Adapted from Watch Dogs of the San Bernardino Valley

San Bernardino County Museum Association – Winter 1970

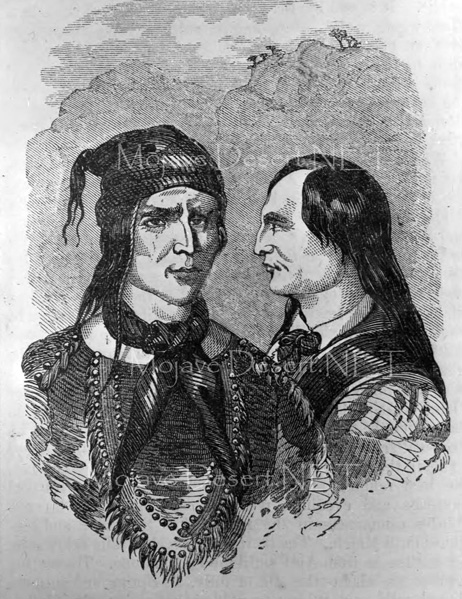

Foremost among the unsung heroes of San Bernardino County during its formative years is Chief Juan Antonio of the Cahuilla tribe. Records speak of this “Watch dog of the Valley” as early as 1844. As an enforcer of the laws and protector of the Valley, he had no peer, and to him, more than anyone else, the towns of San Bernardino and Redlands owe their survival in those early years.

Juan’s birthplace is recorded as having been in San Timoteo in 1873 as closely as we can tell. Undoubtedly, Juan had been raised with a knowledge about the white man and his ways, for long before 1835 the Cahuillas and Serranos of this region had been partially Christianized, hence Juan had been subjected to the thinking and actions of the Spanish before we hear of him in the historical records.

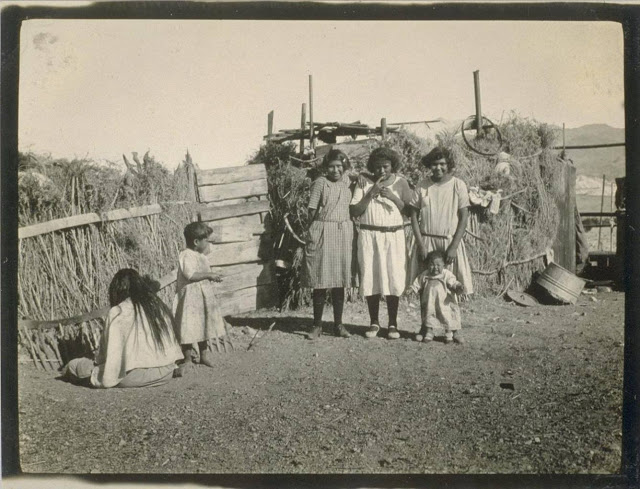

Christian teaching seem to have had little effect in Juan’s personal life, or the lives of the Cahuillas as a tribe, for early records time and time again refer to their returning to untamed savages. As a group the Cahuillas were fierce and loved the sting of battle, as their name brings out. (Cahuilla, Master, or The Great Nation.) The Cahuillas were short of stature and almost black in complexion.

Being from such an aggressive tribe and realizing what was expected from the chiefs of other tribes at that time, one can only assume that Juan Antonio was not an exception to the rule and that he no doubt also won recognition and respect the hard way.

The first time the records speak of Juan Antonio in San Bernardino history came at a time of crisis for the Lugo family. Neophyte Indians of the Valley had joined in with their savage brothers from the desert and were raiding the ranchos of the region. Protection and aid during those years was hard to come by.

The Lugos had previously made an agreement with the Trujillo family whereby they turned over the Politana area for aid in stopping such raids.

Juan Bandini, who was also looking for the same kind of protection, offered the Truillos a better deal in the “Bandini Donation,” hence the Trujillos pulled up stakes and moved to their new home.

Just how the Lugos and Antonio met and agreed on a working agreement is not stated however.

