from; Death Valley Historic Resource Study

A History of Mining – Volume I

Linda W. Greene

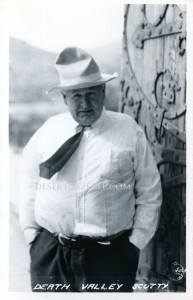

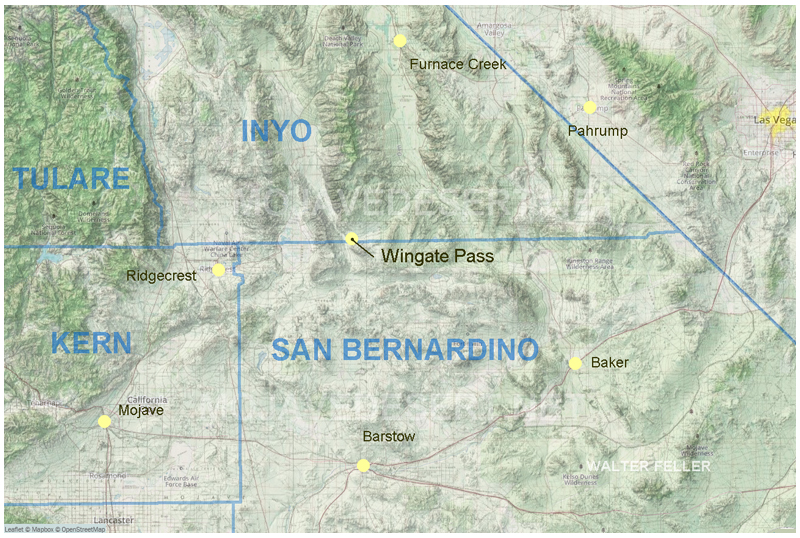

Probably the most publicized event in the Wingate Pass area concerns one of Death Valley Scotty‘s most infamous hoaxes, referred to as the “Battle” of Wingate Pass. Conceived as a last-ditch effort to discourage further investigations by a mining engineer who was insisting on actually seeing Scotty’s bonanza gold mine before recommending that his employers invest any money in it, the attack turned out to have almost fatal consequences for one of Scotty’s brothers, put Scott himself in and out of jail several times during the ensuing months, and ultimately, six years after the incident, resulted in his confessing in a Los Angeles courtroom to long-term and full-scale fraud and deceit. (The most concise version of this tale appears in Hank Johnston, Death Valley Scotty: “Fastest Con in the West” and serves as the basis for the following account.)

The escapade had its beginnings in February 1906 when a New England mining promoter, A.Y. Pearl, whom Scott had met in New York, interested some bankers and businessmen in investing in Scott’s supposedly rich mining properties in Death Valley. Before committing any money, however, the Easterners insisted that Daniel E. Owen, a respected Boston mining engineer who happened to be in Nevada at this time, personally inspect the property and give his opinion of its worth.

Arrangements were accordingly made with all the parties involved, and by February 1906 Owen, Pearl, and Scott were in Daggett preparing for the journey into Death Valley. Other members of the expedition were: Albert M. Johnson, president of the National Life Insurance Company of Chicago (soon to become Scotty’s long-term benefactor), who had recently arrived from the East and, intrigued by the stories of Scotty’s untold wealth, asked to accompany the party; Bill and Warner Scott, brothers of Death Valley Scotty; Bill Keys, a half-breed Cherokee Indian who had prospected with Scott in the Death Valley region for several years, who had found the Desert Hound Mine in the southern Black Mountains, and who several years later, after the “ambush” incident, moved to a ranch in what is now Joshua Tree National Monument [park]; A.W. DeLyle St. Clair, a Los Angeles miner; and Jack Brody, a local desert character.

The entire trip, if carried out as planned, had the potential of proving extremely embarrassing for Scott, who, after all, did not have a mine to show in order to consummate this lucrative transaction. Desperate for a solution, he turned to his friend Billy Keys and persuaded him to let him show Owen the Desert Hound instead. Although not as large as Scott had reported his bonanza to be, at least the Hound was there on the ground for Owen to see. Papers of agreement were drawn up to the effect that Scott and Keys would split the proceeds from the mine sale.

