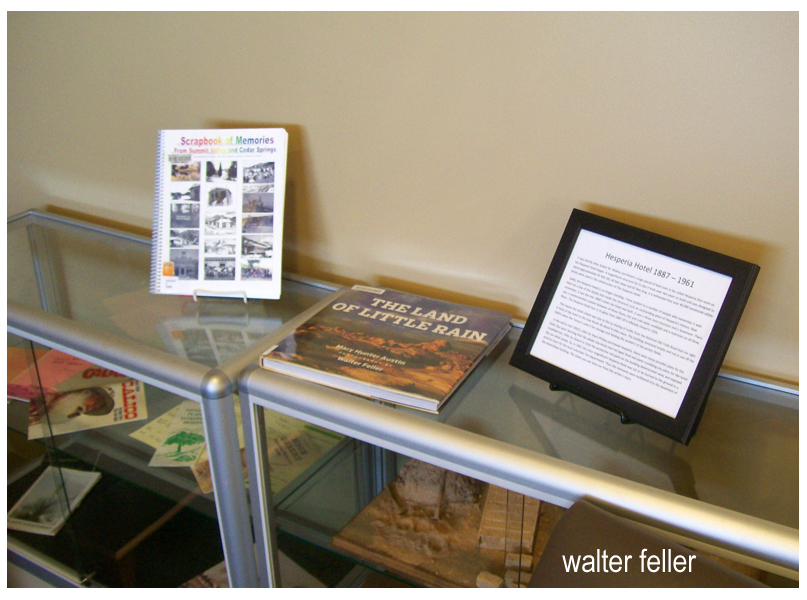

About 2009 I read an article titled “Cottonwood Springs” in the December 1959 Desert Magazine (50 years old) written by a gentleman named Walter Ford.

I wasn’t sure where the place was, although the photo included in the piece sparked some kind of vague memory. I couldn’t quite remember where it was though.

First, I thought maybe Cottonwood Springs in Joshua Tree National Park. Then again; how many places are named “Cottonwood Springs?”

A helluva lot more than two.

It is the same for many other places using common names; Arrastre Canyon, Grapevine Canyon, Round Mountain, etc. I have been told that there are 7 different ranges named “Granite Mountains.”

