L. Burr Belden

San Bernardino Sun-Telegram September 6, 1959

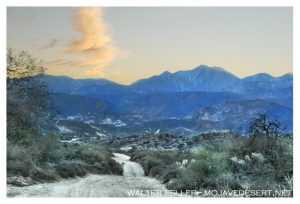

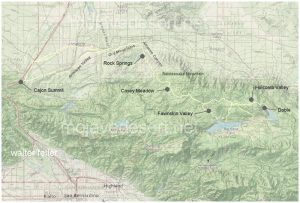

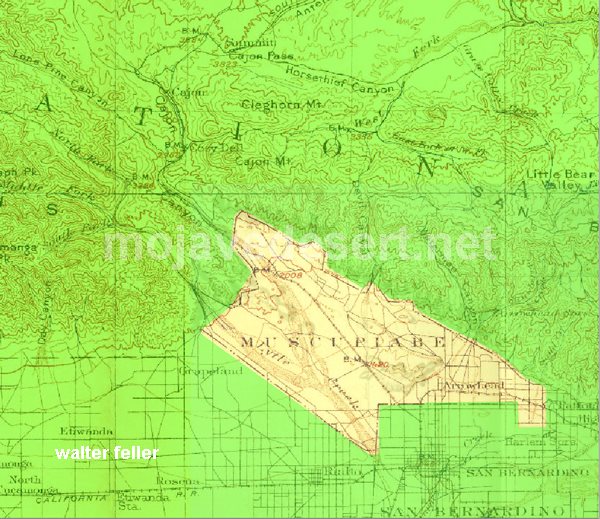

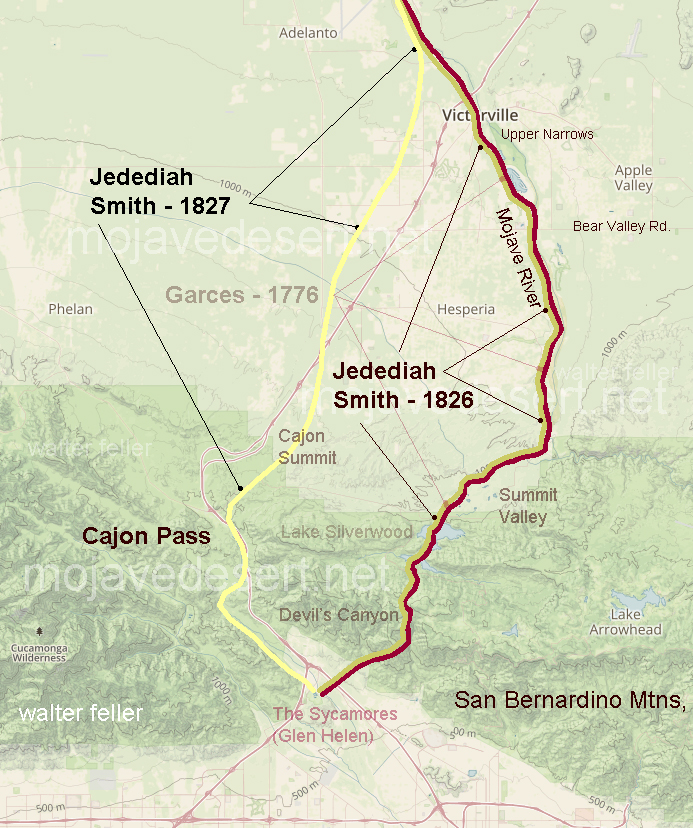

In 1861 the county of San Bernardino contracted with John Brown to build a toll road through the Cajon Pass from Devore to Cajon Summit. That would do fine to get wagons and freight between San Bernardino and the Mojave Desert. At the same time the county also approved a subscription road to be built by Jed Van Dusen from near the summit through the mountains so equipment and supplies could be freighted to the mines in Holcomb Valley.

History in the Making

Mountain Road Cost Miners $2,000 in Gold

Back in the early 1860s the gold rich but food poor miners of Holcomb Valley decided the number one need for their mountain metropolis was a road. in typical pioneer fashion instead of looking to San Bernardino, Sacramento or Washington these miners resolved to build the road.

At the time supplies for Holcomb Valley were brought up by way of a packed train trail up Santa Ana Canyon from the San Bernardino Valley and thence to Holcomb Valley by trails threading either Polique or Van Dusen Canyons. these trails served for burros, mules or horses but the only way to get a wagon to the gold mines was to take it apart and load its pieces on pack animals.

Toll Road up Cajon

The Holcomb Valley mines were reputedly among the richest in California. Free gold, as the placers were known, was becoming hard to obtain in quantities up in the worked over streams of the Mother Lode and accordingly thousands of footloose miners poured into Holcomb Valley making an increasingly heavy strain on the thin supply line.