Later, fearful that Owen would reject this mine as being too small a producer to warrant investment by his employers, Scott devised a scheme that he hoped might succeed in scaring Owen away from the area and dampening his enthusiasm for penetrating into the Death Valley region as far as the mine. A shootout would be staged and hopefully be authentic enough to disrupt Owen’s intended mission.

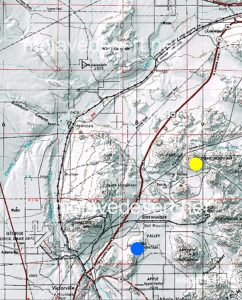

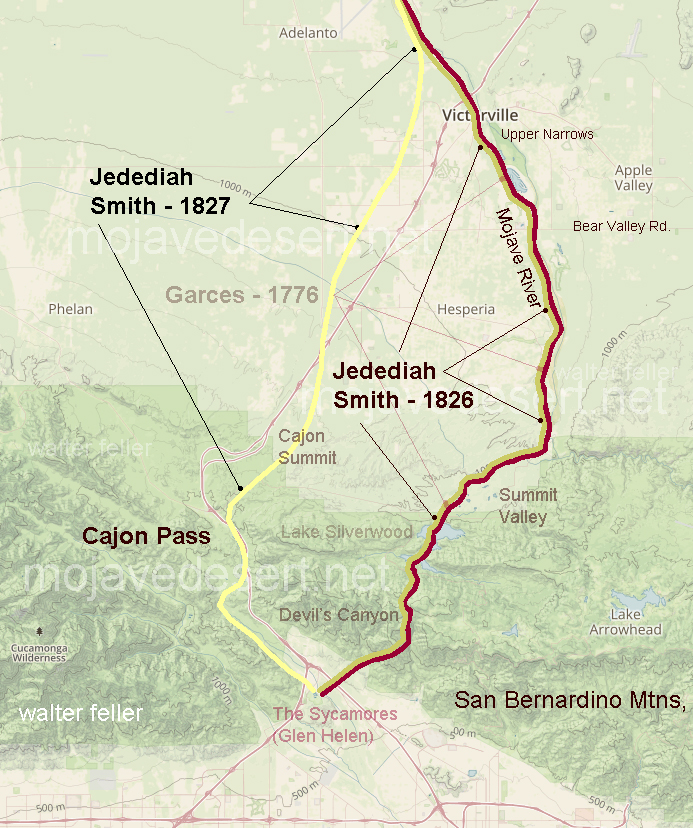

Starting out on 23 February 1906 with two wagons fully loaded with provisions, extra animal feed and fresh water, and a string of extra mules and horses, plus a liberal supply of whiskey, the party journeyed on to camp the next evening at Granite Wells. On Sunday, 25 February, the caravan pushed on twenty-six miles toward Lone Willow Spring, site of their next camp. In the morning Scott directed his brother Bill to stay at the spring with the extra animals and told Bill Keys and Jack Brody to proceed on ahead and look for any danger. After giving these two a reasonable head start, the rest of the party began the trek toward Wingate Pass and, surmounting that obstacle, proceeded on down the wash into the south end of Death Valley. Toward dusk that evening, as the party was trying to decide where to camp, shots were heard and a lone rider appeared from the north. He turned out to be an ex-deputy sheriff from Goldfield, Nevada, who excitedly reported that he had just been fired on from ambush and his pack train stampeded.

Receiving Scott’s assurances that he could fight off any outlaws, the party warily resumed its journey. A little further up the road beyond Dry Lake, near the site of the earlier shooting, Scotty suddenly drew his rifle and fired two shots. Startled, the mules pulling Warner Scott and Daniel Owen in the lead wagon began to buck, the force tipping Owen over backwards; a sudden shot from behind a stone breastwork on a cliff to the south hit Warner in the groin. It was at this point that Scotty made the fatal blunder that, in the recalling, forced Owen to doubt the authenticity of the ambush. Upon realizing that his brother had been seriously wounded, Scotty, nonplussed, galloped away toward the “ambushers” yelling at them to stop shooting.

Establishing camp quickly, an attempt was made to close Warner’s wounds. In the morning the party headed the wagons quickly back toward Bill Scott and Lone Willow Spring, and eventually toward Daggett, leaving their provisions behind by the side of the road. Keys and Brody never did rejoin the group. Reaching Daggett on 1 March, the group put Warner on a train for Los Angeles; Scotty hurriedly took off for Seattle where he was about to star in a play, “Scotty, King of the Desert Mine.” Johnson left immediately for Chicago and, due to some fast legal work by his lawyer, was not involved in any of the ensuing litigations.