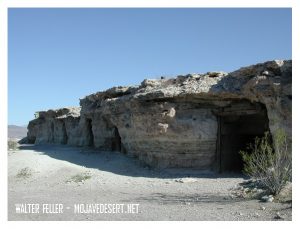

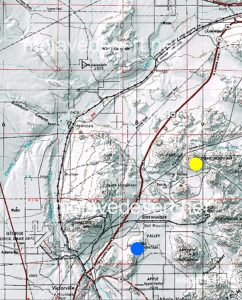

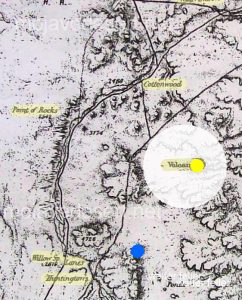

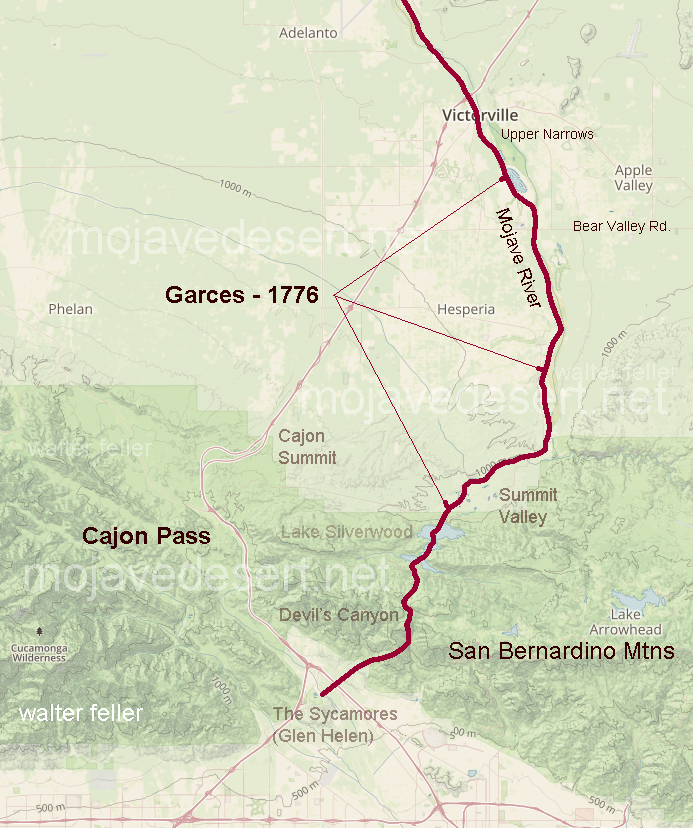

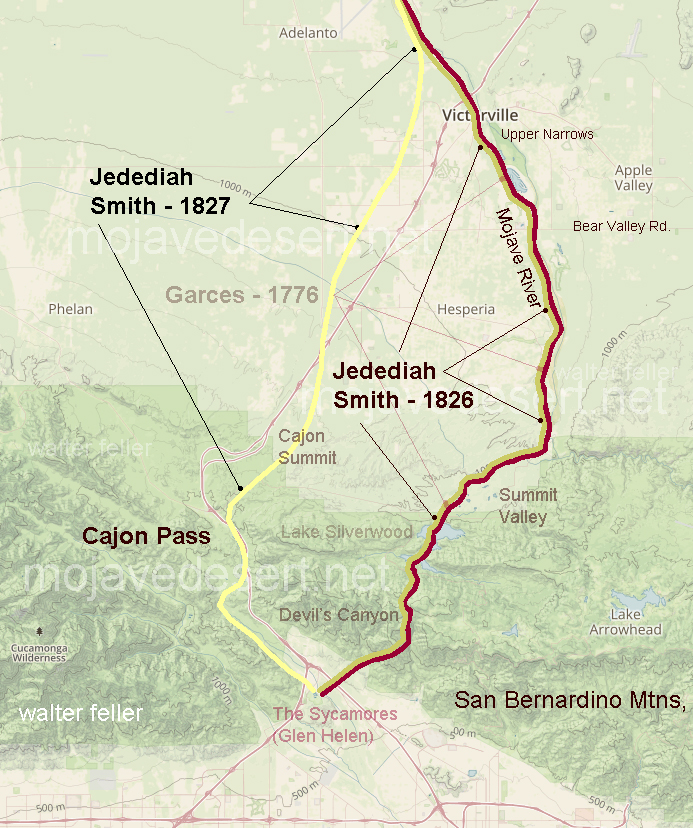

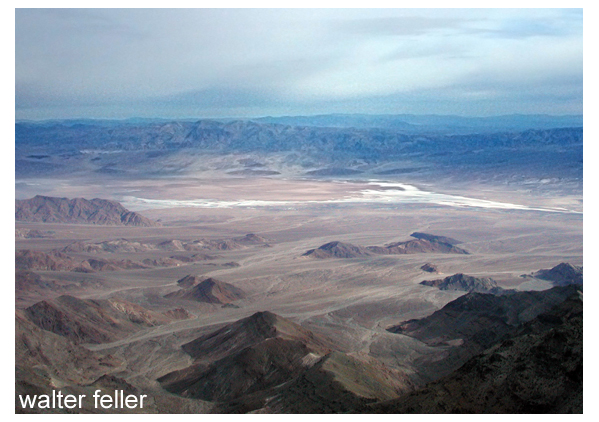

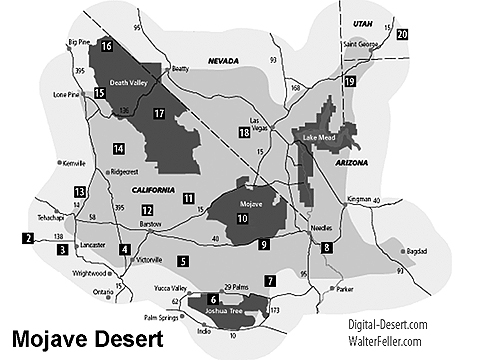

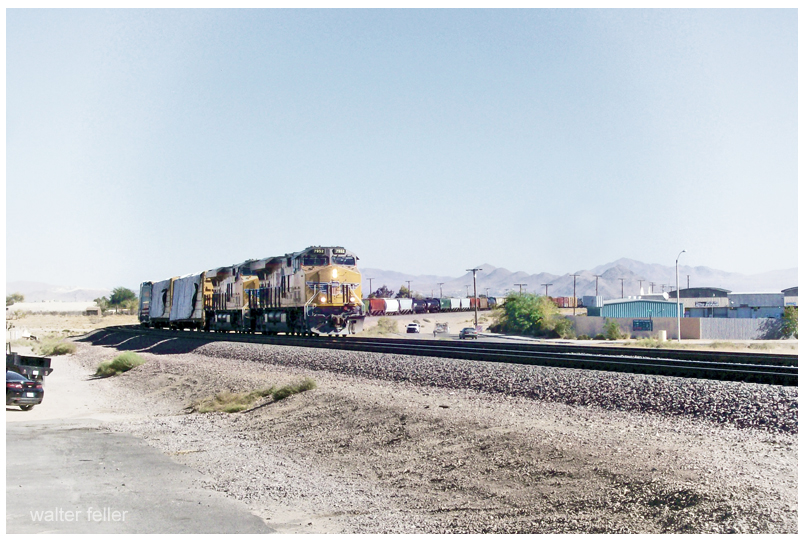

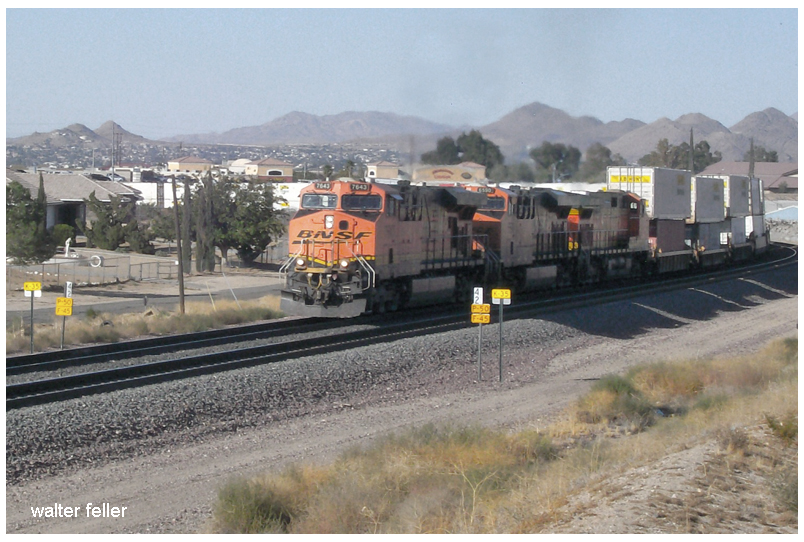

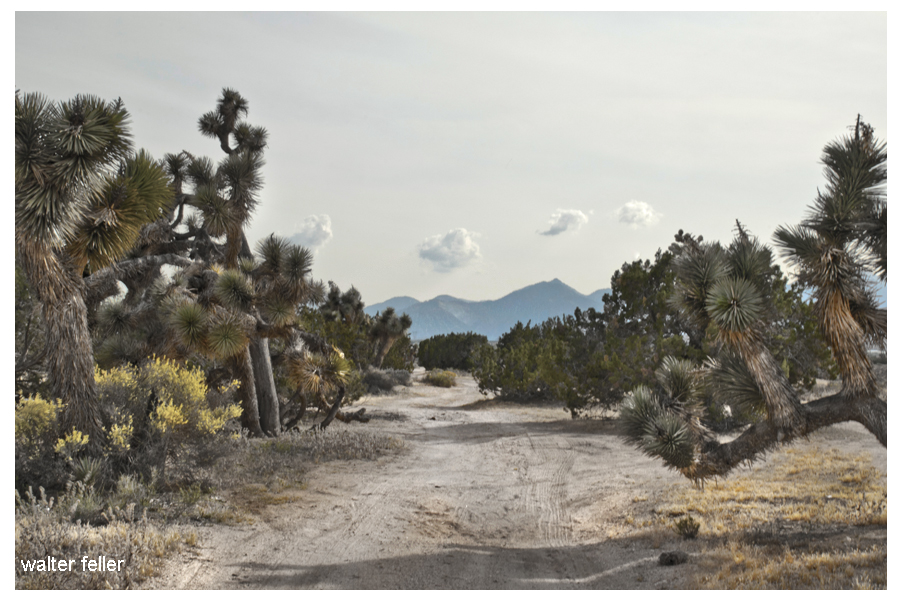

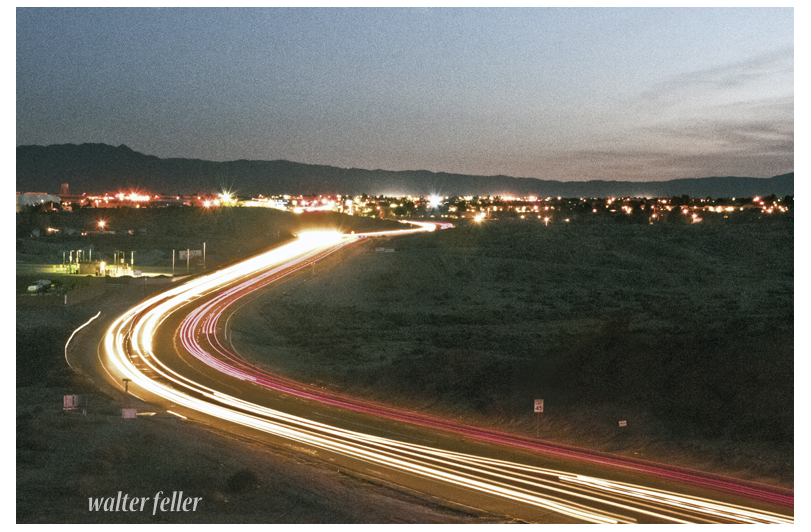

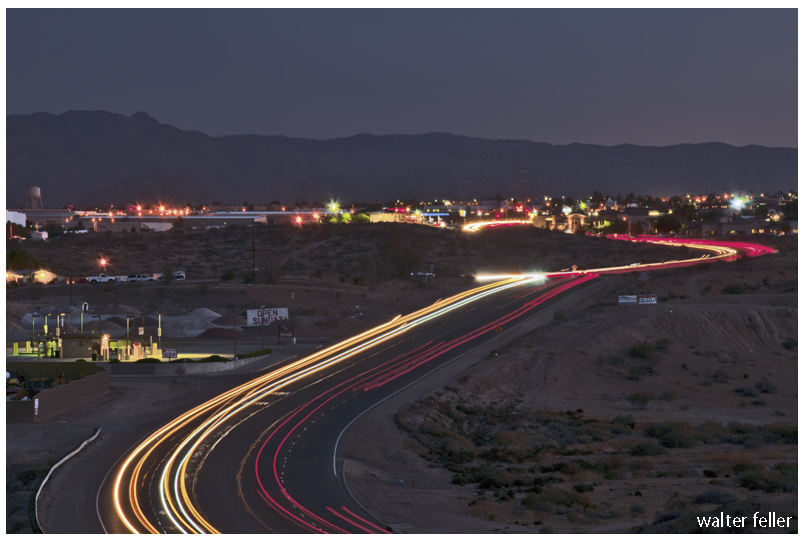

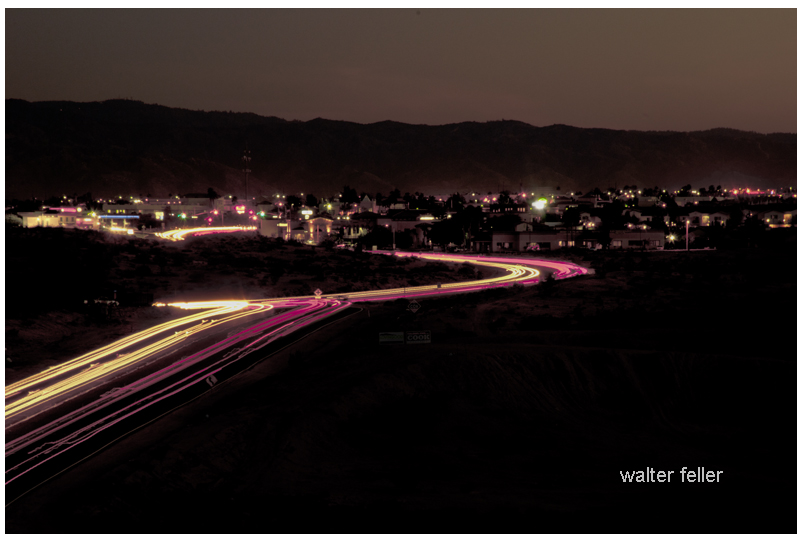

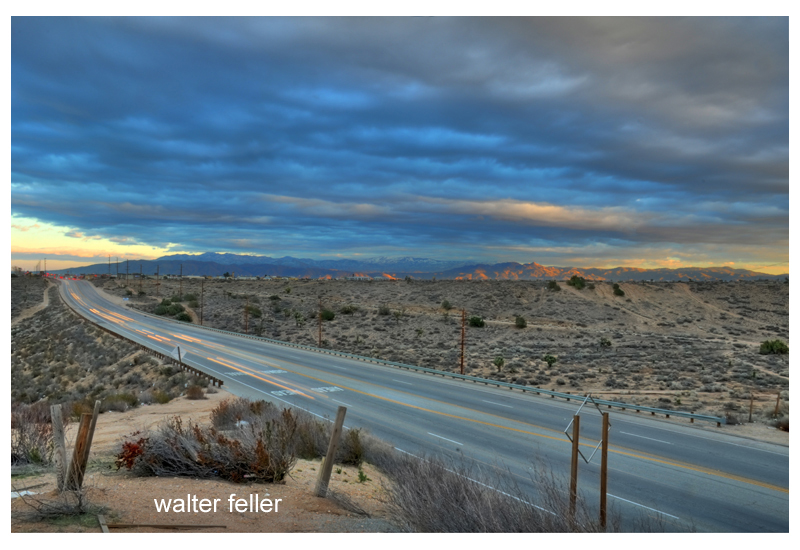

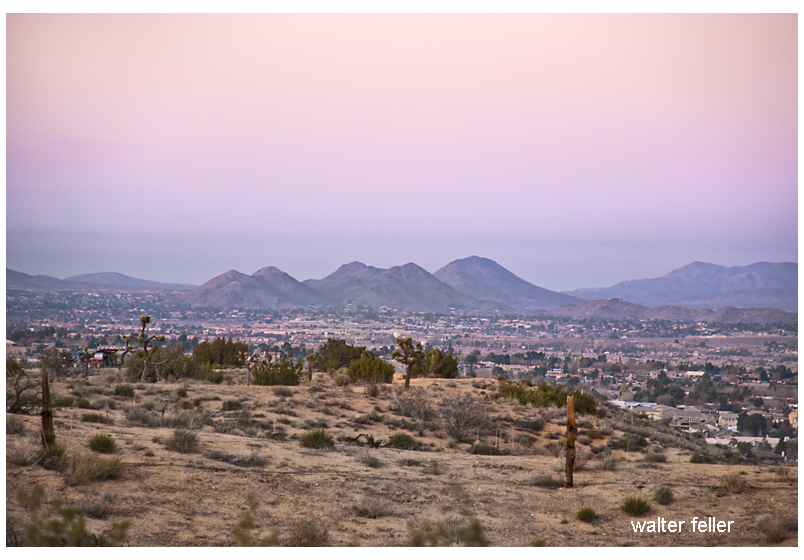

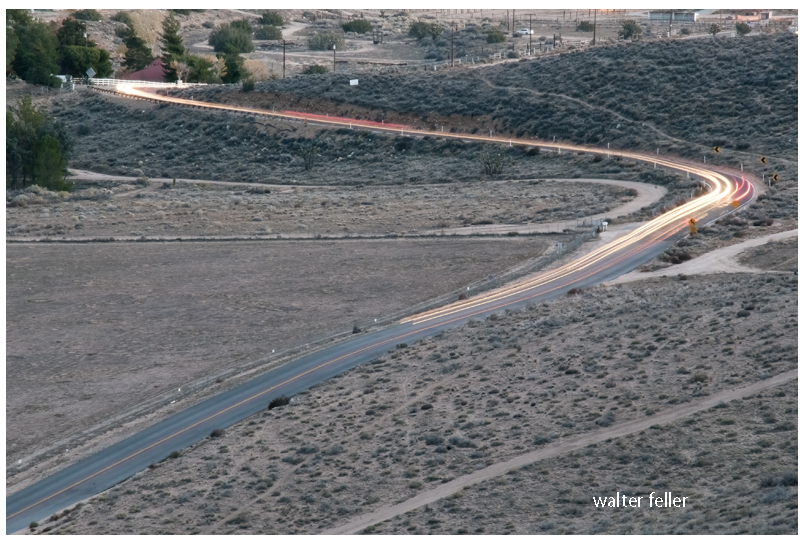

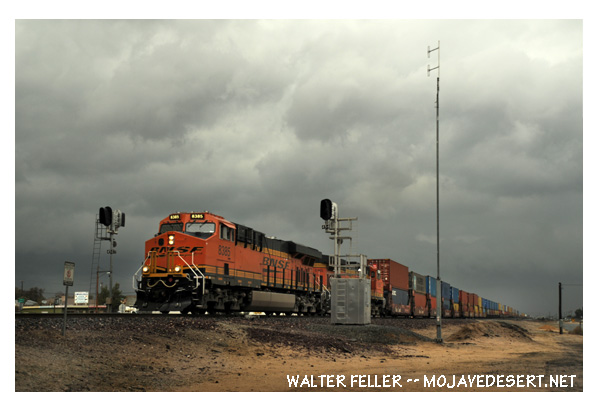