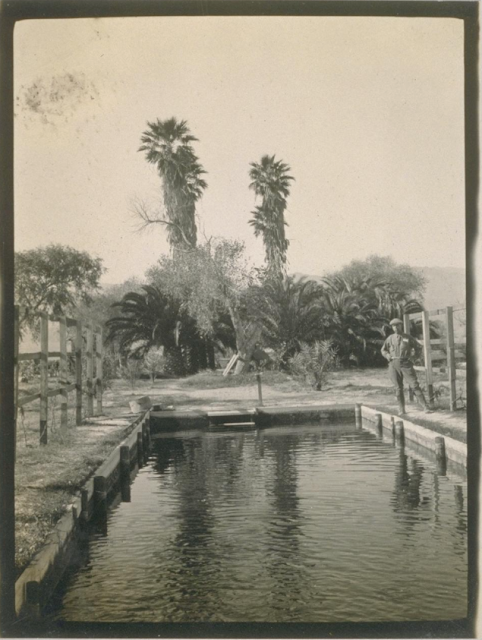

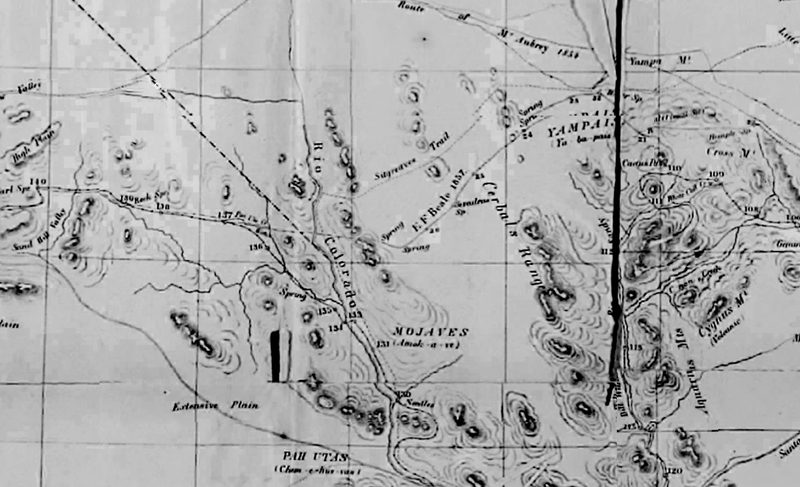

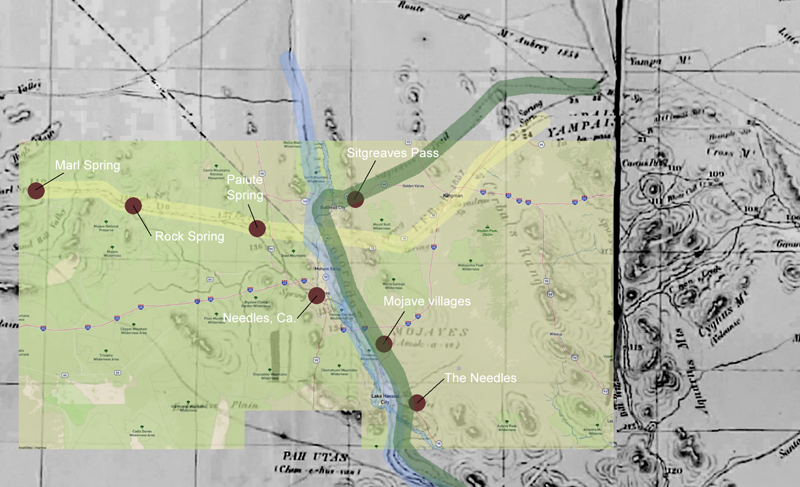

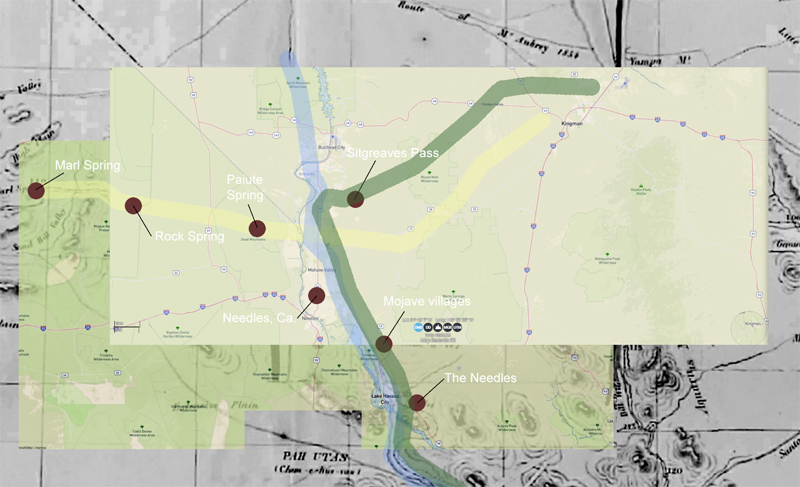

“After the departure of the settlers from Politana, the Lugos placed Juan Antonio, the Cahuilla chieftain, on the vacated tract, and he and his warriors rendered faithful service in protecting the lugo stock. In a letter Antonio Maria wrote to a friend in Los Angeles in February, 1844, he said that very day Cahuillas were fighting near San Bernardino with savage Indians whom he was expecting to attack the rancho at any moment, presumably to run off his livestock. This encounter may have marked the coming into the Valley of Juan Antonio and his followers, and their behavior then may have suggested the idea of enlisting their aid in combating Paiute and Mohave intruders regularly.

“Juan Antonio did not occupy the adobes on the bluff, but located his rancheria on the ridge near the headquarters of Vincente Lugo, and near the settlement and near the settlement of unconverted Indians to whom Antonio Maria had referred to in his petition of four years before. The abandoned cabins became mere landmarks. In 1851, when the Los Angeles County Court of Sessions defined the public road from San Gabriel to San Bernardino, it described it as running “by the old pueblo of the New Mexicans, known as Apolitan.” The settlement seems even then to have been so nearly forgotten that the name Apolitan was being applied to Vicente Lugos rodeo grounds and to the rancheria on the ridge.”

Thus began a long and close friendship that was to last until the end of the Mexican period in the Valley. Right up until the end, Juan Antonio’s loyalty to his employer never wavered. It was during the Mexican War that Antonio showed his faith in the Lugos. While other Indian groups were quick to desert their sponsors and join with what looked like the sure winners, Antonio held fast to his bargain.

“Helen Hunt Jackson says that he received the title of ‘General’ from General Kearney during the Mexican War and never appeared among the whites without some signs of a military costume about him.”

The Luiseno Indians of the Pauma Valley, seeing the Mexican troops defeated by the Americans, sensed an opportunity to impress the new rulers by joining with them. Eleven Mexican troopers were massacred by the Luiseno tribe in the most horrible way. Vengeance, however, has a way of striking back.

