A chapter from Senator Harry Reid’s book

“Searchlight: The Camp That Didn’t Fail”

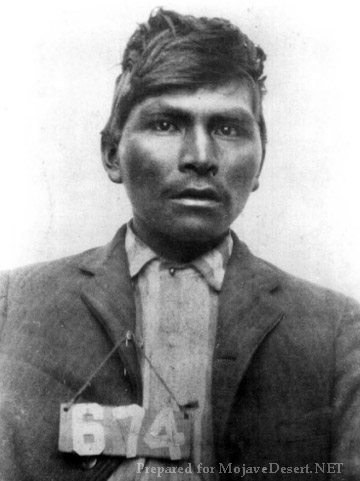

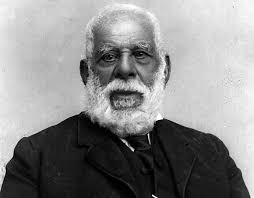

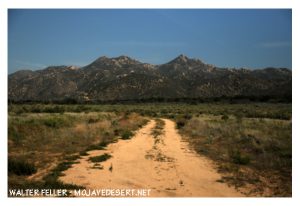

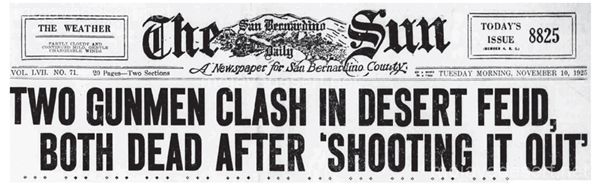

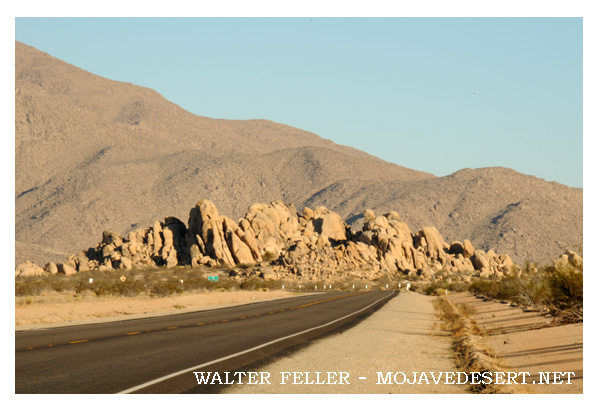

On February 21, 1940, the banner headline in the Las Vegas Review-Journal— BODY OF INDIAN FOUND— recalled for many in the town memories of the first murder the dead Indian had committed, thirty years earlier at Timber Mountain, just a few miles from Searchlight in the McCullough Range.