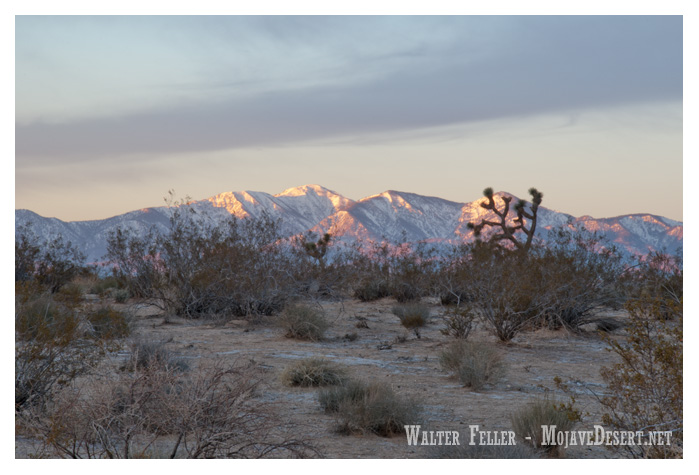

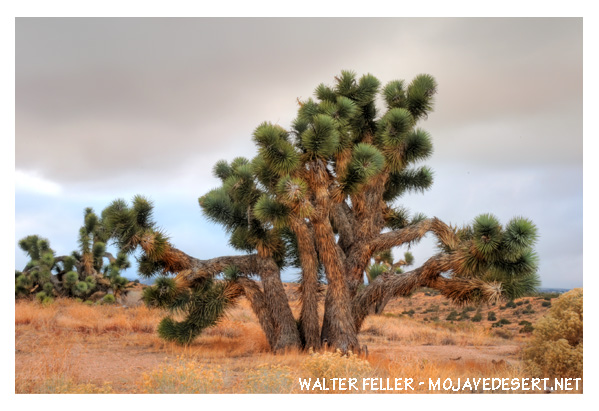

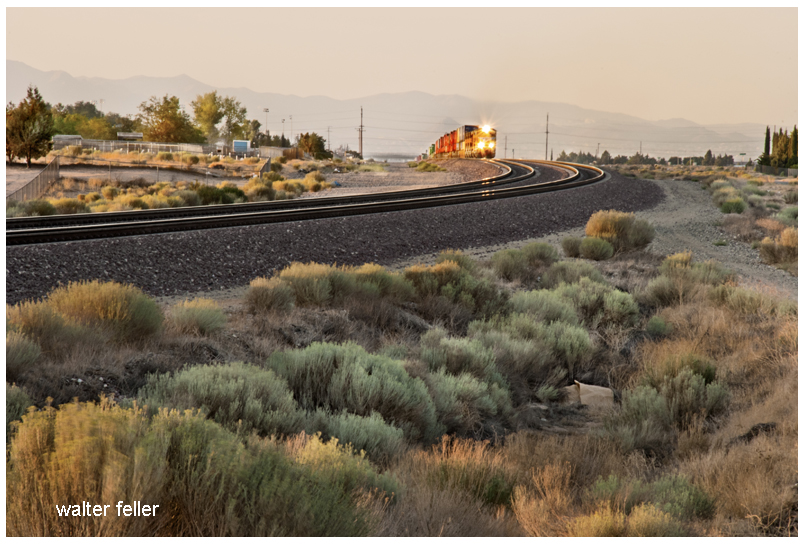

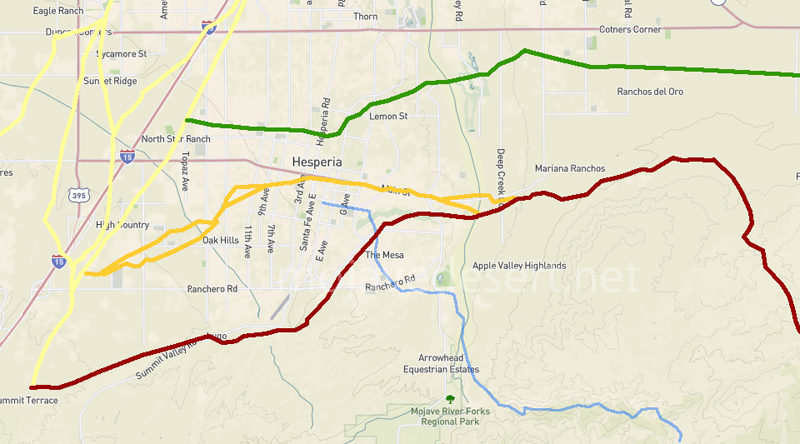

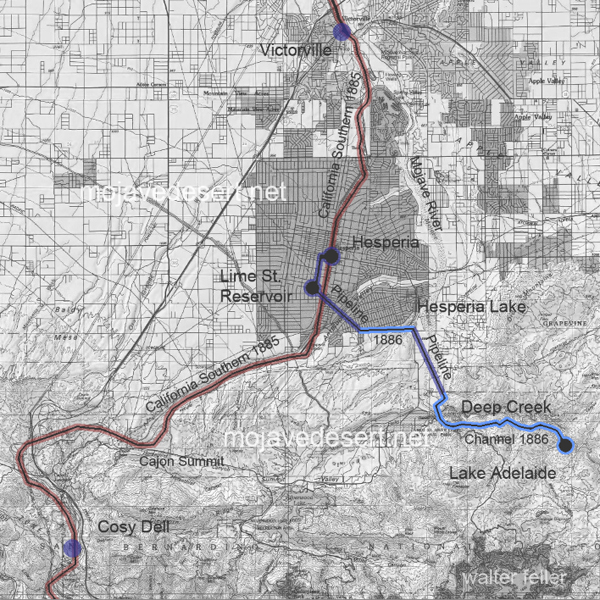

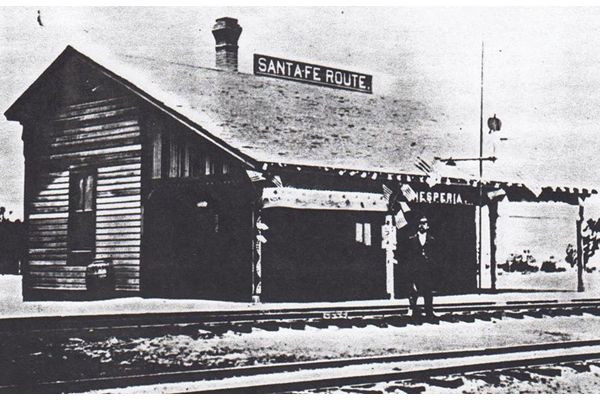

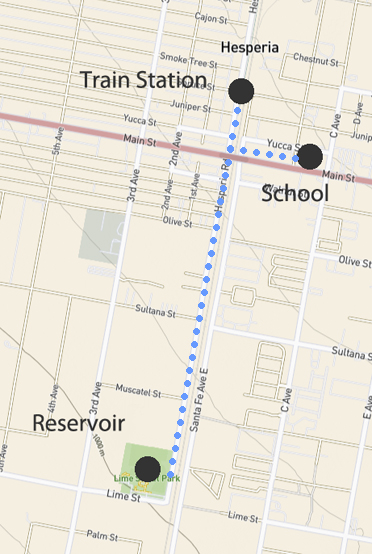

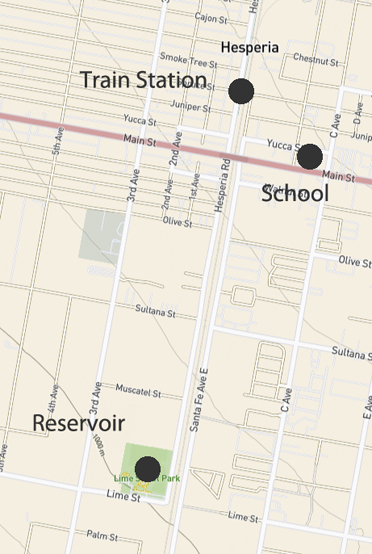

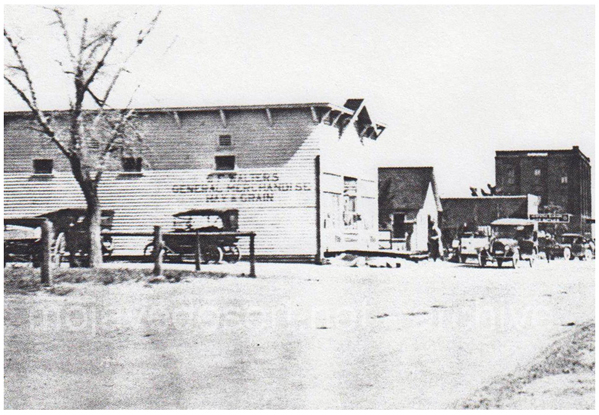

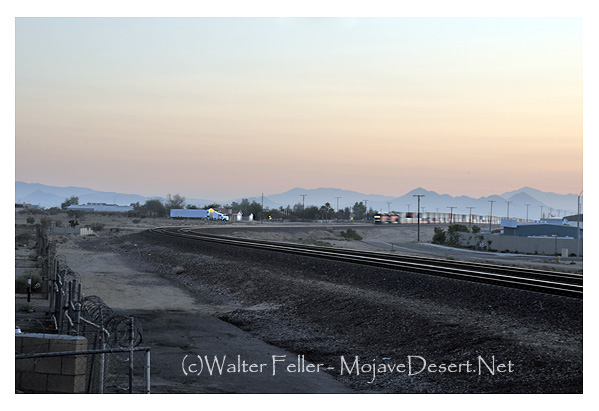

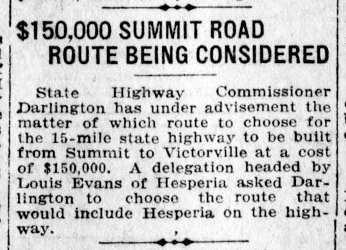

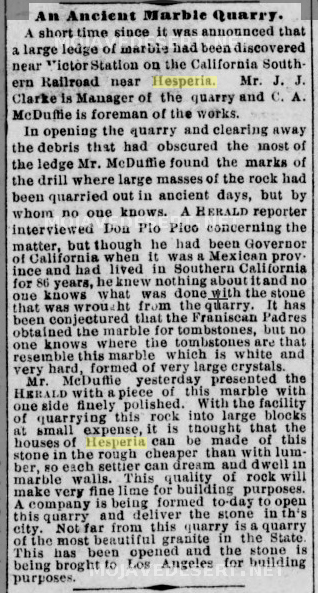

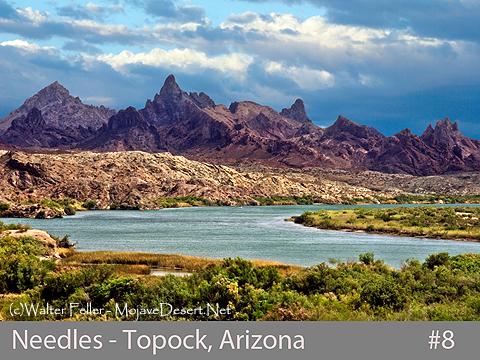

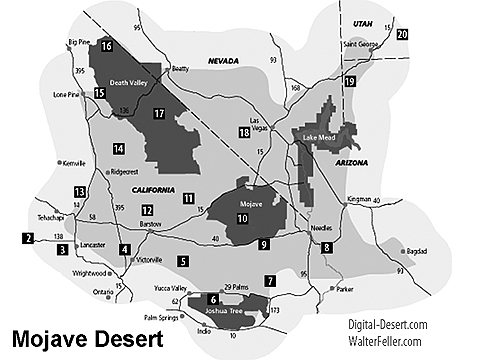

The springs were described as located along the Twentynine Palms–Victorville route. Mr. Ford mentioned speaking with A. W. Johnson, a long-time prospector of the area. Johnson said he was visiting the spring in 1914, and mention that you could find Indian artifacts such as grinding stones, broken pottery, and arrowheads being plentiful, and they were there for the taking. The author also mentioned a train running through the desert landscape and then making a sweeping, graceful turn near a sign that read Cottonwood Station. There’s only one place in the Mojave Desert that fit, and that was confirmed near the end of the article- Old Woman Springs. Eureka! I wondered though, why was the spring renamed Cottonwood Spring some 50 years ago, and again renamed Old Woman Springs?