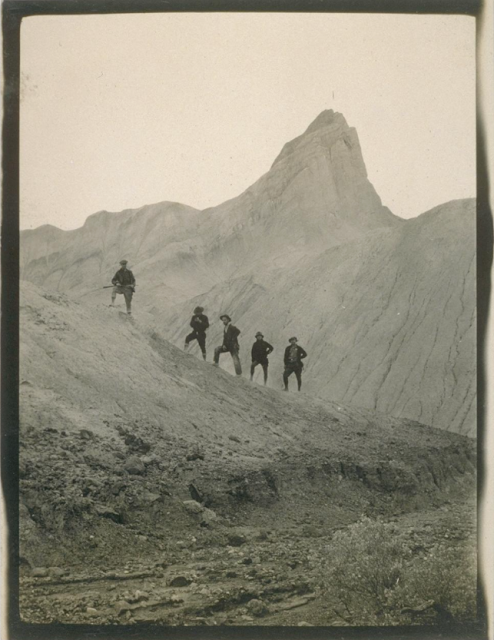

“General Flores was heading the revolting Californians in Los Angeles at this time, and when the news of the killing of Pico’s troopers reached him, he delegated Jose del Carmen Lugo to go in pursuit of the assassins. Lugo left Los Angeles with fifteen men, and recruited along the way until he had twenty-one, five from San Bernardino. Juan Antonio went with fifty of his fighting men. By a ruse, Lugo succeeded in catching the Luisenos in an ambush, killed many of them and captured others. The captives were placed in the charge of Juan Antonio, who promptly put them to death. When reproached by Lugo for his needles cruelty, he remarked coolly that if they had caught him they would have roasted him alive. He added that Lugo was captain of white men, while he was captain of Indians, and there was a difference. This wreaking vengeance on the Luisenos by Lugo’s party was regarded as a noteworthy exploit.

The signing of the articles of capitulation at Cahuenga brought very little change in the established pattern of life in the area. Cattle, horses, and sheep were the economic basis of the ranchos, hence records continue to record raids into the Valley and the use of Chief Antonio’s Cahuillas in meeting such forays with force.

“San Bernardino, February 3, 1848. … I write to inform you of what occurred today. We set out for the mountains of the Agua Caliente in pursuit of the Indians who stole the horses, and Juan Antonio and his people fought with them and killed six Indians, two of them captains.”

The Americans proved to be more aggressive than had the Spanish authorities and in most areas the Indians were quickly brought into line by a strong show of power. San Bernardino, however, was still somewhat of a frontier area and the Indian problem persisted for some time.

