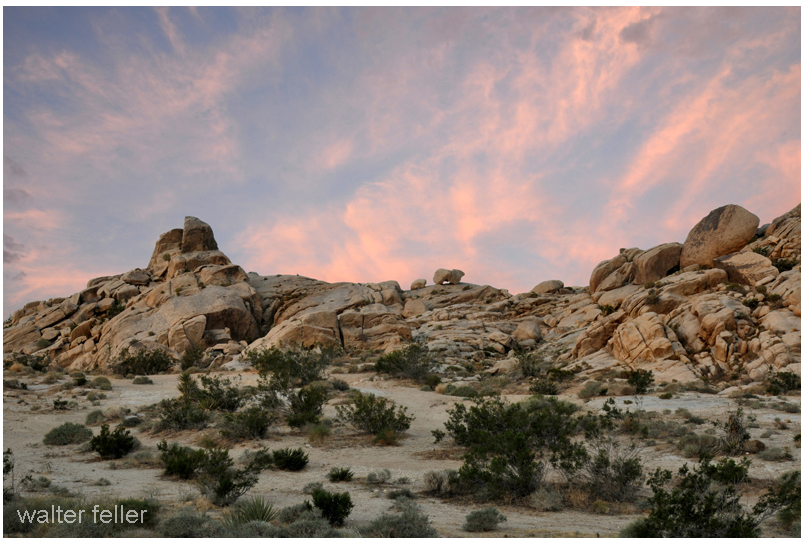

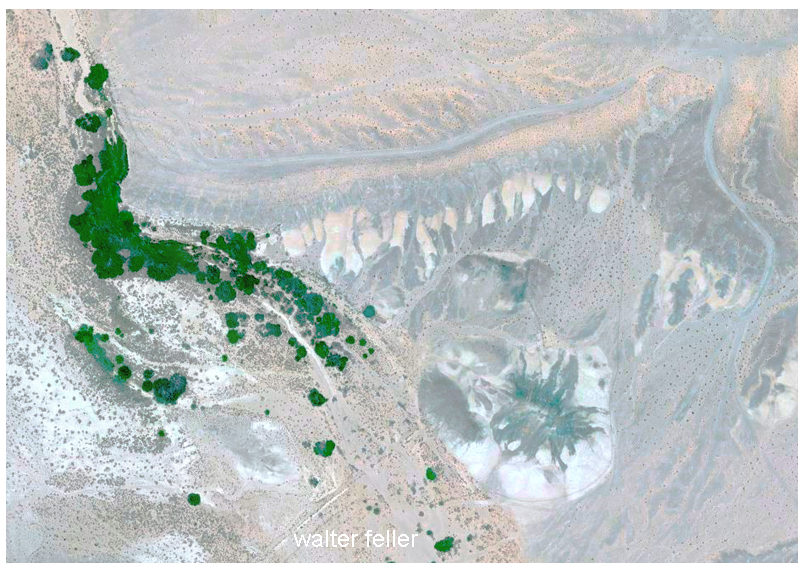

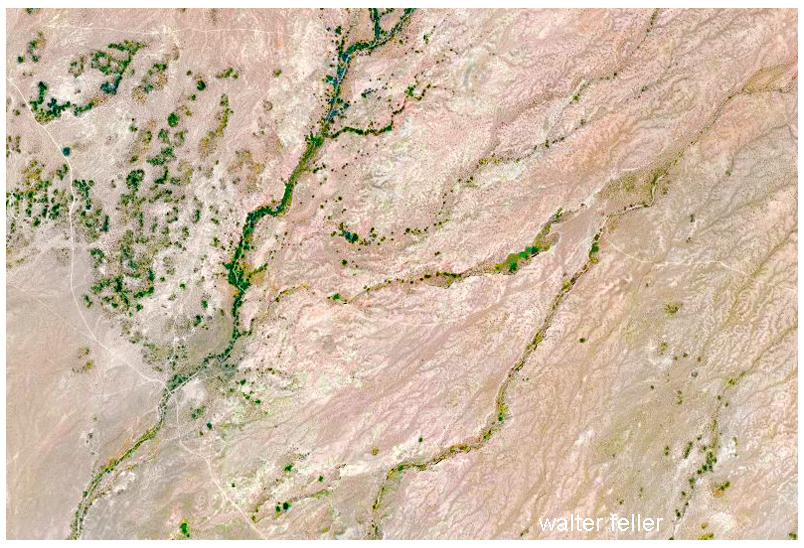

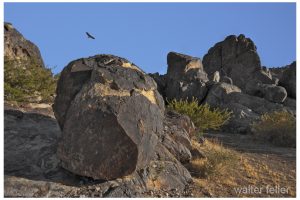

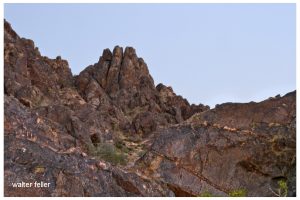

The visual sense sharpens, too. With little to block the view, a person can see for miles. The eye picks up every flicker of movement, and peripheral vision becomes especially active. A lizard’s dart, the shift of a shadow, and even heat ripples can spark a reaction. At night, stargazers in the desert rely on this phenomenon to spot dim stars: looking slightly away from a faint object makes it more visible. However, this same sensitivity can also create illusions. Many travelers have felt watched, only to find a cactus or rock behind them. In the Mojave, the senses amplify every detail; when the brain cannot make sense of something, it fills in the gaps.