The Old Women of Old Woman Springs

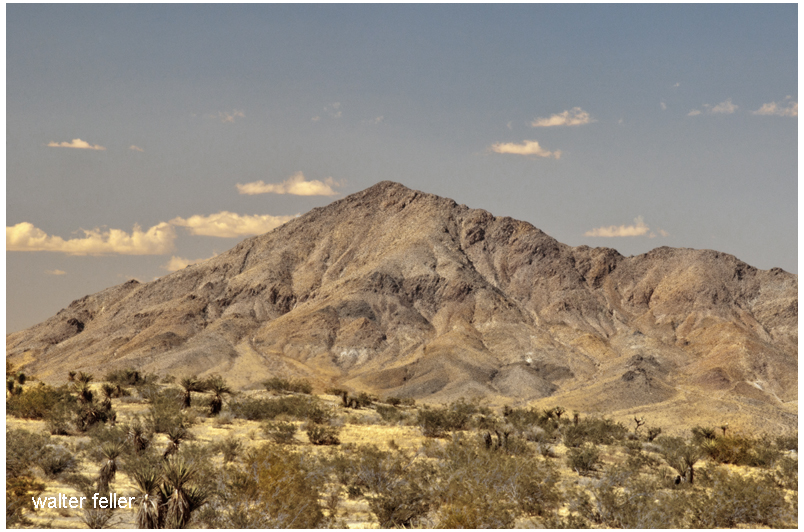

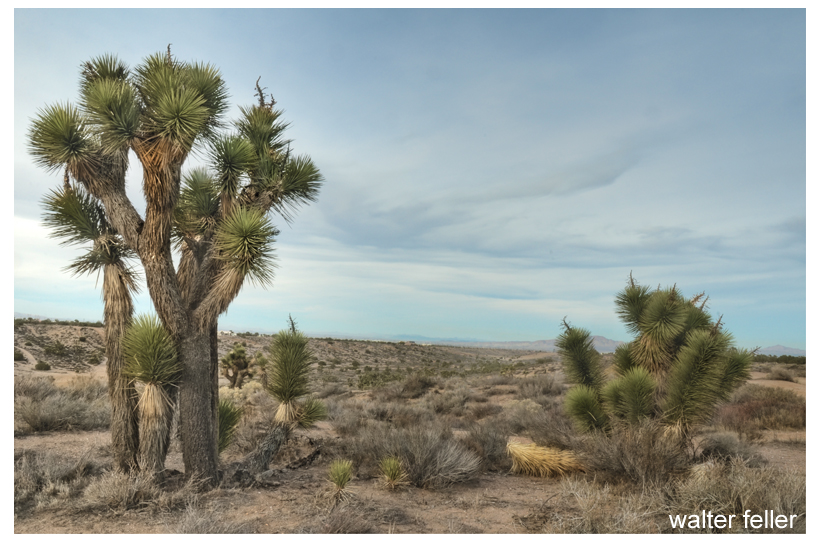

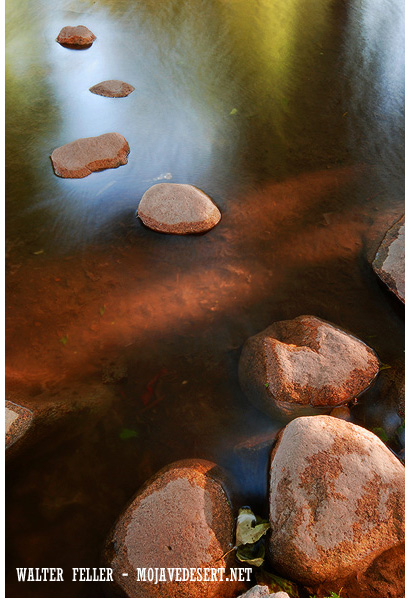

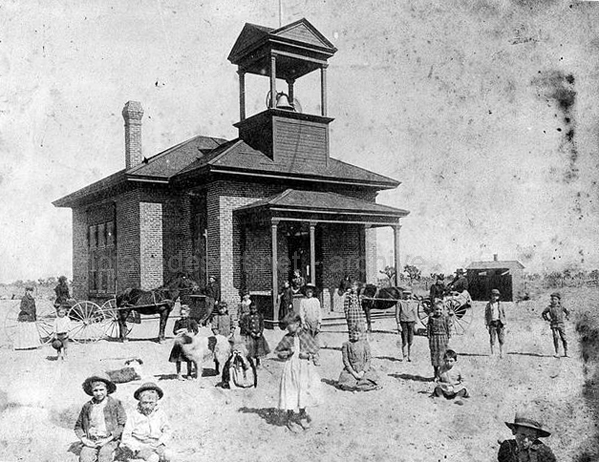

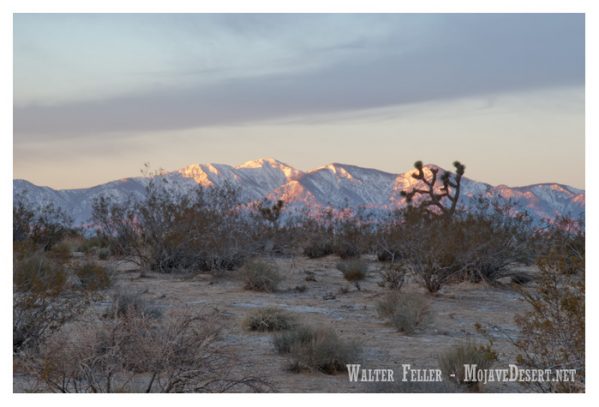

In 1855 Colonel Henry Washington of the U.S. Army came through the then-unnamed Johnson Valley surveying the baseline. Near the west end of the valley, he found two elderly Indian women alone at a spring. Names of places came cheap, and I’m sure someone thought the name was appropriate, so the name was recorded for all posterity to ponder. The two Indian women may have been left there to watch young children traveling with the band. The rest were probably in the nearby mountains gathering piñon nuts and hunting, as hunter-gatherers were known to do. The children may have been hiding—watching, as the curious party passed through the valley. The springs, as far as anyone knows, were quiet for

the next 40 or so years.

People & Places

It is through the people, within the times they lived, interacting with the land and their relationship to each other that we learn of and possibly understand the unique character of places in our desert.

Charlie Martin is to Albert Swarthout as Albert is to Dale Gentry. Dale Gentry is to Cottonwood Springs as Swarthout is to Old Woman Springs Ranch and Martin to the Heart Bar. Now that all that is out of the way, let’s begin in the San Bernardino Mountains with Charlie Martin and the Heart Bar Ranch.

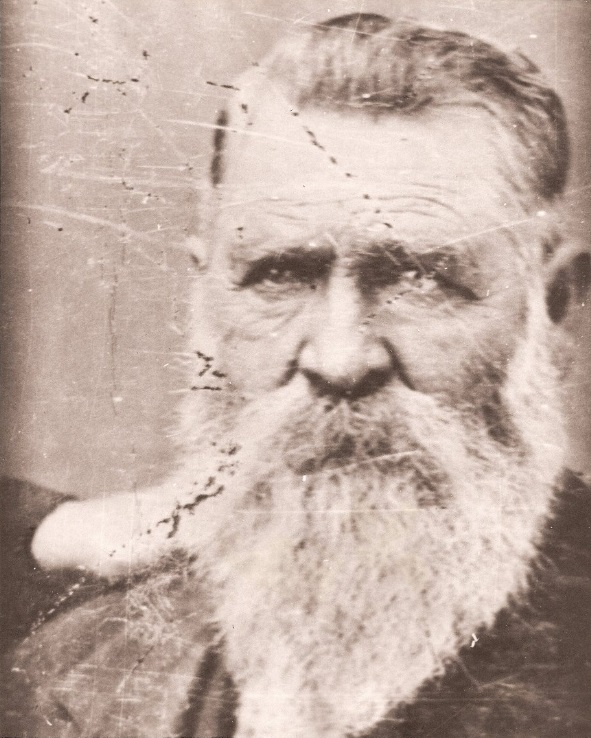

Charlie Martin

At over 200 pounds Charlie Martin was tough, as hard as a horseshoe, and ran with a dubious crowd. In Martha Wood Coutant’s book, Heart Bar Ranch, he was reported to have operated a resort for his criminal friends at his place in Glen Martin. Brothers Bill and Jim McHaney were frequent guests, and of the brothers, Jim would come to have his own gang after being run out of the mountains. Charlie, at one time a rustler and later a police chief of San Bernardino, is interesting to note that this apparent conflict in careers could have worked in the good citizen’s favor. Who else would better narrow the playing field of bad guys but the host of them all? Maybe that’s how Jim McHaney and his gang were forced to find a new range?

According to historian Willenna Hansen, Charlie killed at least two people. The first, after a loud argument, broke into a gunfight. Both combatants fired on each other. The victim kept missing Charlie and Charlie didn’t. The second killing was when Charlie was unarmed and approached a claim jumper known only as the Frenchman. He came after Charlie with a knife and started stabbing him. Charlie beat him off with his fists and made his way back to his wagon where he left his revolver. He shot the Frenchman square in the forehead without taking his gun out of the holster. There were no witnesses, so this time Charlie would be tried for murder. In court, his defense consisted only of him taking off his shirt for the jury to observe the 40-some, still-healing, stab wounds on his arms, chest, and back. The verdict returned was self-defense.

The Heart Bar Ranch

Charlie Martin had a number of irons in the fire. He came to believe that his fortune may lie in cattle ranching. He approached Mr. Button regarding a loan for $900. Button, possibly considering Charlie Martin’s reputation, decided he’d rather be his partner than loan him the money. It was in early 1884 when they registered the Heart Bar brand in San Bernardino. Over the next dozen years or so Martin had a variety of partners in the Heart Bar—however; nobody knows what may have come of Mr. Button.

Albert Swarthout

Albert “Swarty” Swarthout was born February 11, 1872, in San Bernardino, California. He was the youngest of five children born of George and Elizabeth Swarthout, Mormon pioneers who came to the area in 1851. George and his two brothers became cattlemen in the San Bernardino Valley. Albert never knew his father, because George died two months after he was born. It was too late; Albert already had cattle in his blood. He grew up dreaming of having his own cattle empire someday.

Swarty married Lillie Furstenfeld of Hesperia on February 10, 1895, at her parent’s house in Alhambra, California. Soon afterward they moved to Lucerne Valley and homesteaded what became the Box S Ranch. It didn’t take long for Albert to figure out the area was no place for a cattle ranch. They moved back to San Bernardino where he used his family’s connections to get a job as a forest ranger. He used the opportunity to become familiar with the mountains and meadows in the San Bernardino Mountain Range.

The Old Woman Springs Ranch

Al Swarthout, after giving up his claim to the Box S, homesteaded Old Woman Springs. With a 400 acre ranch and rights to 1600 acres of grazing being used as winter range for the Heart Bar in mind, Swarty was poised to begin his cattle empire. Martin and Swarthout entered into a partnership in 1907.

There were good years and bad years, and a few in-between years. The Swarthouts lived at the Heart Bar headquarters at Big Meadows during the summer and moved down to Old Woman Springs in the winter, driving stock back and forth through Rattlesnake Canyon between the two ranges. Charlie and Swarty seemed to get along pretty well, and Charlie took to Al’s son Donald becoming quite the uncle, taking him camping and riding often. Charlie tired of it all, and in 1914 sold off his share of the ranch to Albert’s next partner.