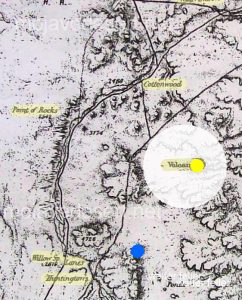

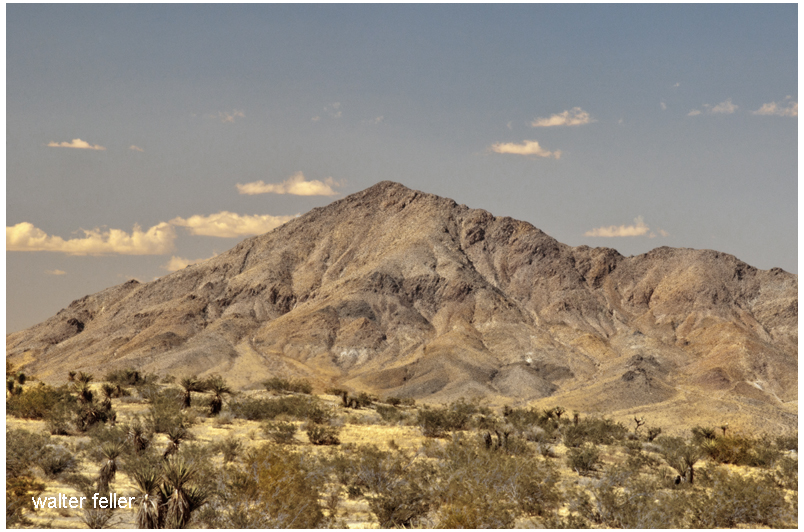

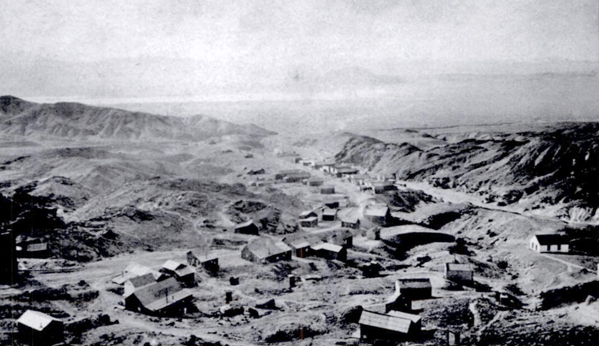

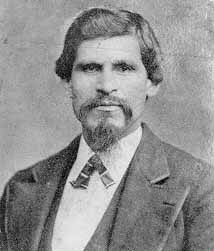

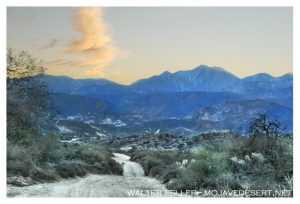

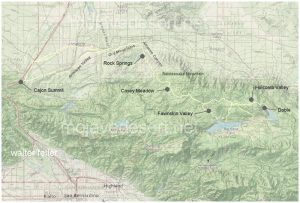

On a cool fall day in October 1910, Harriett and John Reid were on their way, via horse-drawn wagon, to work at their mine—she manned the horse-operated hoist, and he mined the ore. They could see an Indian approaching them, carrying a .30-.30 Winchester rifle and traveling at a very fast pace. The Reids stopped, as did the Indian, whom they recognized as Queho, an acquaintance who worked at various menial jobs throughout the Searchlight area. They exchanged greetings and after a brief visit went their separate ways. Later, the Reids and everyone else in the area learned that Queho had been hurrying down from Timber Mountain, where he had been cutting wood for J.W. Woodworth, a timber and firewood contractor. Woodworth had refused to pay Queho, who then flew into a rage and beat the man to death with one of the timbers he had cut. This murder was the beginning of an odyssey that took thirty years to play out.

Queho soon struck again, this time near the river in Eldorado Canyon, at the Gold Bug Mine, which was partially owned by Frank Rockefeller, brother of John D. Rockefeller. A short time afterward, Queho admitted to Canyon Charlie, an Indian elder almost a hundred years old, that he had killed the mine’s night watchman, his former employer. The second murder occurred on the route between the Crescent area, where the woodcutter was killed, and the river.

Local lawmen, who viewed Queho as little more than an ignorant savage, thought that catching him would be child’s play. They couldn’t have been more wrong. The clever Indian stole a horse from a man named Cox and eluded the law.