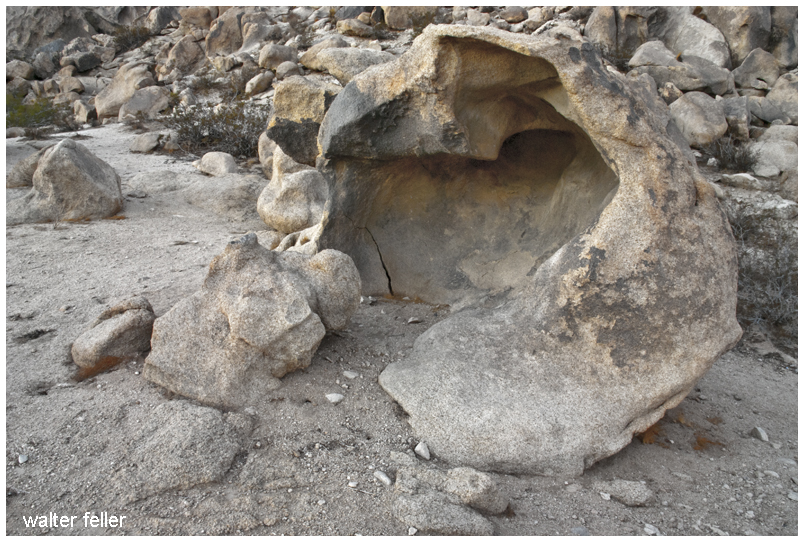

Pareidolia: Faces in the Rocks

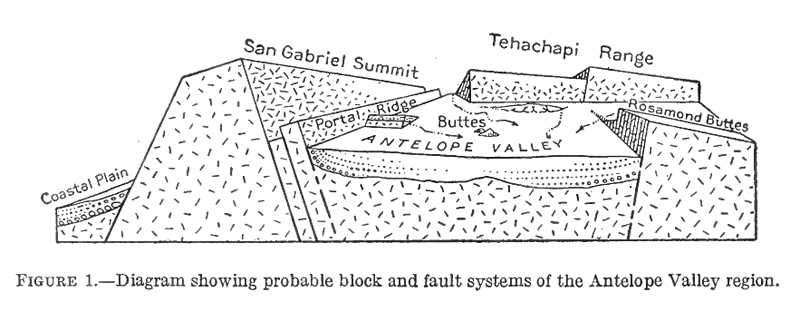

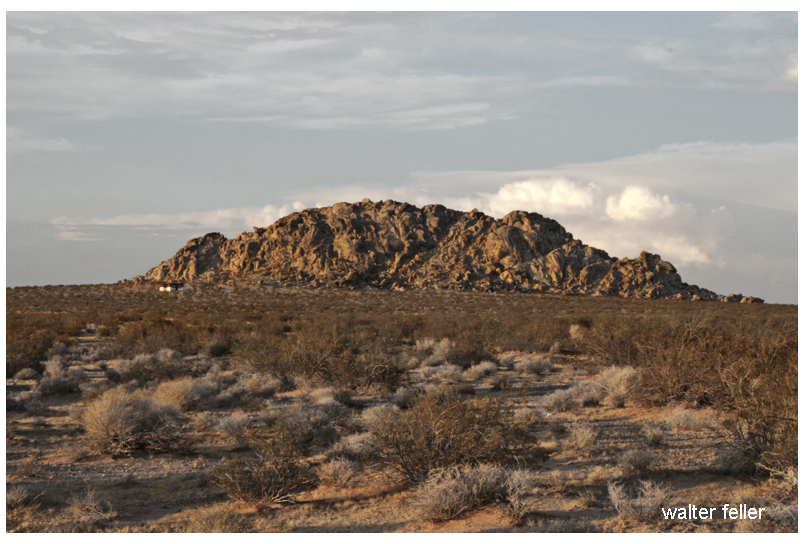

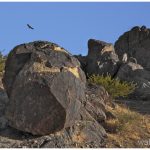

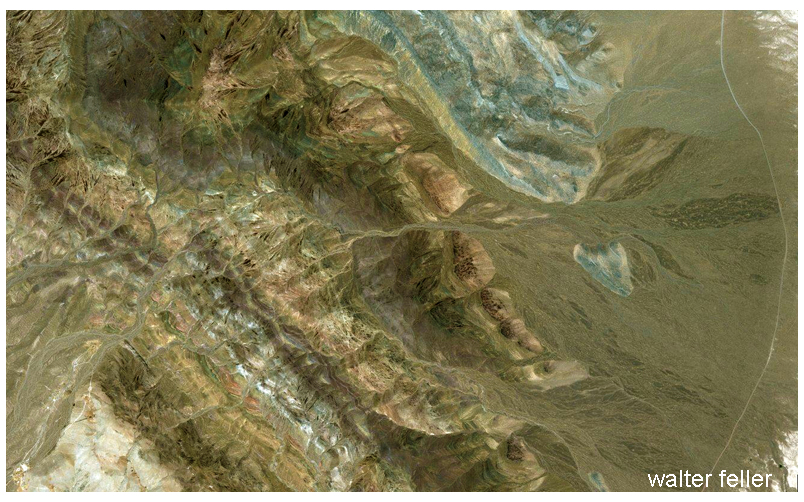

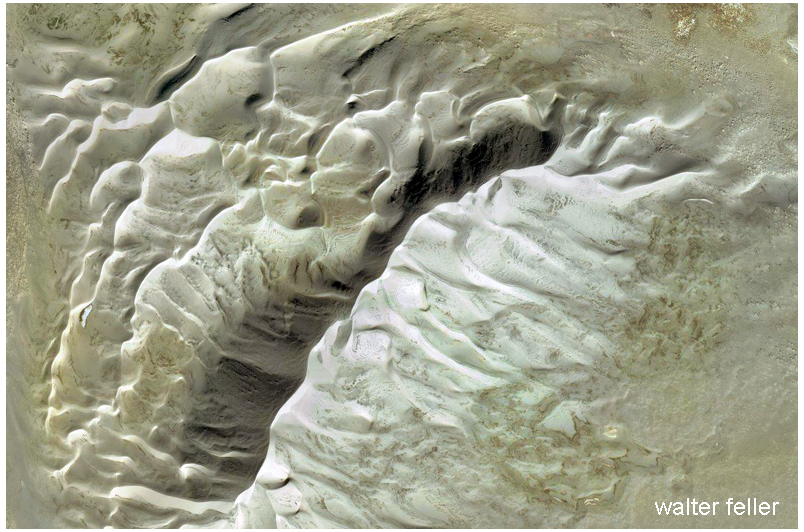

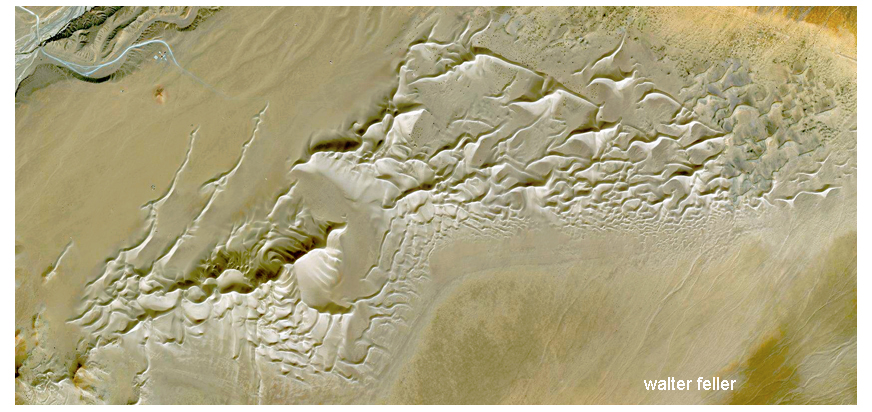

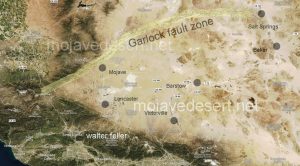