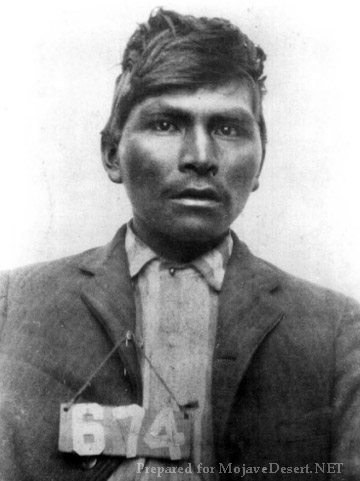

The Manhunt for Willie Boy

Swarthout kept a tight, hardworking outfit. Those who worked for Swarty liked and respected him, and he treated them as friends. Willie Boy, who in 1909 killed his fiance’s father and became the subject of the last manhunt in the area, according to V.C. Hemphill-Gobar in her book, Range One East, had worked for Swarty. She continues that it had been rumored he stopped by the ranch looking for help. Swarty said he wished he had been there for him. He felt he may have been able to talk Willie Boy into giving up without further bloodshed. Al wasn’t bragging, he knew and was friends with the ranch hand turned desperado. The reader should note that this subject in itself is controversial, with some believing that Willie Boy made good on his escape and lived to old age as a rancher in Nevada.

Steady Development through Tumultuous Times

After another series of partner changes in Heart Bar Ranch ownership, Swarty took an out in 1918. However, in 1922 Swarthout and Dale Gentry formed a partnership and bought the

ranch outright between them.

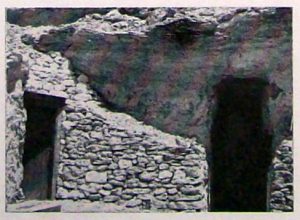

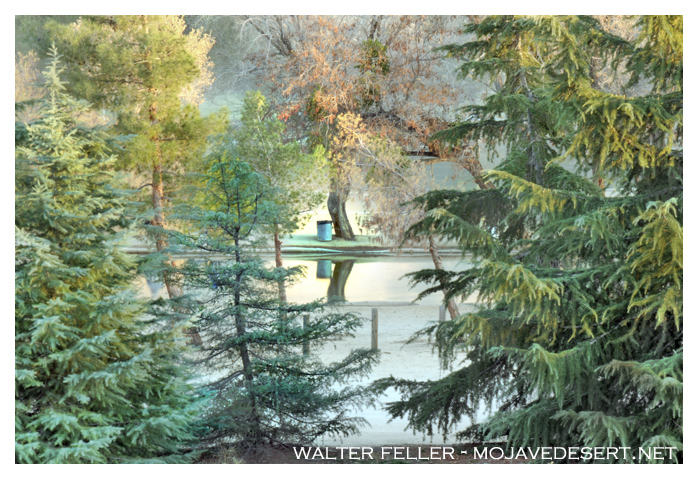

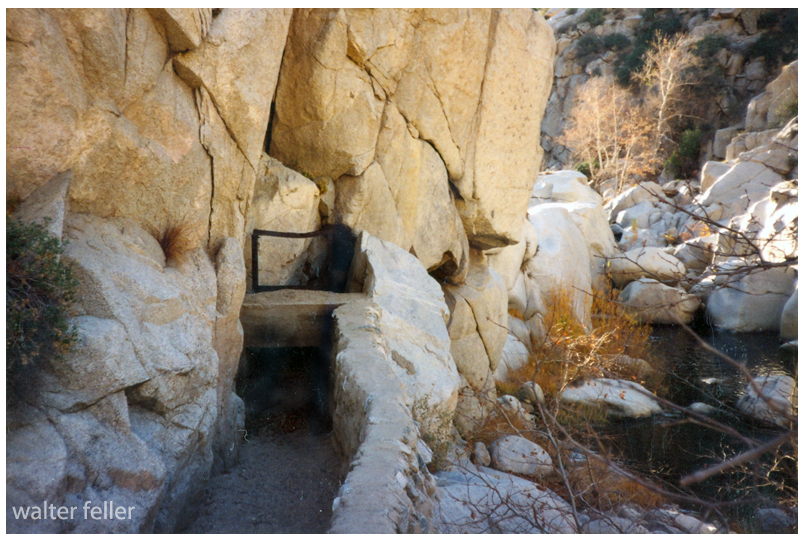

Over the years before, and during the years after this final partnership was formed, Swarty developed the ranch property; more buildings were built, springs and wells developed, and a field of alfalfa maintained. Even with this much water available, no more than 12 acres of alfalfa could be grown. Martha Wood Coutant states, “It would get so hot, and the crop would have to be harvested by hand quickly before it ‘shattered’ and became useless to cattle.”

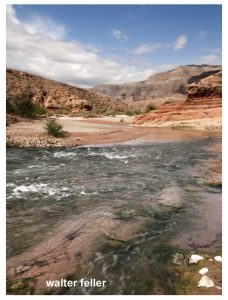

Swarty and his friend Julian “Junie” Gobar from Lucerne Valley had figured out a clever irrigation system wherein the most productive spring produced roughly 150 miner’s inches (nearly 1700 gallons per minute) of water flow. The accomplishment was highly regarded by hydraulic engineers of the day.

By 1938 the end of the Heart Bar was unavoidable. The price of beef was down and stack was getting mixed in with the herds of other ranches. Many cattle were dying from drinking water poisoned by the cyanide from gold recovery operations further up the mountain. Swarthout and Gentry were arguing and agreed to bring it all to an end. The ranch went into litigation. However, a decision regarding the properties wasn’t reached until 1947. It was decided Gentry would get the Big Meadows property in the mountains and Swarthout the Old Woman Springs property in the desert. Swarty thought it was fair—Gentry did not. Albert agreed to trade halves straight across. The deed was drawn up, done and both went their separate ways. Albert Swarthout at the time was in his mid-70s and still a very active individual. He and Lillie stayed at Big Meadows until 1952, after which they moved to San Bernardino.