The incident struck the fancy of Los Angeles newspapermen, who, however, were hard put to locate the principals involved or determine the true facts of the case. Pearl circulated a good story of fighting off four outlaws, but Owen, disaffirming this tale, and evidently convinced that Scott had meant to kill him, reported the true facts to the San Bernardino County sheriff and later to the press. Two weeks later warrants were issued for the arrest of Walter Scott, Bill Keys, and Jack Brody on charges of assault with a deadly weapon. In an attempt to determine the identify of the party’s attackers, the San Bernardino County sheriff, John Ralphs, and an undersheriff entered the Death Valley country to find Keys and Brody. Although these two managed to elude the law this time, the provisions that had been hurriedly left at the scene of the attack by the Scott party were found at Scotty’s Camp Holdout; other incriminating evidence took the form of a statement by Jack Hartigan, the Nevada lawman who had also been shot at, that he had backtracked and seen Keys running from the scene after Scott’s plea to stop shooting.

Publicity given to Scotty and the incident was becoming unfavorable, many people now deciding it was time to show Scotty up for the fraud and liar he was believed to be Scotty, working in his play out of town while loudly condemning these attacks on his character and reputation, continued to propogate the story of a bona fide attack by outlaws who were after his life and his valuable claims. Sarcastic poems and invective cartoons began to appear in the Los Angeles Evening News his primary accuser, which had earlier asked in an editorial, “What is the truth about this desert freak? He has ceased to be a joke. People are getting shot and action must be taken. . . . ” [235]

In the midst of all this attendant publicity that for a while brought full houses to his play, Scotty was arrested around 24 March by order of the San Bernardino sheriff; he was released later that night on a writ of habeas corpus, his bail of $500 having been raised by Walter Campbell of the Grand Opera House. Seemingly true to the profile presented in the News commenting that “He [Scott] occupies the cheapest room in the Hotel Portland, drinks nickel beer, and leaves no tips!,” [236] after release from jail this time Scotty asked the crowd in attendance “to have a drink. Every body had visions of wine and popping of corks, but Scotty announced it was a case of steam beer or nothing.” [237]

Scotty was arrested again two days later and again released on bail, and then on 7 April 1906 Scott pleaded not guilty to two counts of assault with a deadly weapon. Out again on $2,000 bail, more bad luck was awaiting him in the form of a $152,000 damage suit filed by his brother Warner, now out of the hospital, in Los Angeles Superior Court against Walter and Bill Scott, Bill Keys, A.Y. Pearl, and a “John Doe.” Three days later Keys was arrested at Ballarat, and, also pleading not guilty to the two charges against him, was summarily slapped in jail. Luckily for Scotty, Keys kept silent on the whole matter.

On 13 April, for the fourth time in under three weeks, Scotty was arrested; this time A.Y. Pearl and Bill Scott were also taken into custody. All ended up in the San Bernardino County jail. Out again through habeas corpus proceedings the next day, Scott rejoined his acting troupe. Then, on 27 April, only four days before the preliminary hearing on the case was to start, all charges were dismissed by the San Bernardino County Justice at the request of the District Attorney. To the disappointment of many of Scott’s detractors, but true to the luck that seemed to always rescue him from tight places, a jurisdictional problem had arisen over the fact that the scene of the shooting was actually in Inyo County, which alone had jurisdiction to prosecute the case. Because Inyo County authorities seemed loathe to proceed, all prisoners were released from custody and the final act of the long, drawn-out affair seemed over.

One newspaper article published soon after Scotty’s death (besides stating erroneously that one of the “outlaws” in the fracas had been Bill Scott) charged that Scotty himself moved the surveyor’s post marking the Inyo-San Bernardino County line. [238] This seems to be borne out by Scotty’s own version of the whole affair, which of course pursues the theory that outlaws were trying to get title to his “claims” by permanently removing him from the scene. After several supposed attempts on his life (this most recent encounter not the only one that had taken place in Wingate Pass) from which he always recovered.