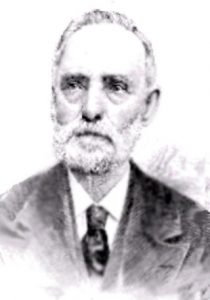

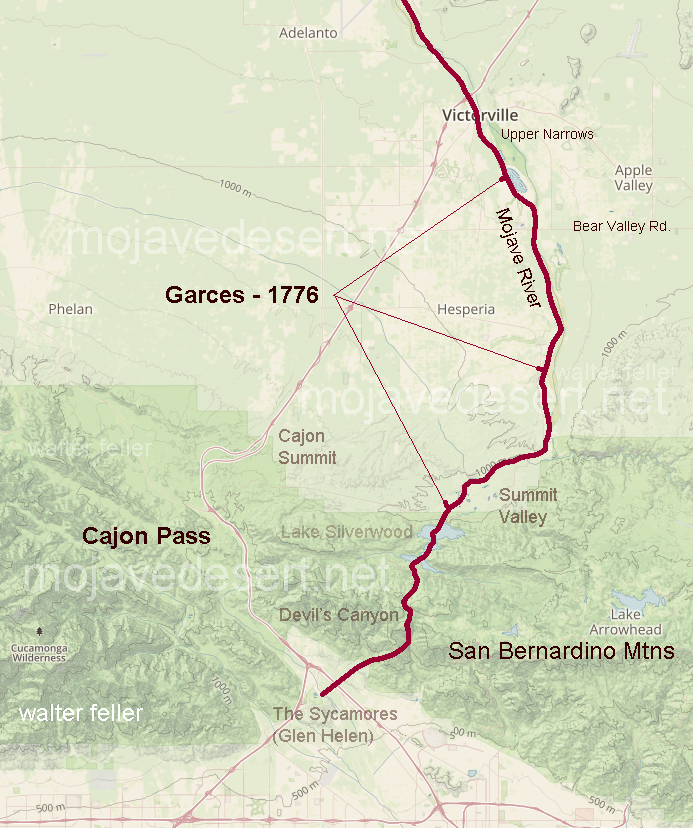

Down in San Bernardino John Brown Sr. a resourceful Rocky Mountain man, who was one of the leaders in the settlement both during and subsequent to the Mormon regime, had an experienced eye for trade routes. Brown was probably one of the first to vision San Bernardino as a trade center due to its central location and proximity of favorable mountain gateways.

Brown saw that San Bernardino could obtain an even better share of overland travel with better roads. Accordingly he planned to make the Cajon Pass gateway the preferable way east. He applied to the Board of Supervisors and was granted a toll road franchise. His road utilized the East Cajon route which he improved so it could accommodate wagons. Then Brown went farther and started a ferry over the Colorado River at Fort Mohave.

Builder Paid $2,000

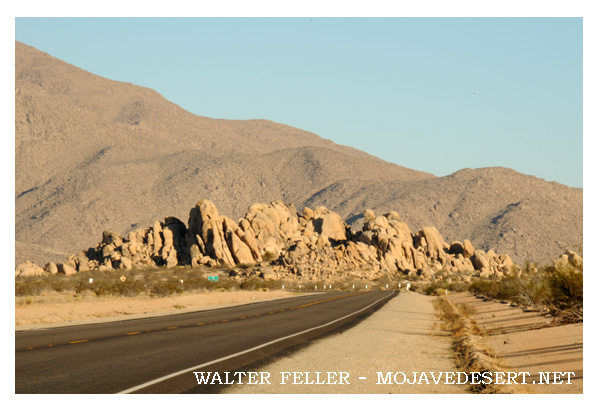

The Brown Road diverted Holcomb Valley traffic away from the Santa Ana trail. A new trail was blazed down Holcomb Creek, Willow Creek and Arrastre Creek to reach the Mojave Desert floor in the vicinity of Deadman Point. From Deadman Point it was an easy open path to Brown’s road.

Miners and supply men who used the new trail saw that it could be widened to accommodate wagons. The usual method of making a road would have been for the Holcomb Valley miners to turn out with their picks and shovels, but that meant leaving their claims just when water was high enough for gold washing. Accordingly a person of $2,000 in gold dust was raised and Jed Van Dusen, the camp blacksmith, was hired to build the road. He did just that. Van Dusen was a resourceful fellow. He had assembled a wagon from parts brought up to Holcomb Valley by pack train. In between running his smithy he had some good claims he worked in the canyon that has been given his name. Van Dusen’s chief claim to fame, however, was neither his skill as a road builder, blacksmith or miner. it rested on the fact he was father of a very pretty little girl named Belle.

Daughter Honored

When the miners cast about for a name for their town in Holcomb Valley they found W. F. (Billy) Holcomb reluctant to have it named for him. Then someone had an idea. Why not name the camp for Jed Van Dusen’s little girl? So Belleville became the name of the big roaring mining camp that had almost as many residents as the rest of the county.