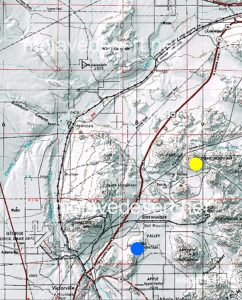

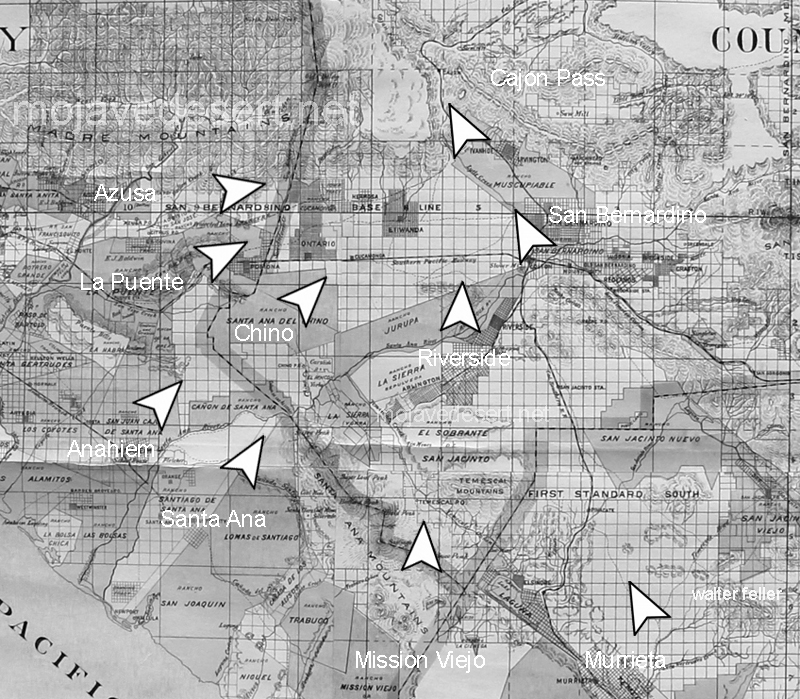

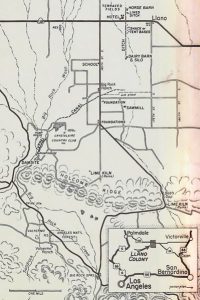

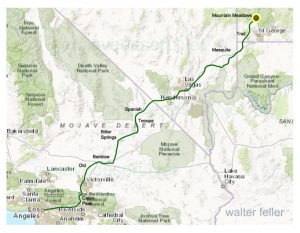

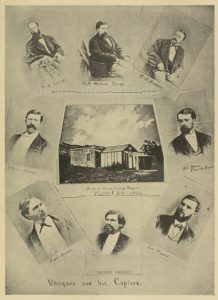

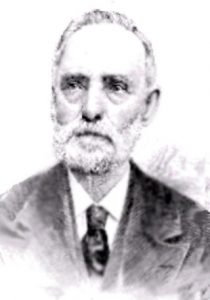

A large manhunt was organized to apprehend the Indian outlaw. It was assumed that Queho would be easy to track, since he dragged one leg as a result of an earlier injury. James Babcock, an operator of the Eldorado mine and a lawyer educated in Washington, D.C., led the search party. He was accompanied by a contingent of Las Vegas lawmen, including Ike Alcock, as well as Indian trackers and an Indian agent named DeCrevecoeur. One of the pursuers was overheard remarking that Queho’s chances of living a long and happy life were very slim. The manhunt extended more than 200 miles, ranging from Crescent to Nipton and even coursing toward Pahranagat Valley, nearly 150 miles to the north. The pursuers gave up the search when supplies ran out and they grew weary. At that point the lawmen began to suspect that maybe this Indian was cunning and smart, not quite the “dumb” savage they had thought.

Queho was subsequently blamed for a number of murders that he did not commit. The first was the murder of James Patterson. The newspaper headline read, MAN KILLED BY QUEHO STILL ALIVE. Patterson hadn’t been killed by the Indian or anyone else—as was evident when he turned up alive and unharmed. But in the course of looking for Patterson, the search party found another man whom Queho had shot.

The press closely followed Queho’s escapades. A reward of $500 was offered for the Indian’s capture, and Nevada’s only member of Congress announced that the federal government should assist in the capture of this madman.

In March 1911 it was reported that two men on the Arizona side of the river, just below Searchlight, watched Queho beat a white man to death on the opposite side. The prospectors were powerless to help, as they had no way to cross the river; they were also unarmed and feared that Queho was armed and would attack them. By this time fear gripped the entire region.

It was believed that the best method for apprehending Queho was to enlist the Piutes in the search, which was the standard operating procedure at the time. Whites regularly abused and harassed the Indians, and if an Indian committed a crime, the white community would force the Indians to produce someone to answer for the crime. To fail in this responsibility meant great distress for the Indians because it led to further harassment by the whites.