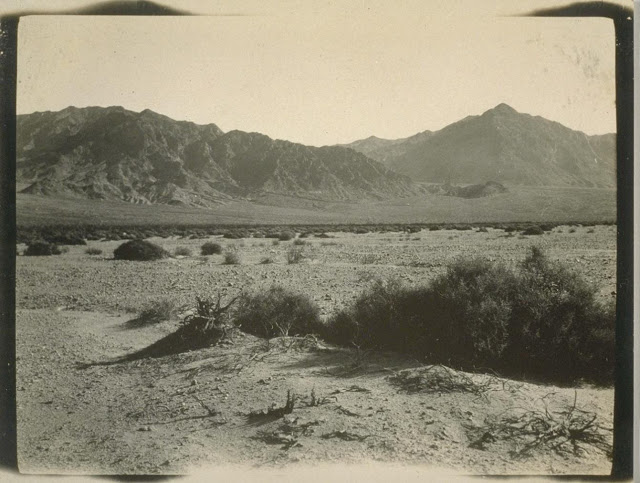

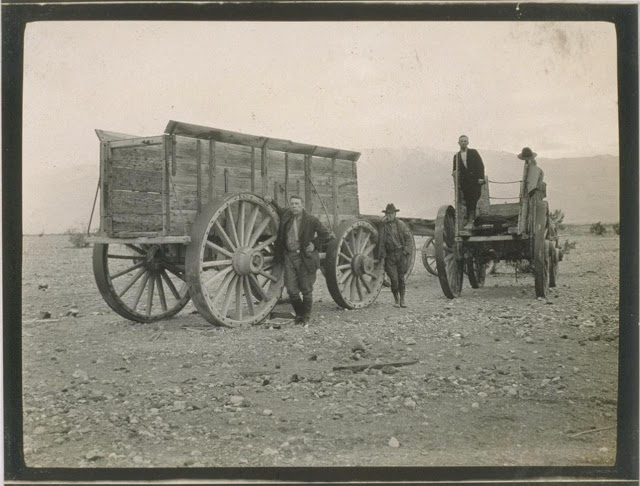

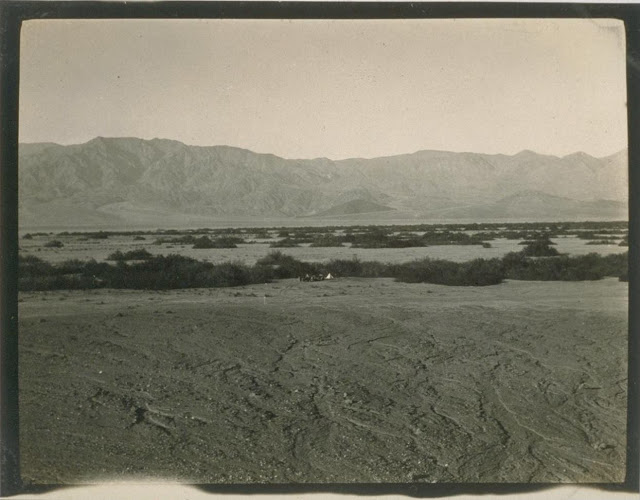

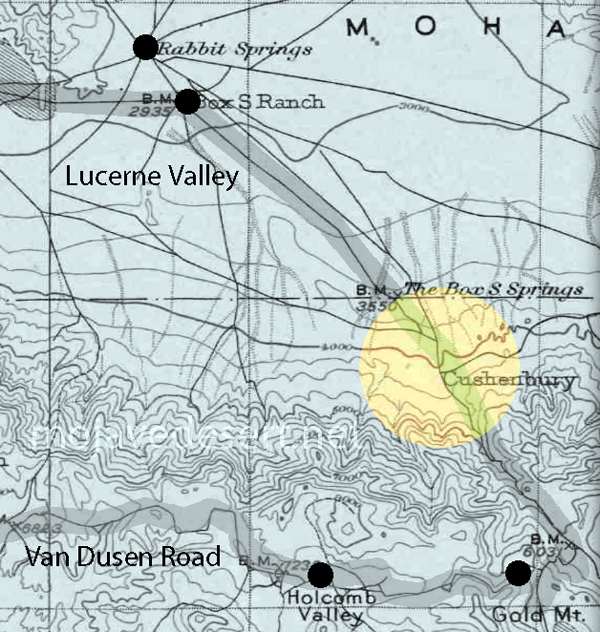

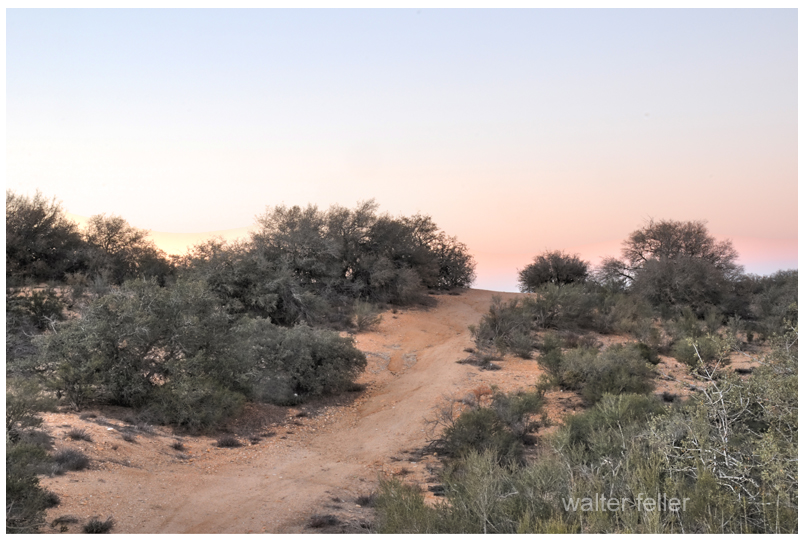

“During the winter of 1850-51, Wak’s (Walkara) Utah Indians had been particularly active, harrying the ranchos in the San Bernardino Valley as far west as the present towns of Pomona, Claremont and Azusa. So great was the annoyance they caused that a large party of Californians and Americans, supplied with firearms from the United States military post at Chino, went in pursuit of them. General J. H. Bean, commander of the militia in Southern California, finally recommended that a company of fifty volunteer rangers be authorized by General McDougal as a protection for these frontier regions. The company was organized and stationed in Cajon Pass. Later, because of persistent bad weather at that point, General Bean moved it near Apolitan on Lugo’s ranch, and established Camp Dolores, not far from the present San Bernardino Valley Junior College grounds.

