The Long Trail West

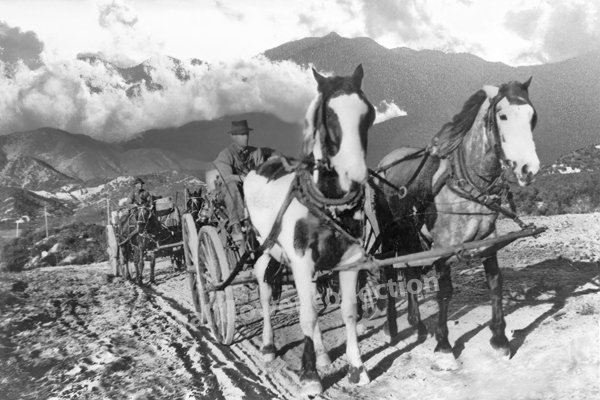

In the final months of 1864, while the nation was still locked in the chaos of the Civil War, a wagon train rolled slowly across the American frontier. Among its passengers were two families whose names—at least in one case—would echo through the pages of Western legend. The Rousseaus were heading west in hopes of a new beginning. Hardened by war and failure, the Earps sought a better future in California. Leading the wagon train was Nicholas Porter Earp, father of Wyatt Earp, and it was here—on the unmarked road between Salt Lake and San Bernardino—that stories of strength, tension, and hardship unfolded, written down by the steady hand of Sarah Jane Rousseau in her trail diary.

Nicholas Earp was, by any account, a man built for difficult times. Born in 1813, he had lived through the War of 1812 as a boy, served in the Black Hawk War, and later took up arms in the Mexican-American War. He had worked as a farmer, a constable, and a jack-of-all-trades—never truly settling, always looking for something better over the subsequent rise. By 1864, Earp was in his early 50s, grizzled and stiff from rough work. He was also deeply set in his ways.

Descriptions of Nicholas during the journey paint him as short-tempered, headstrong, and deeply opinionated. He took command of the wagon train with the same kind of stern authority one might expect from a battlefield officer. There was little room for softness on the trail. Rules were rules. And if they weren’t followed, the consequences were loud, and sometimes threatening. This didn’t sit well with everyone.

While traveling with her husband, Dr. John Rousseau, and their children, Sarah Jane Rousseau kept a diary of the journey. Her writing is a rare window into the human side of westward migration, especially from a woman’s point of view. She recorded weather patterns, daily mileage, and significant encounters. But she also took note of personalities and frictions along the trail, and Nicholas Earp features more than once in that record, which is not always favorable.

At one point, Sarah wrote that Earp threatened to whip children—including, perhaps, her own. The details are brief, as was her style, but the implication is clear: he had a temper and believed in discipline the old-fashioned way. To modern readers, this feels shocking and harsh, but in 1864, it wasn’t unusual.

Earp’s behavior was fairly common for the time. Discipline, especially of children, often came with raised voices and raised hands. A man like Nicholas, shaped by war and hardship, would have seen his role as head of the train—and his family—as one of control, protection, and order. His approach to leadership was informed by a world in which survival often depended on obedience. There was little room for backtalk or disobedience when you were facing down the deserts of Utah and Nevada, with limited water and no help for miles.

As the wagons moved south from Salt Lake City, they picked up the Mormon Road, a rough route that cut across the Great Basin and the Mojave Desert. This trail, used by Mormon settlers on their way to California, was dry, dangerous, and unforgiving. The group passed through Beaver and Parowan, Utah, into southern Nevada, and then down into the California desert, where their trials multiplied.

In her diary entry dated December 4, 1864, Sarah recorded a chilling stop near Salt Spring, on the southern edge of Death Valley. There, they found the remnants of a mining operation where three men had recently been killed—possibly by local Native Americans. Sarah noted the presence of four abandoned buildings and a quartz mill, and the unease in the camp was palpable. The group was vulnerable, tired, and on edge.

A short time later, they reached Bitter Springs, another desolate stop known for its sparse water supply. According to Sarah, local Native people approached the wagon train but did not attack—perhaps because of the size of the party, or perhaps because their intentions were peaceful. Still, the tension must have been thick in the desert air.

As the days wore on, tempers grew shorter. Food and water grew scarce. Animals began to falter. And the relationships among the travelers frayed. Nicholas Earp’s hardline leadership—so natural to him—probably became harder to tolerate under such conditions. His background, age, and sense of authority collided with the growing exhaustion of those around him. Sarah’s quiet observations hint at these dynamics, even if she never spells them out directly.

And then there was Wyatt Earp—just 16 years old, along for the ride with his family. Later, he would become one of the most iconic lawmen of the Old West, but during this journey, he was simply a boy on a horse. Sarah barely mentions him. He rode. He hunted. He wore out horses. He did not yet command attention. His father’s shadow was too long.

Eventually, the wagons followed the Mojave River, moving past waypoints like Camp Cady or Lane’s Crossing, before climbing the rugged terrain of Cajon Pass. From there, it was a descent into green hills and relative safety. In San Bernardino, they would find civilization—such as it was—and a temporary end to their troubles.

But that journey, and the roles people played in it, stuck. Sarah’s diary survived to tell the tale. In her pages, we see a woman navigating not just a trail, but a world of personalities, expectations, and power struggles. We see Nicholas Earp not as a villain or a hero, but as a man of his time—unyielding, protective, severe. We see the toll that hard roads take on even the hardest men.

And in the background, quietly riding along, was a teenager who would one day walk down a dusty street in Tombstone. But for now, he was just Wyatt—young, restless, and learning, perhaps unconsciously, what it meant to survive in a world ruled by men like his father.