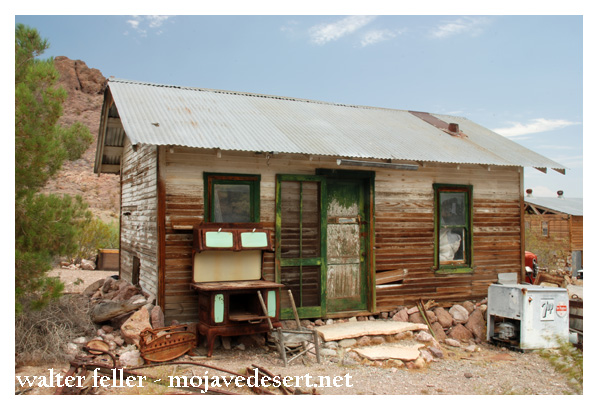

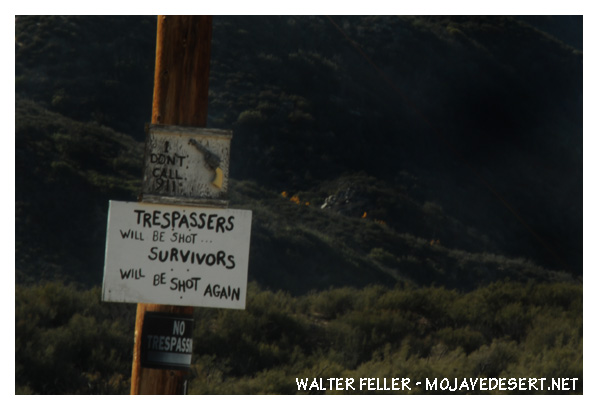

In the hills below Searchlight, about five miles from the river, one of the Du Pont heirs to the chemical fortune of the Eastern United States was encamped. He was an outcast from his famous family. At the urging of voices that only he could hear, he began digging a tunnel through one of the volcanic mountains with a pick and shovel. He started the tunnel in 1896, even before gold was discovered in Searchlight, and eventually extended it nearly 2,000 feet through the solid volcanic rock. Du Pont was always friendly to the Indians who came by his camp and often shared his provisions with them. But shortly after the murders of Woodworth and the Gold Bug watchman, some of Du Pont’s supplies disappeared, and Queho was said to be the culprit. The newspaper editorialized that the federal government owed a responsibility to the people of Searchlight to intercede in this Indian affair. It wrote: “A good Indian is a dead Indian.”

Most still believed Queho would be caught, that with both Indians and whites on his trail victory was assured. The Las Vegas Age newspaper headlined an article with QUEHO THE BAD INDIAN IS IN A BAD FIX. In a subsequent edition the paper said that civilians and bad whiskey had turned Queho into the killer he was. The paper also observed: “It is very probable that Mr. Queho’s days are numbered considering those after him.”

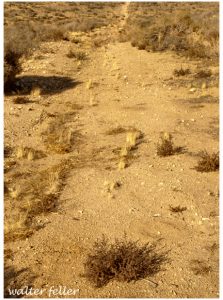

The posse was large and well equipped, as all other hunting and tracking parties had been. At this point it was believed that Queho had come back to the river. Alcock wrote to Constable Colton in Searchlight, informing him that he was on the trail of Queho, as he had recently found fresh tracks at Cow Wells, near Searchlight. Queho was also reported to have been seen in the town itself at least once. The posse came up empty-handed.

In 1912 Fred Pine, while hunting near Timber Mountain, came upon Queho, who was armed with his ever-present Winchester. The men exchanged greetings. Pine asked Queho if he would like one of his sandwiches. Queho accepted, and in return offered, Pine one of his dried rats or chipmunks. Pine finally turned to leave, expecting at any moment to be shot in the back, but nothing happened.

Queho was surely an expert at hunting and fishing. He could eat anything, including tortoises, chuckawallas, burros, horses, mountain sheep, chipmunks, rats and various birds.

The Queho legend began to grow. Several manhunts were organized—all public, all ending in failure. The Searchlight newspaper ceased publication, so news about the comings and goings of the fugitive was no longer so sensationalized. Though some believed he had been killed by other Indians, occasional sightings were reported. There were even rumors that he had a girlfriend around Searchlight named Indian Mary. Others reported having seen him in Searchlight. Murl Emery told people that he had seen Queho several times. Searchlight residents indicated that some contact was maintained with him over the next twenty-five years.

Seven years later, in the winter of 1919, the peace of the countryside was again shattered when Maude Douglas was murdered in her home at the Techatticup Mine in Eldorado Canyon. She heard a noise in the dead of night, walked into the kitchen to investigate, and was felled by a shotgun blast. On the floor was spilled cornmeal that the intruder had been trying to take from the cupboard. The trail from the cabin showed tracks of a man with a noticeable limp, like Queho’s.