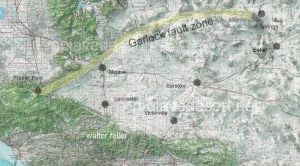

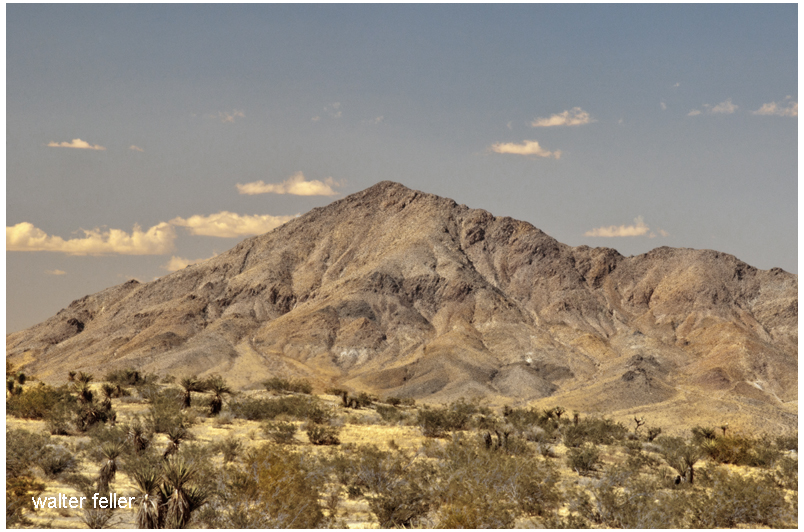

The Mojave is a playground for pareidolia—the tendency to see faces or figures in random patterns. Among the weathered boulders of Joshua Tree or the sculpted cliffs of Red Rock Canyon, it is easy to find rocks that look like skulls, animals, or crouched figures. The mind craves familiarity, and light and shadow give just enough shape to suggest meaning. Visitors often describe seeing people in the rocks or animals in the hills, only to realize it is just how the sun hits the stone. These illusions shift throughout the day. At noon, a rock that’s nothing special might take on a ghostly presence by twilight.