Dale Gentry

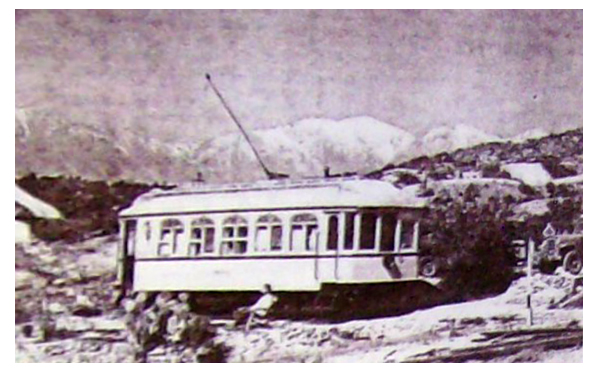

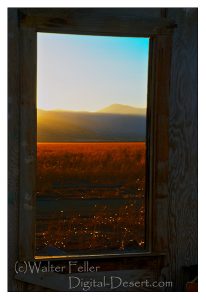

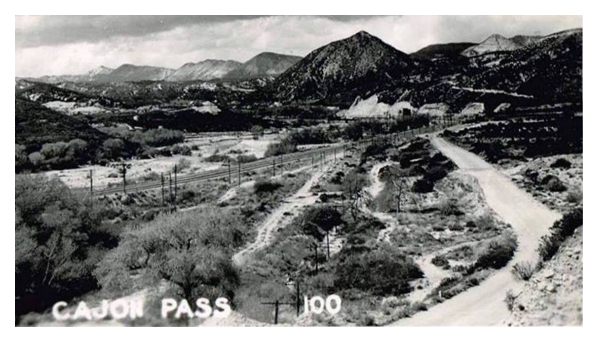

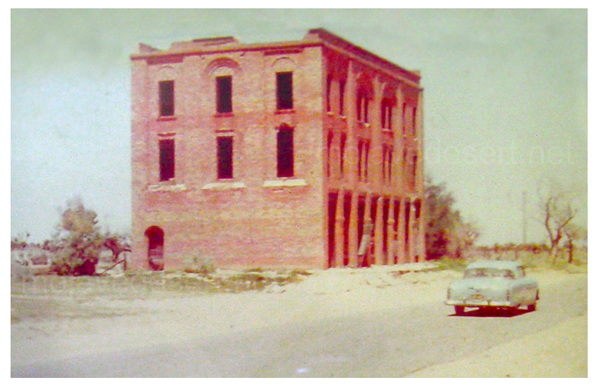

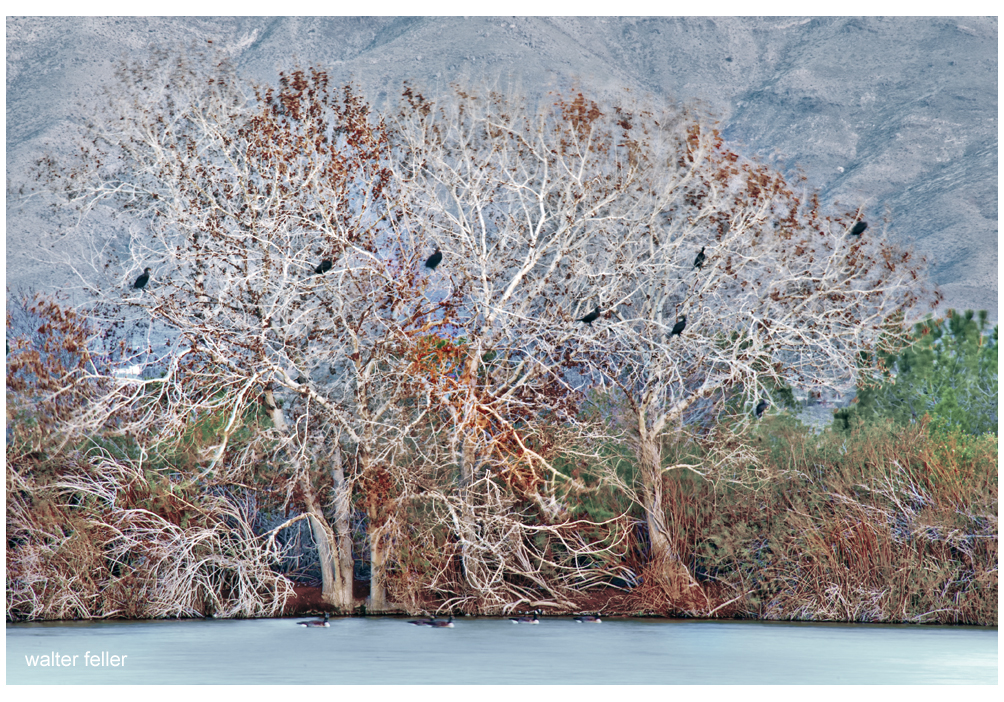

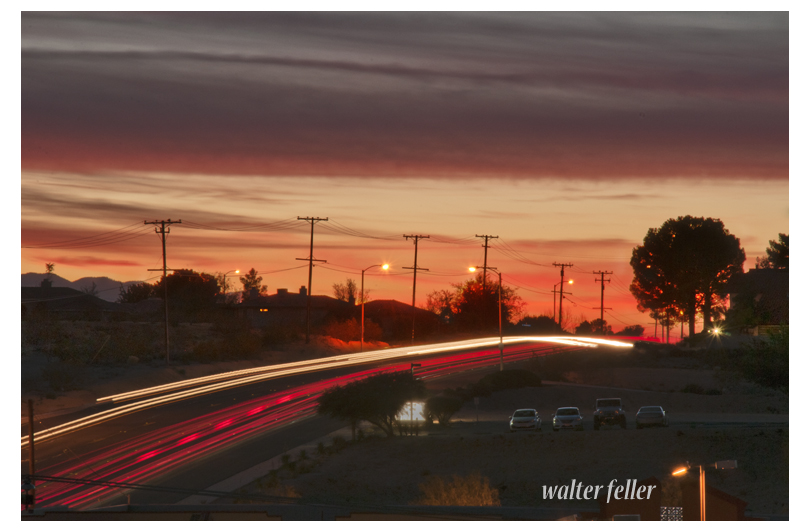

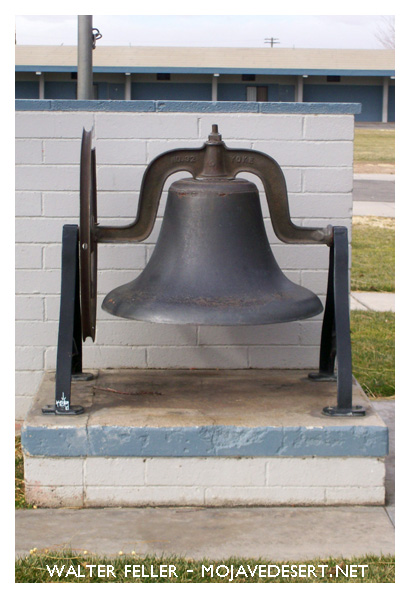

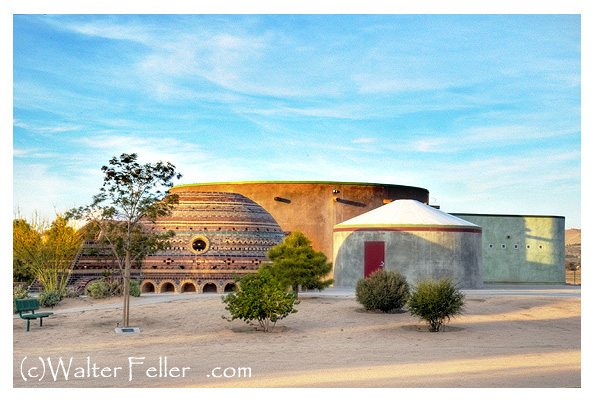

Throughout the 1950s Dale Gentry was the owner of the Old Woman Springs Ranch. There was plenty of water and 400 acres of land to do with as he wished. As a young man living in Hawaii, he had worked on a pineapple plantation. He admired the steam-powered locomotives that carried the product in from the fields. Now that he had the money and the room for it, he purchased an engine, tender, two flat cars a boxcar, and a caboose. They were brought to the ranch along with ten miles of narrow gauge track. Next, a water tower, depot, and roundhouse were built, and Gentry enjoyed giving rides to his visitors at the ranch.

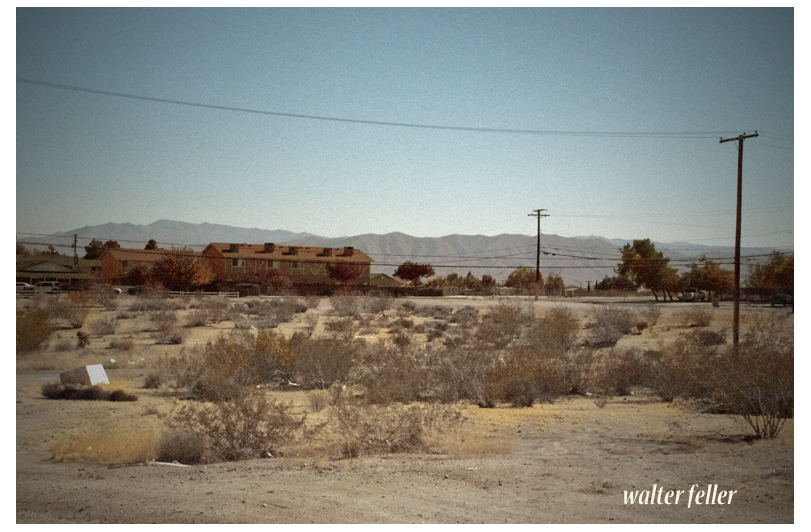

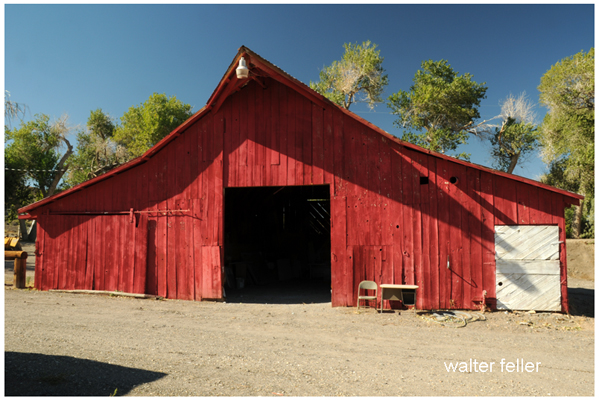

Other than six or so railroad ties found embedded in the dirt service road awhile back, there is no trace that Gentry’s “Cottonwood & Southern Railway”, ever existed. There are the buildings; the water tower, a depot, the engine room, but when I first toured the ranch in the late 1990s I figured they could be the result of another wild-eyed desert story—Of course they are.