Mrs. Douglas was married and had two children of her own, as well as the responsibility for two other small youngsters, Bertha and Leo Kennedy. Leo, who was only four years old at the time of the murder, later said that Maude had been killed by Arvin Douglas, the man of the house. There is no corroborating evidence to support that claim, especially in view of the uniquely patterned tracks at the Douglas cabin. Bertha also said that she felt responsible, because she had awakened Mrs. Douglas for a drink of water and if she had not done that, the woman would not have gone into the kitchen.

The overwhelming weight of the evidence pointed to Queho, as confirmed by a coroner’s inquest that was convened after Maude’s death. The coroner determined that she had been shot at close range and that the tracks from the house fit Queho’s.

The murder of Maude Douglas initiated a new era of Queho hunting. During the chase, the search party found a mountain sheep that Queho had recently slaughtered. They also found two dead miners named Taylor and Hancock, whom he had killed with their own prospector’s pick. The searchers soon learned that Queho traveled at night and holed up during the day. The pursuit ended in futility after three weeks, with the near death of the group’s leader, Frank Wait, from exhaustion.

Wait believed that Queho was hiding in the area where he had killed Woodworth. Knowing that he was being followed, Queho did not want to attract attention with gunshots, so he killed the two miners with their pick, probably to get a replacement for his worn boots. Sheriff Joe Keate described him as being able to starve a coyote to death and still have plenty of strength to continue. He reportedly knew of places in the desert where depressions worn into the rock stored rainwater for up to a year.

Alcock, a man named Alvord, an Indian trader named Baboon, and ten others made up the search party. Among the group were some Indians, and it was discovered that they were signaling Queho by smoke signal, thus allowing the killer to elude his pursuers.

The reward was increased to $3,000. Individuals and groups found evidence of Queho—a cave he had stayed in along the Colorado, remains of a mountain sheep and a burro.

For the next few years, another period of quiet prevailed when no recorded murders were known to have been committed by Queho. Nevertheless, no one felt secure. Prospectors and others tried to travel in pairs, one or the other of them always keeping watch at night. Not until 1935 did the next confirmed sighting of Queho take place. A cowboy named Charles Parker had a mare disappear; a week later the horse was found with part of its carcass cut away, obviously for eating. Upon investigating, the cowboy got more than he had bargained for. He was accosted by a scantily clad Indian with long, stringy hair and was robbed, but escaped unharmed. Searching the same area later, Parker and others found a cave along the river with drying jerky in it. A gunfight ensued and nine shots were fired, with no apparent injury to either of the parties.

As the years passed, Queho was accused of killing as many as twenty-one people. His first murder actually occurred before the Woodworth episode; the victim was his cousin or half brother, an Indian outlaw named Avote. The white community insisted that the Indians

produce someone to pay for Avote’s crimes, and so as a young man, Queho killed his relative at Cottonwood Island on the river below Searchlight. He also likely killed Bismark, a Las Vegas Indian, but that was a tribal killing and would not usually have been pursued in early Las Vegas. There were allegations of other killings but no actual proof.

Queho outsmarted the best that law enforcement had to offer. His pursuers may have come close on several occasions, but he always evaded him. He was an excellent shot and had a reputation of being extremely brutal.