“Before the rangers had gone to the Cajon, the Utahs had driven off a large band of gentle horses belonging to Jose Maria Lugo, of Jumba, and he and his neighbors, accompanied by Juan Antonio, and his warriors, pursed the robbers into the desert. On the Mojave River they received a volley of rifle balls from an ambuscade, and one of the white men of the party was killed.”

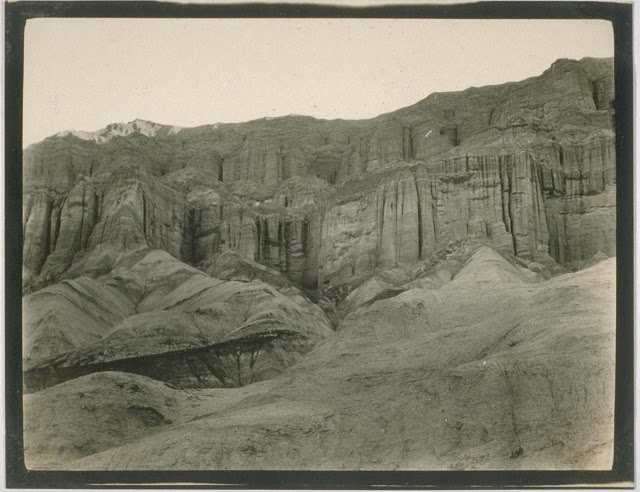

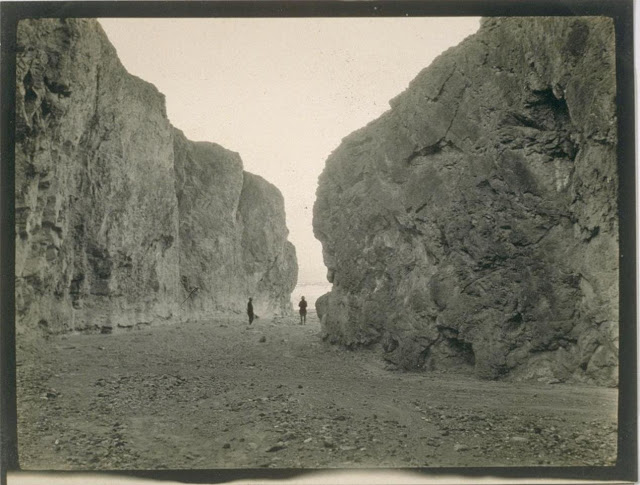

On their way back from the ambush that had taken place during the pursuit of Walkara, two of Jose Maria Lugo’s sons, accompanied by two others of the original group, ran into a couple of men encamped in the Cajon. After ascertaining their presence in the valley the young men returned home. A few days later, another party going through the pass found the wagon and the bodies of the two white men who had been encamped in the Cajon. The two young Lugo boys were blamed for their murders. The case was transferred to Los Angeles. Here, an American soldier, John Irving, accompanied by a number of Sidney Ducks and other ex-soldiers, offered to tear down the jail and free the two Lugo boys for $5000. The grand old man refused, preferring to depend on his lawyer and justice. This infuriated Irving and he threatened to kill both the Lugo boys if they were set free. To make a long story short, the Lugo boys were set free. Irving, in the meantime, swore revenge on the Lugo family and headed with his men to San Bernardino. He got mixed up on his way, however, and stayed at the Rubidoux Rancho. In the meanwhile, the Lugos had been warned. The “Watch Dog” was waiting and a running battle took place across the Redlands plains to the Sepulveda home in Yucaipa. From here Irving and his men made it to San Timeteo Canyon only to be bottled up by Juan Antonio and his braves. In the ensuing fight, eleven of the twelve man army, including Irving, were killed.