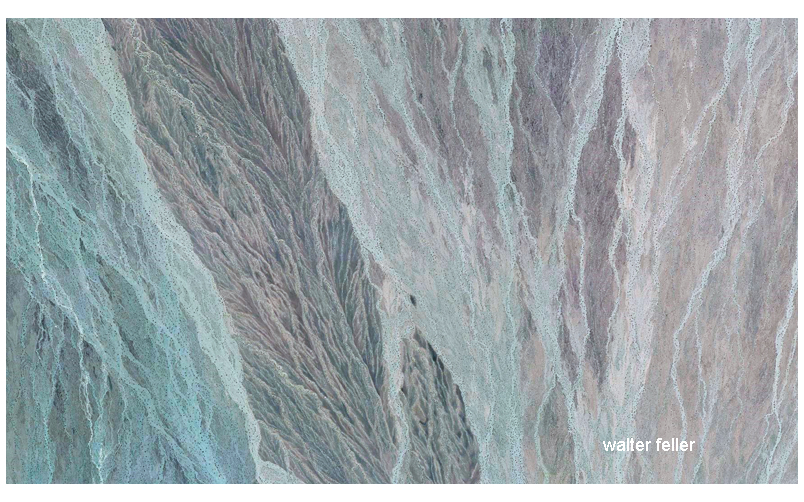

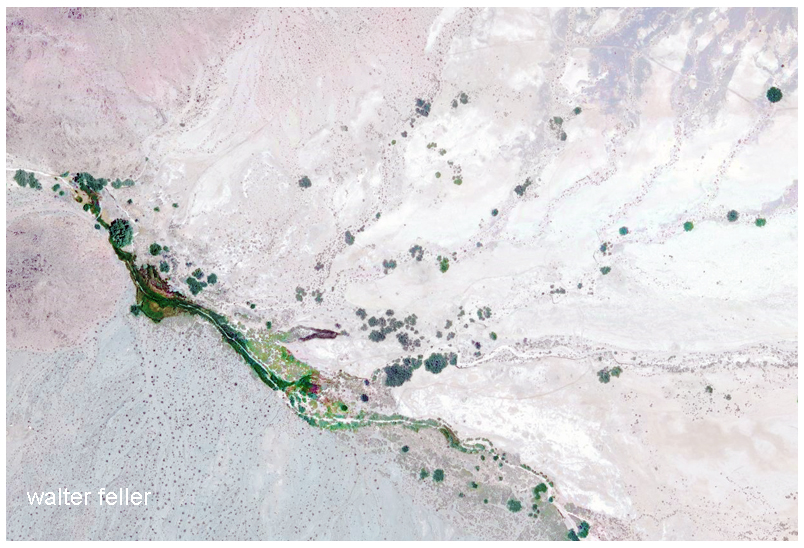

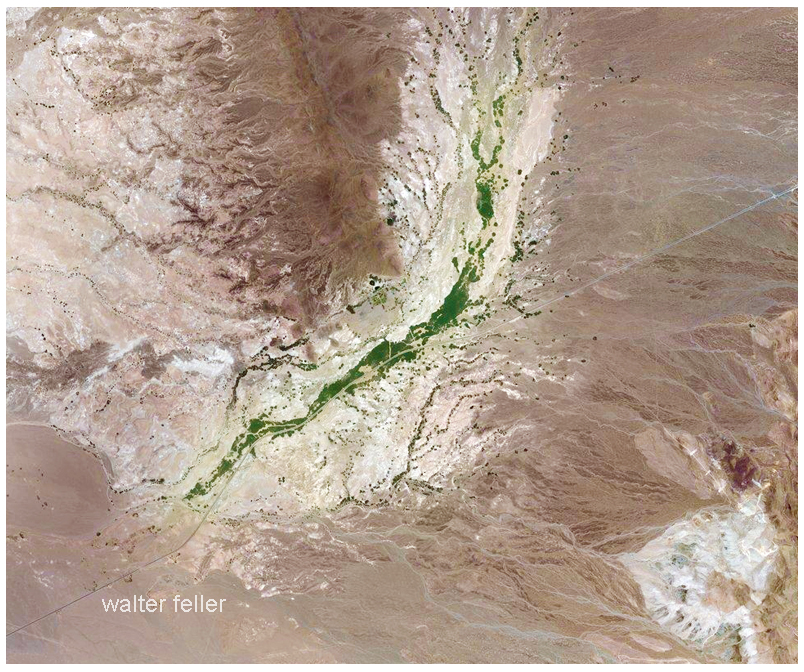

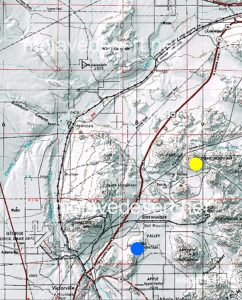

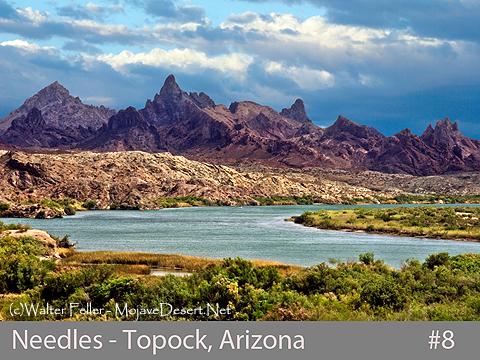

The Mojave’s heat can create true optical illusions even beyond static shapes. Mirages appear across dry lakebeds and salt flats, fooling the eye with phantom water or hovering images. Early travelers chased these shimmering lakes, only to watch them vanish as they approached. The desert air plays with light, creating a shifting, surreal world where the landscape seems to breathe.