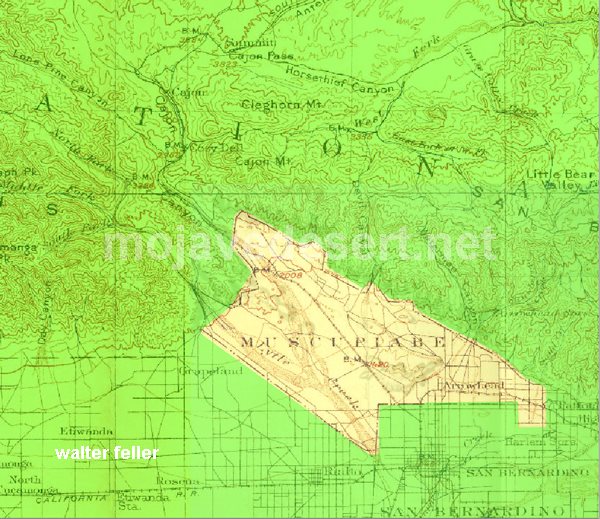

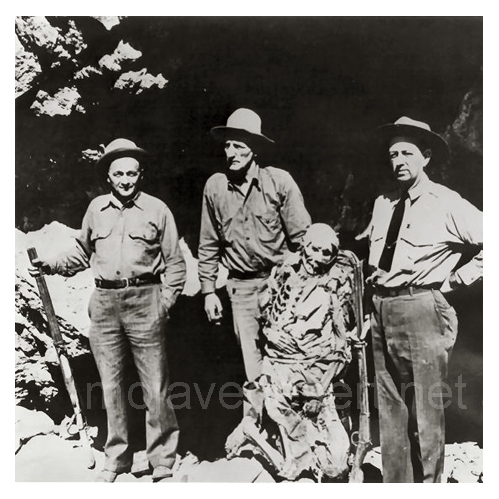

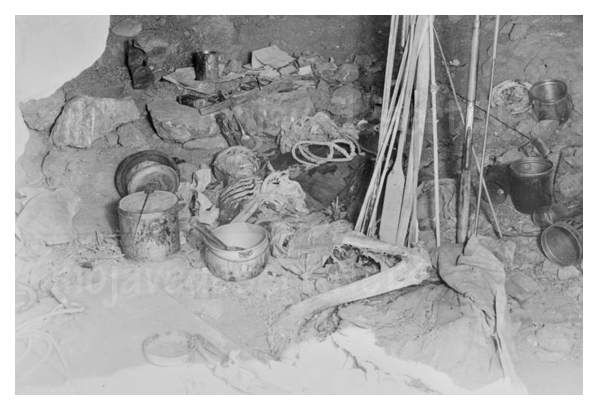

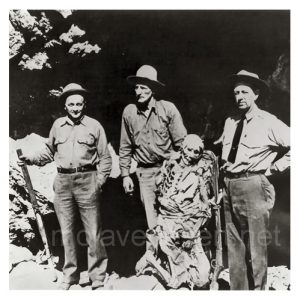

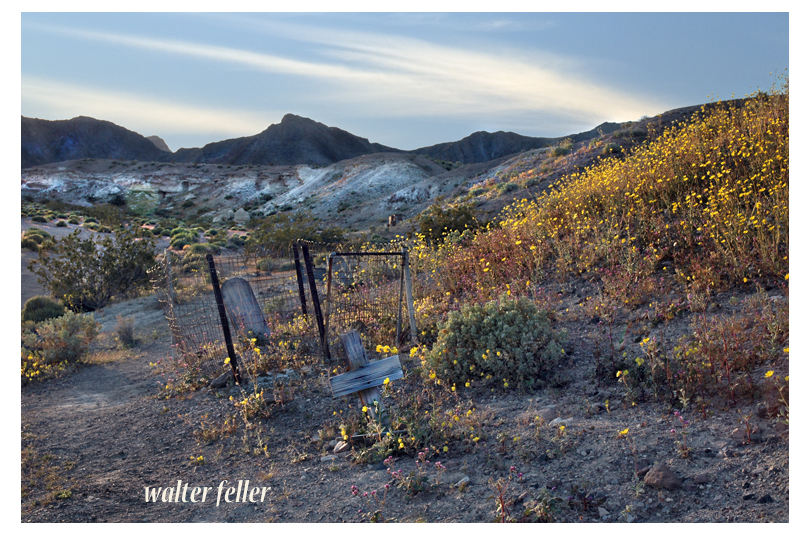

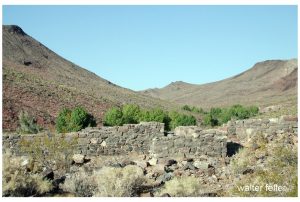

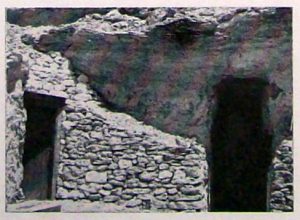

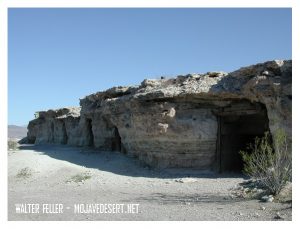

Finally, in February 1940, Queho’s body was found by three prospectors in a cave about ten miles below Boulder Dam and 2,000 feet above the river. They also found fuses and blasting caps from the dam at the site. This cave was one of the best hidden and most impregnable hideaways imaginable. It even had a trip wire hooked to a bell to alert him of intruders. Queho had been dead for at least six months.