Our gang, including my brother Warner, who was working for me and spying for the other crowd, came into Death Valley through San Bernardino County. The two ‘frictions’ met in Wingate Pass. They thought we was the Apache gang. Somebody began to shoot.

I said to Johnson, ‘Get back where the bullets are thickest.’ That was in the ammunition wagon.

I knew something was wrong. When I hollered, ‘Quit shooting!’ things quieted down. The other gang disappeared. We look around and find Warner has been shot in the leg. The same bullet has gone around and lodged in his shoulder. Johnson took eighteen stitches in it. We hauled Warner a hundred miles to a doctor. Had him in a buckboard. Made it in ten hours.

At this time I had a show troop. While it’s playing in San Francisco, I am arrested. I get out on a two-thousand-dollar bond.

Later I was re-arrested, and this time the bond is five thousand, but between the two arrests, I’ve had time to get things fixed. You remember, the fight took place in San Bernardino County, and i don’t want to be tried there.

I decide I’ll move the county boundary monument. When I was a boy, I’d been roustabout for the crew. that surveyed that part of the country, so I know it like a book. I go back and move the pile of rock six miles over into San Bernardino County. That puts the shooting into Inyo County.

The trial starts in San Bernardino. I say, ‘If you investigate, I think you’ll find this affair occurred in Inyo and that this court has no jurisdiction.’ The trial stopped. They investigated. Sure enough, they found the boundary marker. According to the way the line ran, the battle occurred over the line in Inyo County.

Inyo County wasn’t interested. The case was dismissed. [239]

The true nature of the whole affair was later revealed by Bill Keys who admitted before his death that he and a companion (possibly the teamster Jack Brody, although according to Keys it was an Indian named Bob Belt) had faked the ambush at Scotty’s behest. The shooting of Warner had been accidental, his partner being too drunk to aim his gun properly.[240]

Warner Scott dropped his damage suit against his brother on condition that he assume the medical bill of over $1,000 owed to a Dr. C.W. Lawton of Los Angeles. Scott agreed and then promptly left the city. Lawton obtained a judgement against Scotty, but the latter proceeded to ignore it, having no tangible assets anyway.

During the next few years, Scott still had some associations with Wingate Pass, a notice being found that in 1908 he interested Al D. Meyers of Goldfield and a couple of associates in a strike made there. Notwithstanding Scott’s earlier famous experience, the men outfitted in Barstow and accompanied him to inspect the property. There is no evidence that they encountered any difficulties, though nothing further was heard of the outcome of the proposition. Bill Keys was also mining for lead ore in Wingate Pass in 1908, in partnership with Death Valley Slim. [241]

Six years after the Wingate Pass incident, however, on 20 June 1912, the past caught up with Walter Scott, and in a rather spectacular trial in a Los Angeles courtroom, Scotty was forced to acknowledge a multitude of sins. In order to secure his release from jail where he had been confined for contempt of court for not paying the doctor’s bill for his brother Warner’s medical care, Scotty was forced to confess to the shams involved in the ambush in Wingate Pass, in the big rolls of money he always carried (which he confessed were “upholstered with $1 bills”), and in the reports concerning the vast amounts of money he was reputed to have received from the Death Valley Scotty Gold Mining and Development Company. He had, he continued, never located a mine or owned one, and was completely at the mercy of mining promoters and schemers who profited from the advertising his various stunts provided for them. Exposed as a fraud and a cheat, Scott was returned to jail pending further investigation by the District Attorney’s office–a long-awaited and seemingly conclusive finale to the strange affair known as the “Battle” of Wingate Pass. [242]

235. Los Angeles Evening News, 19 March 1906, quoted in Johnston, Death Valley Scotty, p. 68.

236. Los Angeles Evening News, no date, quoted in Johnston, Death Valley Scotty, p. 70.

237. Inyo Independent, 30 March 1906.

238. Ibid., 12 February 1954.

239. Eleanor Jordan Houston, Death Valley Scotty Told Me (Louisville: The Franklin Press, 1954), pp. 72-73.

240. Johnston, Death Valley Scotty, pp. 76-77; L. Burr Belden, “The Battle of Wingate Pass,” Westways (November 1956), p. 8.

241. Rhyolite Herald, 10 June, 30 September 1908.

242. Inyo Register, 20 June 1912.