Whispers on the Wind: Auditory Hallucinations.

Silence can be just as disorienting as glare. A surreal quiet settles in when the wind is still in the Mojave. People begin to hear things that are not there. The brain, used to constant sound, invents input to fill the void. A whisper might turn out to be wind through Joshua tree branches. Footsteps creeping along could be a kangaroo rat in the brush. The wind can sound like voices when it moves through rock crevices or cactus spines.

In certain corners of the desert, the land itself finds a voice. At Kelso Dunes, when dry sand slips down the slopes just right, it releases a deep, resonant hum—a low, booming note that can hang in the air for minutes. Stumbling across it by chance might give the impression that the ground is singing. The sound is entirely natural yet out of context; it feels otherworldly. It feeds the notion that the Mojave is not just a place but a presence—alive, alert, and willing to speak to those who listen.

Desert Lore and Spiritual Thresholds

Across cultures, deserts are seen as places of vision and revelation. In the Bible, prophets went into the wilderness to confront themselves and hear the divine. Among the Mojave and Chemehuevi people, the desert is not empty but full of spirit. Every mountain and river has a voice. Sitting alone in silence is a way to hear it.

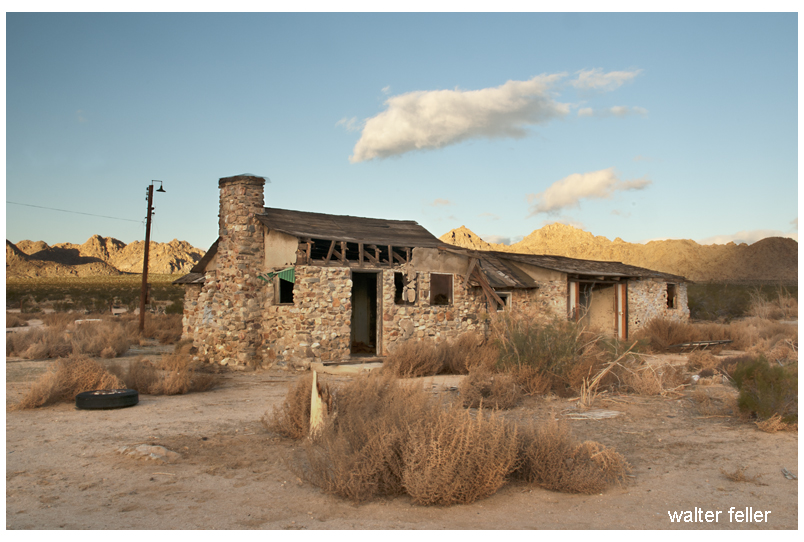

Modern wanderers sometimes have similar experiences. A desert vision might not come with trumpets or lightning but with subtle signs: a shape in a rock, a whisper of wind that feels like a message, or a sudden connection to something beyond oneself. Artists, mystics, and solo hikers often describe the Mojave as a threshold where imagination and reality touch.

Startled or Spellbound: Reactions to the Unseen

These experiences rattle some people. A shadow seen at dusk, a whisper heard at midnight, or a rock that looks too much like a figure can spark real fear. The Mojave has sent many travelers packing, spooked by the sense that something is watching.

Others embrace it. They return again and again, drawn by the mystery. For them, the strange sights and sounds are not threats but invitations to feel small, listen, and see. In this way, the Mojave becomes not just a place but a mirror. What appears in the silence may reveal more about the observer than the land itself.

Conclusion: Embracing the Mirage

In the Mojave, the line between real and imagined begins to blur. The desert does not deceive—it sharpens the senses, asking for attention. A shadow might be only a rock or open a door in the mind. A sound might be wind, or it might be the desert speaking.

Some leave shaken, others changed. One way or another, the Mojave does not simply reveal itself—it reflects what the traveler carries into the silence.