Some of his old pursuers, not wanting to acknowledge that they had been outsmarted for thirty years, tried to say he had been dead since 1919. Items in the cave from the construction of Boulder Dam quickly disproved their claim—veneer board, used in concrete moldings at the dam, that Queho used for protection from the elements. And there were fuses, which he used for reloading his bullets and shotgun shells. Also discovered in the cave was the badge of the night watchman killed at the Gold Bug Mine. His loaded Winchester rifle and the shotgun with which he likely killed Maude Douglas were in the cave, as well as a fine bow and twelve steel-tipped arrows (probably for fishing in the river), recently minted coins, and papers from some of his victims.

The large number of eyeglasses in the cave probably indicated that he was afflicted with poor eyesight in his later years. At death he was believed to be about sixty years old. He had died in a position of apparent pain, wearing a canvas hat and pants. One of his legs was wrapped with burlap, which indicated that he may have been snake-bitten. A former acquaintance confirmed the identity of the body by the unusual dental feature of double rows of teeth.

Charley Kenyon, one of the prospectors who discovered Queho’s body, later found other nearby caves that the Indian had used. Queho was also said to have panned a little gold, which he saved in Bull Durham tobacco sacks, then exchanged for food and other supplies. One of the persons who probably had some contact with Queho was the eminent Murl Emery, who always seemed protective of him and also admitted to leaving food for him. Emery was quoted as saying, “Why don’t you let the poor Indian rest?” Emery lived at and operated Nelson’s Landing for many years and was a constant companion of mystery writer Erle Stanley Gardner.

Queho remained controversial even after death. Two political enemies and former law enforcement officers, Gene Ward and Frank Wait, both involved in trying to bring the desperado to justice over the years, fought over his skeleton.

Neither won, as James Cashman and the Elks Lodge intervened to pay the funeral home for the costs of interment. The Elks then displayed Queho’s bones at Helldorado (the premier entertainment event in Las Vegas for more than forty years, beginning in the 1930s) as in a carnival attraction.

The bones were stolen from Helldorado Village and found in Bonanza Wash in Las Vegas; Dick Seneker subsequently acquired them and returned them when James Cashman again offered a reward. The Indian’s remains are now believed to be buried in Cathedral Canyon near Pahrump.

Queho’s name continues to bring forth tales too numerous to confirm. In an oral statement taken in the late 1970s, historian Elbert Edwards of Boulder City gave a rambling account of stories about Queho. Edwards did not rebut the stories of Queho’s murderous binge, attributing a total of seventeen murders to the Indian.

Edwards described one man who was killed with a pick handle before Woodworth was killed at Timber Mountain. He then confirmed the murders of the Gold Bug watchman, Maude Douglas at Nelson, the two St. Thomas miners Hancock and Taylor, and then two unidentified miners. He also described Queho’s murder of a wandering cowboy with his trusty rifle and spoke of five individuals who were killed in a cabin near what is now Boulder Dam—three with a rifle and two with a knife. Edwards’s narrative also related the story of two others, killed in nearby Black Canyon the next day. The authenticity of most of the murders recounted by Edwards is questionable, but they do reveal the legendary status accorded this Indian desperado.

Queho was a killer who outsmarted all who tried to capture him. The story is tragic, not only because of the lives that he took but because even in Searchlight his story illustrates to us how poorly Indians were treated. The first census, in 1900, reported forty-two Indians in Searchlight, obviously in the river area where there was water. They were eventually driven out of Searchlight.

In the summer of 1905 the Searchlight newspaper reported that the Indian village on the outskirts of town had been destroyed by fire. The paper disparagingly remarked: “All bucks and squaws were away.” Indians were granted no respect in Searchlight, and they were harassed and discriminated against in increasingly offensive ways. It is no wonder that Queho’s fellow Indians helped him. Nor is it surprising that he became known among the few Indians of the area as someone who had stood up to the white man.