For a dozen years or so the Van Dusen built road carried the heaviest traffic in the county. The travel to the mines, of course, was a great help to the Brown tollway. Heavy machinery needed for quartz mining was hauled over the road as gold veined ledges were discovered. The latter included two of the most famous gold mines San Bernardino County history, E. J. (Lucky) Baldwin’s Gold Hill property and Richard Garvey’s Greenlead.

During Civil War days the Van Dusen – built road carried a strange assortment of passengers and cargo. Liquors for Greek George’s notorious saloons and dance halls, staple goods, the inevitable blasting powder and large bullion shipments. Strangest of all travelers, however, was a ragged troop of filibusters recruited in Visalia who called themselves Confederate calvarymen and commanded by Mariposa County’s stormy Assemblyman Dan Showalter. Showalter and his motley horsemen were trying to reach southern lines in Texas but a few weeks later ran into California volunteers near Warner’s Ranch and were taken prisoner.

This was the same Showalter who had recently slain San Bernardino County’s Assemblyman Charles Piercy in a duel at San Rafael. The duel was fought with rifles at 40 paces. First shots of both antagonists went wild and Showalter allegedly jumped the gun and shot the second time at the count of two, killing Piercy. Showalter was a fugitive when he was in Holcomb Valley but secessionist sentiment plus that of roughs who wanted no government at all served to protect the fact it was San Bernardino County’s legislator he had slain.

The roughs around Belleville ran things with a high hand, at least until Greek George fell mortally wounded from the knife of ” Charlie the Chink” in the drunken aftermath of a Fourth of July celebration. In a reminiscent account written 35 years later Billy Holcomb told of that fatal July 4 and of George’s killing three men before his fatal combat with the celestial.

It was members of George’s gang, left more or less leaderless, who held up an outgoing stagecoach and relieved the Wells Fargo messenger of $60,000. It was the disgusted miners, anxious to drive out the roughs, who pursued the highway men and killed them all. The last bandit was slain a bit too quick for he died while trying to tell where the $60,000 was hidden. As far as is known it has never been found, a sizable cache of gold bars that has lured treasure seekers unsuccessfully for something like 90 years.

Baldwin Garvey Feud

The Van Dusen Road carried the ballot boxes in the weird election when Belleville tried to become county seat, and probably succeeded in polling a countrywide majority but lost on the official count by the “accident” of a Belleville precinct’s box being lost in a bonfire down in San Bernardino.

After the richer placer deposits had been worked Belleville and upstream Beardstown dwindled in size. The emphasis’s one to hard rock mining which required less men more capital and tools. In the hard rock field the giant was Baldwin, who at one time was running a 40- stamp mill at Gold Hill and the operation was supporting a good-sized town, the town of Doble.

Next in size to Baldwin’s operation were those of Garvey. Garvey had owned Gold Hill at one time and reportedly sold it to Baldwin for $200,000. The Garvey family always contended that Baldwin took a bill of sale for the mine but neglected to pay the Irish-born Garvey all the promised money. Garvey trusted his supposed friend.

Garvey held onto the Greenlead, which is almost at the side of the Van Dusen Road in lower Holcomb Valley. When hard times depressed Los Angeles real estate Garvey found he owed $300,000 on the land no longer worth the amount of the mortgages. Three shifts worked the Greenlead and Garvey paid all but $90,000 of the $300,000 debt. The family held onto the Greenlead. It had been leased, sold and worked from time to time. The new owner from Sherman Oaks was on the property a year ago with plans for reopening the long tunnels where there is still said to be quantities of ore rich enough to pay for mining even under current costs.

Long Cattle Drives

In the wake of the minors cattlemen moved into the San Bernardino Mountains. The old road to Holcomb Valley saw huge drives in both spring and fall as cattle were moved from desert ranges to the mountains and back again.

When the first dam was built at Bear Valley in the 1880s A. E. Taylor hauled supplies over the old road, then completed and used the road up Cushenbury direct to Bear Valley. Advent of the Cushenbury gateway, now Highway 18, and the later Mill Creek and crest routes serve to diminish the importance of the old route but it was not closed.

Halfway down to the desert, at the well-known landmark of Coxey’s Ranch, the Forest Service had one of its early ranger stations. It was one of the picturesque log cabin structures typical of such stations 40 years ago. A search for the station earlier this summer disclosed that he had reverted to the status of a guard station and that two or three years ago it was burned when a gasoline lantern or stove exploded. The old corral remains Coxey’s. Today’s guards camp out and have telephone service.

The old road is a popular one with Forest visitors who like to get away from the pavement and camp out. There are public grounds at Horse Springs, Big Pine Flats, and that Hannah Flats. Numerous Springs make the route a well watered one that it is no place for a pavement driver with a low center car.

- end