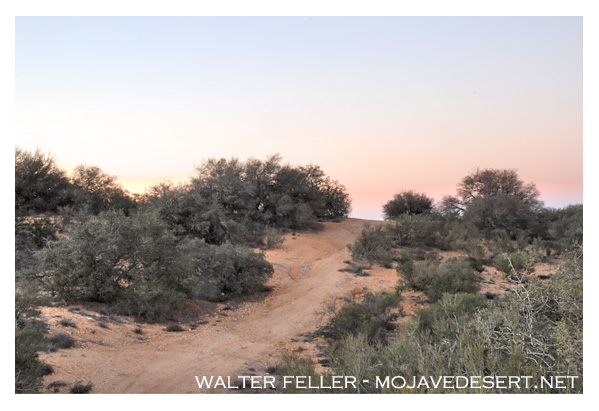

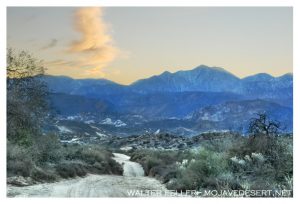

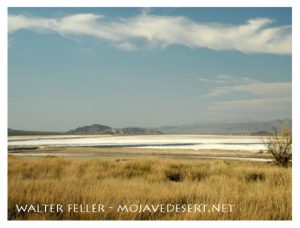

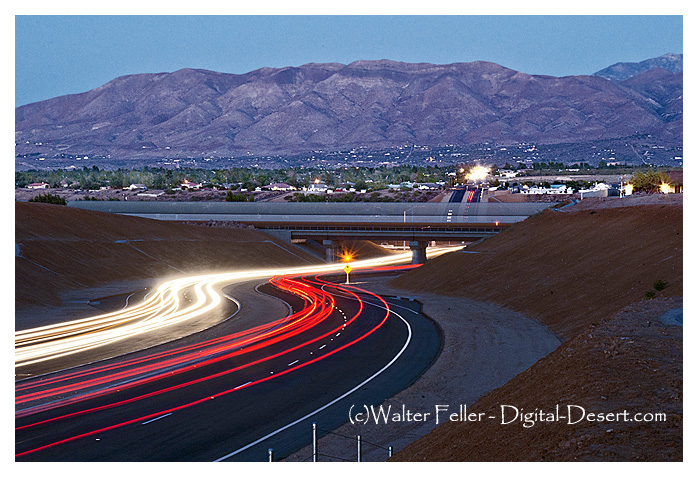

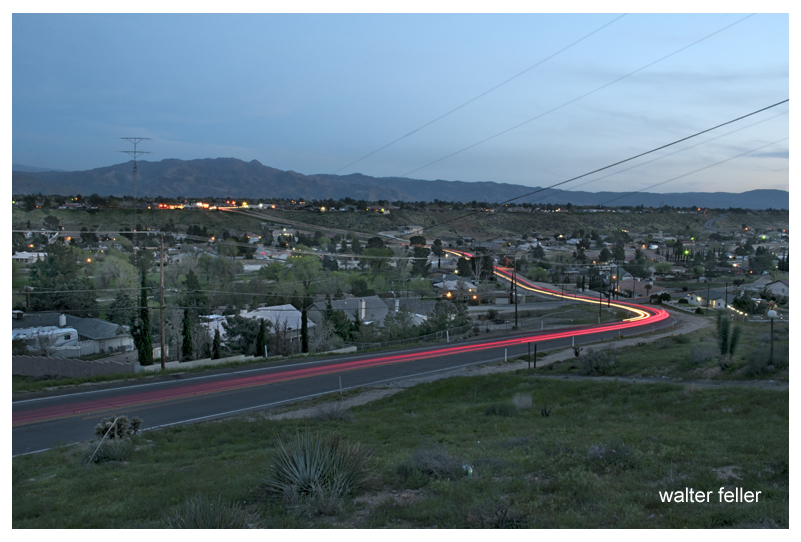

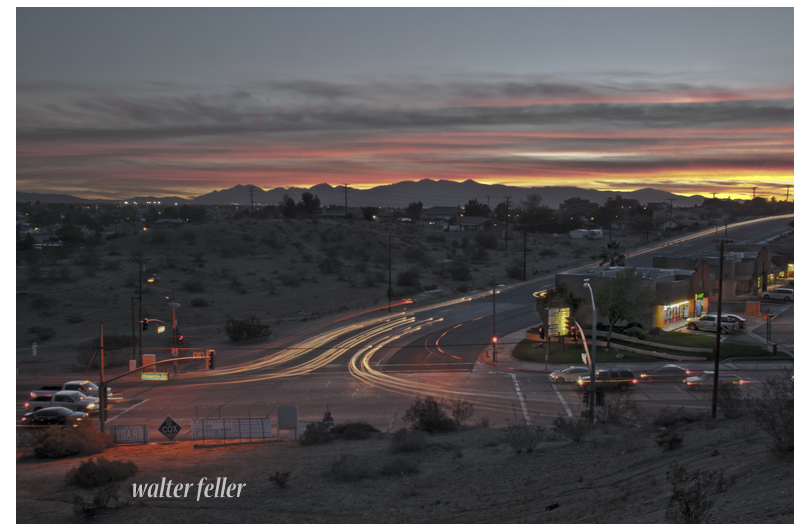

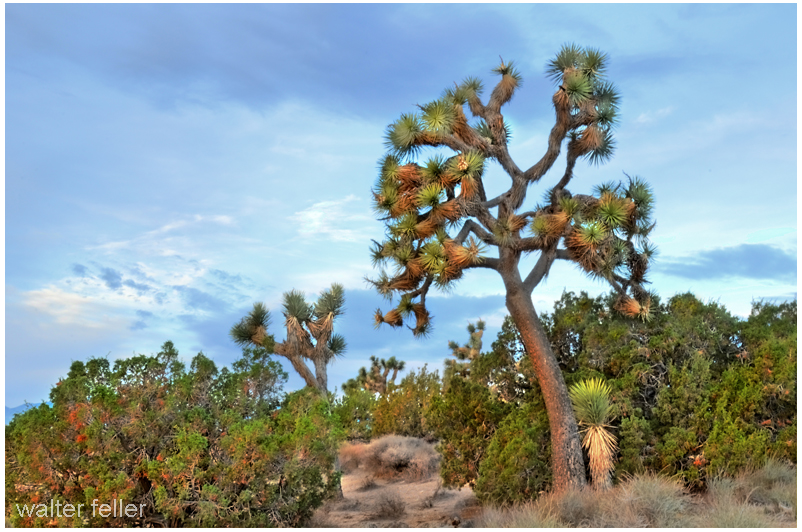

Closing the Gate

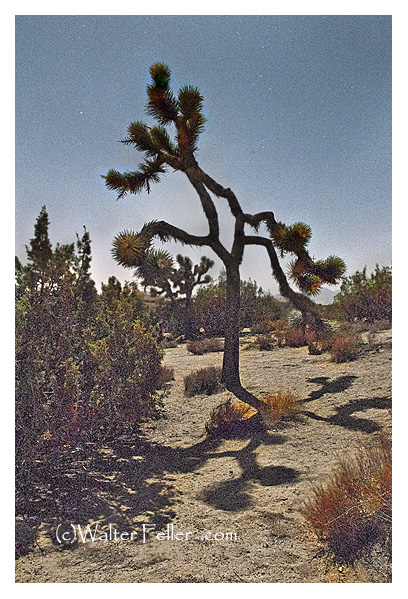

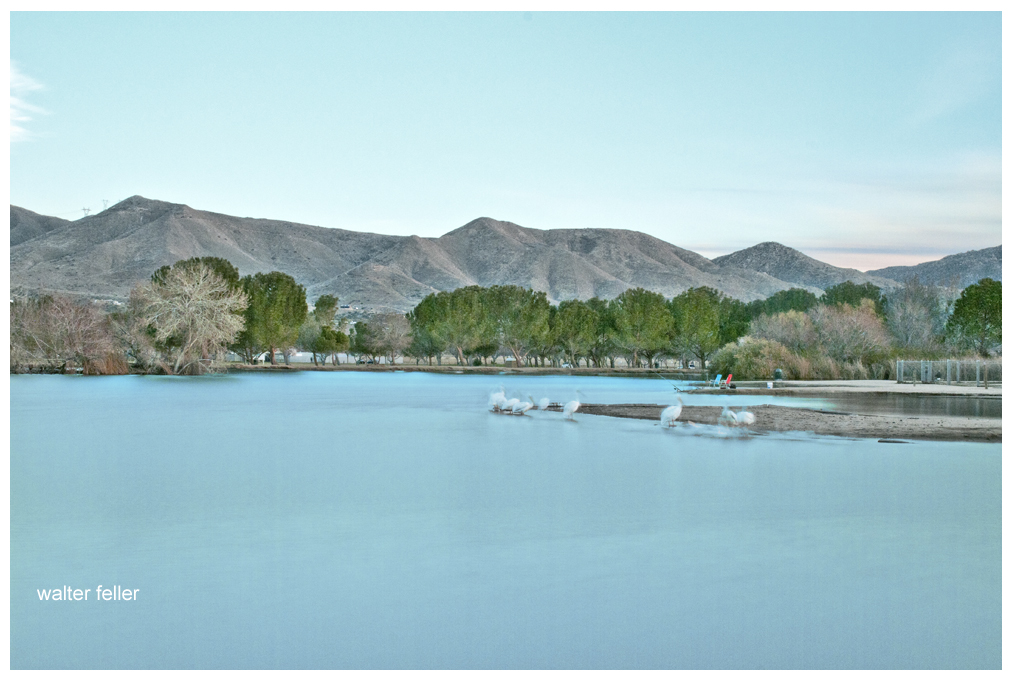

From the highway, the ranch looks much the same as it could have 100 years ago when it was a part of Swarty’s dream brought to reality. It’s not a stretch imagining him among the cottonwoods with his friend Junie figuring ways of getting more water to more cattle on the range. Not long ago one may be able to imagine Dale Gentry’s steam engine gracefully rounding the curve, hauling a dozen or so happy passengers out to his station at the renamed Cottonwood Springs. Perhaps from there, with little effort, could look further back in time, hundreds, or maybe even a thousand years, when hunter-gatherers would leave their mothers to watch over the children while they went into the mountains for food.

Charlie Martin passed away in 1927 of cancer after serving several years as Chief of Police of the City of San Bernardino.

Albert Swarthout died November 10, 1963, at the age of 91.

Dale Gentry seems to have driven his train off into distant and dusty memories.

And, nobody knows what may have come of Mr. Button.

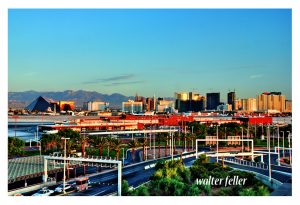

The Old Woman Springs Ranch is a private property located in the Johnson Valley, 15 miles east of Lucerne Valley on State Route 247, the Old Woman Springs Highway.

adapted from

~ Cottonwood Springs — Desert Magazine – April 1959 – Walter Ford

color photography by Walter Feller