–

From: Senator Harry Reid’s book, “Searchlight, The Camp That Didn’t Fail,”

University of Nevada Press.

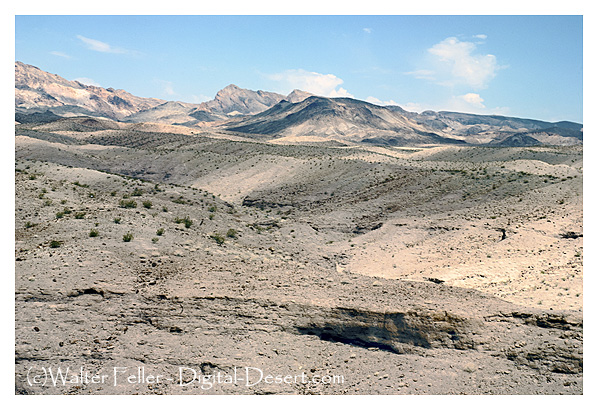

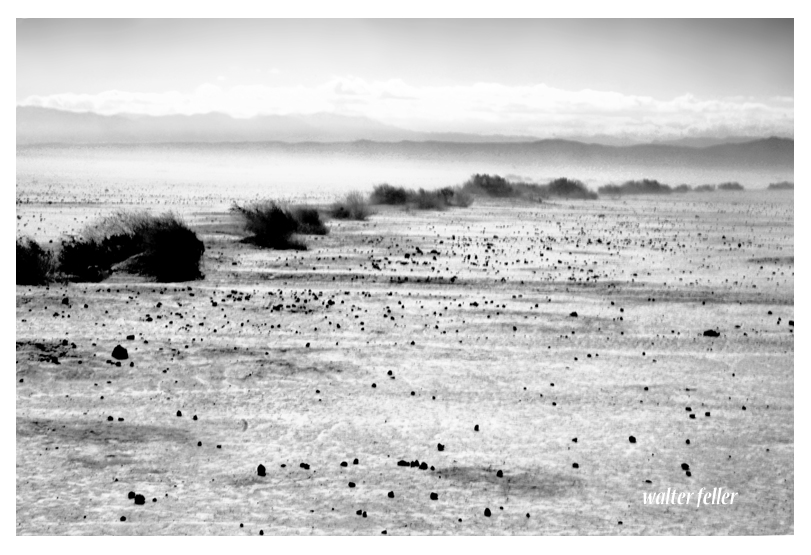

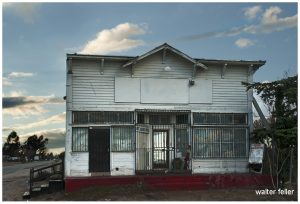

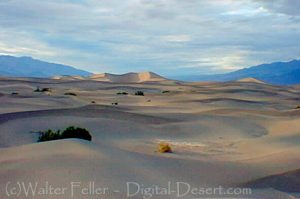

Death Valley was having one of its periodic wind storms when the tourists drove up in front of Inferno store to have their gas tank filled.

Death Valley was having one of its periodic wind storms when the tourists drove up in front of Inferno store to have their gas tank filled.

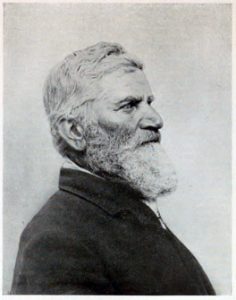

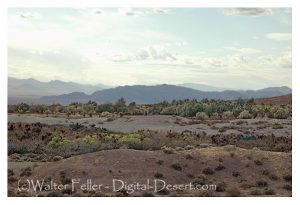

Sandy Walker says you can’t find gold with Fords – have to have burros. Says he’s been out here in the desert 26 years, 6 years hunting gold and 20 years hunting burros. He didn’t find his mine while hunting gold. He found it while hunting his dadburned runaway burros.

Sandy Walker says you can’t find gold with Fords – have to have burros. Says he’s been out here in the desert 26 years, 6 years hunting gold and 20 years hunting burros. He didn’t find his mine while hunting gold. He found it while hunting his dadburned runaway burros.